Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

Discover the Hotel Warner with its exciting past as a grand and deluxe Art Deco movie theatre.

The Warner Theater: Showplace of Chester County

Discover the amazing history of the Hotel Warner back when it operated as the state-of-the-art Warner Theater.

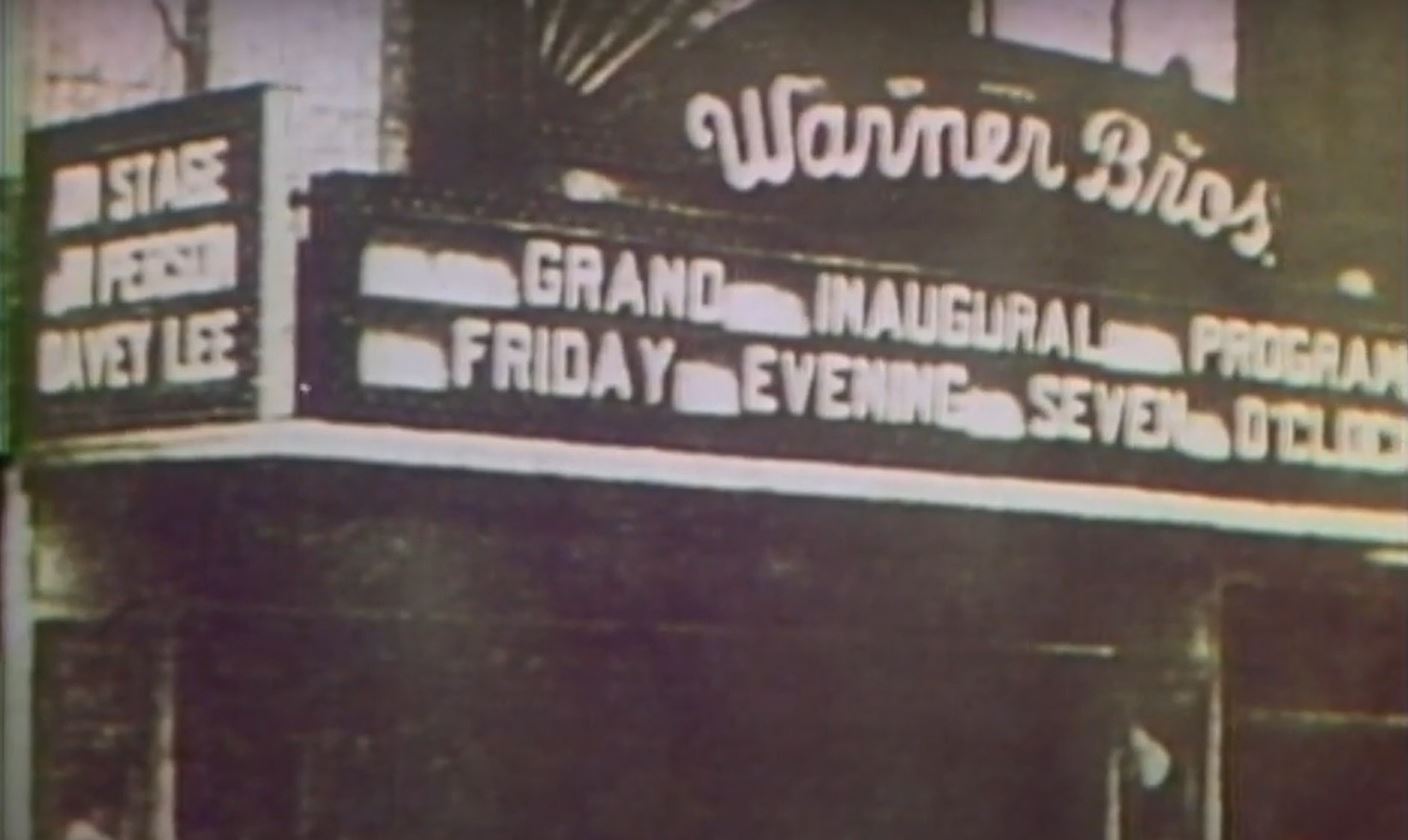

WATCH NOWA member of Historic Hotels of America since 2016, Hotel Warner has been one of West Chester’s most celebrated historical landmarks. In fact, this spectacular historic hotel is among the few to feature a listing in the U.S. National Register of Historic Places. But the Hotel Warner has not always been a spectacular holiday destination. On the contrary, the building once served as the magnificent Warner Theater for generations. West Chester itself was selected by Warner Bros. Pictures as the location for an opulent 1,650-seat venue. The studio subsequently built the structure at the southwest corner of High and Chestnut Streets, replacing a horse stable and corral that had previously occupied the space. It was designed by the firm Rapp & Rapp of Chicago, then regarded as one of the leading designers of early 20th century movie palaces. (They designed over 400 theaters, including the Majestic Theater in Dubuque, Iowa (1910), the Chicago Theater (1921), Bismarck Hotel and Theater (1926), Oriental Theater in Chicago (1926), and the Paramount Theaters in New York (1926) and Aurora (1931).) Their work on the Warner Theater—also known as the “High Street Theater” or the "Showplace of Chester County”—included the theater, restaurant, and a series of small stores. The building even had a two-story foyer and a three-story tower that supported the marquee. The brilliant Warner Theater finally debuted in 1930 with a showing of The Life of the Party, an all-talking Technicolor comedy starring Winnie Lightner. Warner Bros. child star Davey Lee even made a personal appearance on opening night, who sang and danced on stage.

When its days as a movie theater ended during the 1970s, developers renovated the Warner Theater to host live entertainment. Nevertheless, the theater eventually closed in 1984, with Woody Allen’s Broadway play Danny Rose running as the final show. Efforts to preserve the building were ultimately insufficient, and the auditorium’s subsequent demolition took place two years later. Only the façade and lobby areas remained untouched, becoming local offices for the Philadelphia Inquirer for some time thereafter. Thankfully, the erstwhile movie theater was saved from further deterioration after Brian McFadden of The McFadden Group acquired the site in the 21st century. Working alongside Bernardon Haber Holloway Architects of Kennett Square, McFadden quickly set about renovating the structure back to its former glory. Together, the two endeavored greatly to restore the building, turning it into a brilliant boutique hotel called the “Hotel Warner” in the process. Due to their hard work, the original theater lobby and its ornate period staircase became a gorgeous hotel lobby, while a new tower behind the theater housed many luxurious guestrooms. Brian McFadden himself specifically worked with the architectures to ensure the architecture of the new tower complemented the historic design. After months of continuous construction, the new business finally opened for the first time in 2012. Centrally located to countless restaurants, sidewalk cafes, brew pubs, and eclectic shops, Hotel Warner is the only hotel in West Chester’s historic downtown. Visitors can enjoy a stroll through the historic streets and discover the rich architecture and vibrant past of this nationally acclaimed neighborhood.

-

About the Location +

Despite holding a separate listing in the U.S. National Register of Historic Places, the Hotel Warner is also a contributing structure within the federally recognized West Chester Downtown Historic District. The district itself constitutes the historic core of West Chester, which has existed as an independent borough since the time of the American Revolution. West Chester was born out of an earlier community called “Turk’s Head” that had formed around a rustic country tavern of the same name. Its two main thoroughfares—the future Gay and High Streets—attracted many travelers from Philadelphia, making it an incredibly busy crossroads. In fact, a schoolhouse in the village even served as a temporary field hospital for wounded American soldiers after the Battle of Brandywine in 1777. Its future changed dramatically, though, when the Pennsylvania General Assembly commissioned the development of a county courthouse in the middle of Turk’s Head a decade later. Its newfound political importance even led to its eventual incorporation as the borough of “West Chester” by the end of the century. West Chester grew gradually until the outbreak of the American Civil War, rising from just 374 residents in the 1790s, to well over 4,700 by 1860. The proliferation of various state-sponsored roads helped this growth considerably, although it would not be until the arrival of the railroads in the 1830s that West Chester experienced a true population boom.

But the coming of the railroads also heralded the emergence of West Chester’s commercialized economy, with the Everhart Building opening as the first office complex in town. Soon enough, more industries appeared in West Chester, including watchmaking, pottery manufacturing, and ironworking. Nurseries became ubiquitous in the borough, too. The most successful were Morris Nursery, Kift Nursery, and Hoopes Brothers and Thomas, which employed several hundred people by the height of the Gilded Age. And as the town diversified in the 19th century, so too did its landscape. Several brilliant Greek Revival structures quickly defined the emerging urban landscape, epitomized by the new county courthouse that the great Thomas U. Walter constructed in 1846. West Chester had even started entertaining various universities within its borders, including the West Chester Academy—the predecessor to the prestigious West Chester University. West Chester became something of a hotbed for anti-slavery sentiment around the same time, as many prominent citizens began to transform their homes into stations for the Underground Railroad. Dozens of influential abolitionists also spoke before the community at its Horticultural Hall, including Horace Greeley, Wendell Phillips, and William Llyod Garrison. The structure even hosted prominent women’s suffragists like Sojourner Truth and Lucrecia Mott (both of whom were also abolitionists) and served as the meeting place for the First Women’s Rights Convention in Pennsylvania.

By the dawn of the 20th century, many people in the commonwealth referred to West Chester as the “Athens of Pennsylvania.” The identity nonetheless started to disappear during the decades that followed, as West Chester was transformed into a suburb of Philadelphia. Factories were soon a common sight throughout the borough, with some the largest being the Darlington Steel Works and the Sharples Separator Works. West Chester also became the headquarters for the Chester County Mushroom Laboratories in World War II, which successfully developed a way in which to mass produce penicillin. But the years that followed the war saw West Chester enter a steady decline as the economy shifted from manufacturing operations to retail. Nevertheless, the community experienced a renaissance in the 21st century, with many local leaders sponsored the creation of the Business Improvement District in 2000. The partnership has proved to be very fruitful, as it has seen West Chester’s rebirth as a revered cultural heritage destination. Revitalized boutique storefronts, restaurants, and apartment buildings now reside at the center of West Chester, as do a number of fantastic historical structures that the borough has painstakingly renovated. The community is also close to many fascinating cultural attractions, too, such as Valley Forge National Historical Park, Longwood Gardens, and the many brilliant landmarks located in nearby Philadelphia.

-

About the Architecture +

Warner Bros. Pictures endeavored to create one of the most ornate movie palaces in downtown West Chester when it began constructing the Warner Theater at the height of the Roaring Twenties. Interestingly, Warner Bros. Pictures had not actually conceived of the plans. In reality, another company called the “Stanley Corporation of America” had originally sought to create the future Warner Theater. Founded in Philadelphia, the Stanley Corporation was a conglomerate that had obtained the rights to operate some 200 movie theaters throughout the commonwealth. As such, it was Stanley Corporation that had purchased the original plot of land at High and Chestnut Streets and developed the first building plans. In fact, the company was willing to invest more than $700,000 to construct the awe-inspiring structure. But a few weeks later, the ambitious Warner Bros. Pictures bought out the Stanley Corporation of America and adopted the blueprints for the new theater. Rechristening it as the “Warner Theater,” Warner Bros. Pictures immediately set about constructing the building in June, 1929. The work nonetheless continued unabated, even as the Great Depression beset the local community just three months into the project. Many in the community remained thankful that Warner Bros. had not abandoned West Chester, too. As such, countless local residents flocked to the structure when it was finally completed in November, 1930, with some even working a variety of roles. High schoolers were the most common type of employee at the Warner Theater, who served as ushers after completing an intense three-week-long training course.

To design the magnificent structure, Warner Bros. sought the best architectural minds at the time. At first, the company considered hiring architect William H. Lee, before settling on brothers C.W. and George Rapp of Chicago. Through their accomplished architectural firm, Rapp & Rapp, the two men crafted a stunning three-story structure with a brilliant array of Art Deco design elements. The Rapp brothers subsequently built the magnificent building around a steel frame and a solid concrete foundation. The exterior walls featured hollowed tiling, as well as mixture of red brick and cast stone. But the façade’s most outstanding feature was the striking tower that spanned the height of the building, and the illuminated “Warner” sign that it supported. Inside, the building opened to a beautiful lobby defined by a variety of Art Deco motifs, such as numerous chevrons and zigzags. Chromatic paints also spread throughout the lobby, echoing the color palate that characterized the Art Deco movement. Nevertheless, the Rapps took great liberty in drawing inspiration from other sources, too, including ancient Grecian, Asian, Egyptian, and even Mayan civilizations. The lobby’s balcony was one such place where their imaginative creativity was on display, as the designs mimicked cultural aesthetics from both South America and Scandinavia. But theater’s auditorium was the most impressive of all. The space was massive, consisting of some 1,300 seats on the ground floor and another 300 above on a shorter second level. The two brothers installed huge plaster panels draped in heavy rich velvet and coated the exposed areas in gorgeous metallic paints.

Art Deco architecture itself is one of the most famous architectural styles in the world. The form originally emerged from a desire from architects to break with past precedents to find architectural inspiration from historical examples. Instead, professionals within the field aspired to forge their own design principles. More importantly, they hoped that their ideas would better reflect the technological advances of the modern age. As such, historians today often consider Art Deco to be a part of the much wider proliferation of cultural “Modernism” that first appeared at the dawn of the 20th century. Art Deco as a style first became popular in 1922, when Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen submitted the first blueprints to feature the form for contest to develop the headquarters of the Chicago Tribune. While his concepts did not win over the judges, they were widely publicized, nonetheless. Architects in both North America and Europe soon raced to copy his format in their own unique ways, giving birth to modern Art Deco architecture. The international embrace of Art Deco had risen so quickly that it was the central theme to the renowned Exposition des Art Decoratifs in Paris a few years later. Architects the world over fell in love with Art Deco’s sleek, linear appearance defined by a series of sharp setbacks. They also adored its geometric decorations that featured such motifs like chevrons and zigzags. But in spite of the deep admiration people felt toward Art Deco, interest with the style gradually dissipated throughout the mid-20th century. Many examples of Art Deco architecture survive today, with the some of the best located in such places like New York City, Chicago, and Miami Beach.