Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

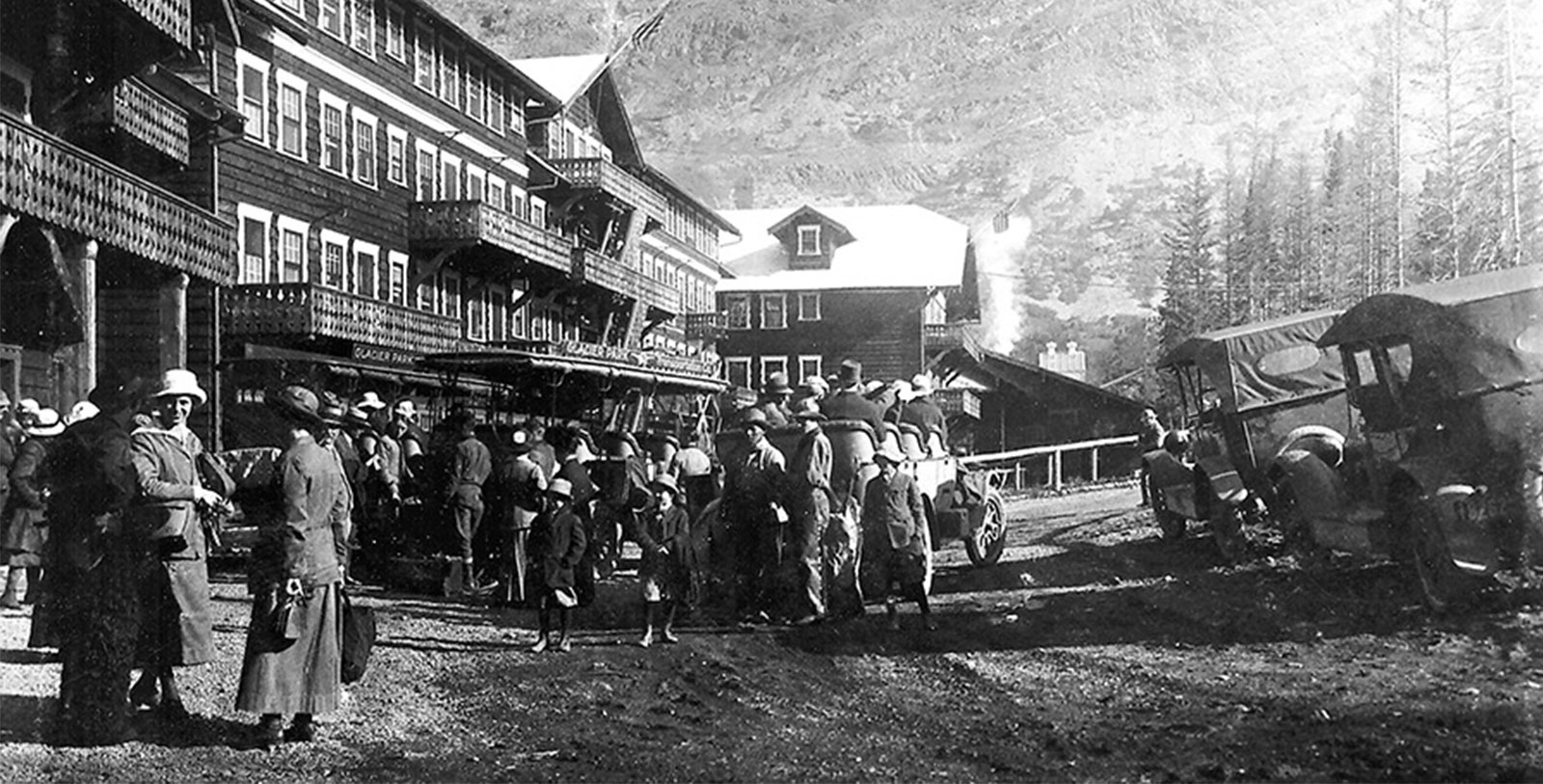

Discover the Many Glacier Hotel with its rustic design and ambiance.

Many Glacier Hotel, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2013, dates back to 1915.

VIEW TIMELINEA U.S. National Historic Landmark, Many Glacier Lodge has stood as a cherished landmark in Glacier National Park for more than a century. Its history is quite extensive, too, harkening back to the park’s very formation! In fact, the person responsible for creating the hotel, Louis W. Hill, played an instrumental role in creating Glacier National Park in the first place! Hill and other conversation-minded advocates had spent decades attempting to push the U.S. Congress to federally protect the region from widespread industrial development. After enduring years of failure, Hill and his allies eventually succeeded when President William Howard Taft finally designated the area to be Glacier National Park in 1910. The federal government and Hill then negotiated a contract to grant the Great Northern Railway the right to serve as the official concessioner. Among the many responsibilities that the company received was the task of opening visitor facilities throughout the area. As president of the Great Northern Railway, Hill personally began developing several hotels across Glacier National Park on behalf of the federal government. His greatest project was the Many Glacier Hotel complex, which he began constructing along the shoreline of the park’s Swiftcurrent Lake on the eve of World War I. Starting first with a number of small, rustic cabins, Hill’s design team then began to build a gorgeous four-story structure that was an engineering marvel. They specifically constructed the entire facility to resemble a collection of Swiss-inspired chalets as part of Hill’s greater attempts to market the park as the “American Alps.” To that end, wood cut from the surrounding forest constituted both the walls of both the chalets and hotel, which workers linked together in a jigsaw pattern. Inside, the spaces displayed a wealth of Swiss architectural details, as well as additional motifs that reflected the heritage of the “Old” American West.

When construction on both the chalets and the hotel concluded in 1915, they quickly emerged as one of the most popular of Great Northern Railway’s destinations in Glacier National Park. The hotel itself became known as “Many Glacier Hotel” and served as the true focal point for the entire complex. (While the Great Northern Railway remained the operator of the hotel, the newly minted National Park Service became the ultimate owner.) Indeed, it was soon entertaining hundreds of guests every month, especially once Glacier National Park’s iconic Going-to-the-Sun Road opened during the 1930s. Many Glacier Hotel had even started hosting several influential figures, including John D. Rockefeller, Groucho Marx, and U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt. This popularity only continued to grow over the following decades, which led to refer to it affectionately as the “Gem of the West.” But despite the love that the Many Glacier Hotel instilled in its guests, the Great Northern Railway gradually came to see it as a financial hindrance. The company thus began seeking out another party to purchase its rights to operate the facility and eventually reached an agreement with the prominent Hummel family of Tucson, Arizona. After operating the hotel for two decades, the Hummels, in turn, agreed to sell its concessioner rights to a subsidiary of the Greyhound Corporation. More recently in 2013, the esteemed Xanterra Travel Collection forged a contract with the National Park Service to become the new concessioner. Under the watch of the Xanterra Travel Collection, Many Glacier Hotel has reached new heights of renown and popularity. It has also masterfully safeguarded the heritage of the complex, too, ensuring that it remains intact for future generations to appreciate. A member of Historic Hotels of America since 2013, Many Glacier Hotel is truly a wonderful place to experience.

-

About the Location +

For millennia, the area that now constitutes the historic Glacier National Park was inhabited by many tribes of Native Americans. While the location served as the home for different people periodically, only the ancestors of a few tribes—notably the Blackfeet and the Flathead—still live nearby today. (Both the Blackfeet and the Flathead began residing in reservations that directly bordered the park in 1855, with the Blackfeet living to the park’s eastern border and the Flathead staying to the west.) Nevertheless, the park remained free from largescale human settlement, which preserved its gorgeous landscape and fascinating ecosystem. Efforts to federally protect the region started emerging in the latter half of the 19th century, especially once industrialization began materializing across much of the western United States. Respected naturalist George Bird Grinnell spearheaded the campaign to safeguard the region’s natural beauty, specifically lobbying the U.S. Congress to pass laws that could protect it. After spending years petitioning Congress, Grinnell received much needed help from Louis W. Hill, president of the Great Northern Railway. In 1891, Hill’s company had led a portion of its rail network through Marias Pass nearby, which split the Continental Divide just south of today’s park boundaries. Recognizing the area’s inherent magnificence and potential for tourism, Hill then joined Grinnell in pushing for the region’s public conservation. As such, Congress eventually turned thousands of acres into an official federal forest preserve in 1897.

However, the designation did not fully conserve the local geography, as commercial mining and lumber operations maintained their local leases. Grinnell and Hill therefore increased their attempts to save the site, hoping to ultimately transform it into a national park. To help win their fight, the two men formed a powerful alliance with the Boone and Crockett Club—an incredibly influential wildlife conservation group that President Theodore Roosevelt had founded several years prior in 1887. Their combined advocacy finally convinced Congress to pass legislation that made the area a national park, which President William Howard Taft then signed into law right before World War I. The bill specifically gave the region the name “Glacier National Park” after the ancient glaciers that resided throughout the mountainous landscape. Glacier National Park quickly then became one of the most popular natural landmarks in the whole country, with many tourists visiting via the Great Northern Railway. The railway had also become the park's official concessioner, prompting Hill and his contemporaries to host the throngs of guests now arriving in their train cars. Hill subsequently commissioned the construction of numerous hostelries that resembled Swiss Chalets as part of a grander marketing strategy that presented the region as America’s “Switzerland.” (While Lake McDonald Lodge originally opened around the same time and displayed the same architecture, it was not built by Hill’s team.)

In 1916, Glacier National Park fell under the authority of the National Park Service. Charged with managing all of the country’s national parks, the agency sought to further conserve Glacier National Park’s wonderful landscape and enhance its accessibility. To that end, the National Park Service started developing a 53-mile-long road that navigated deep into the park. Completed during the Great Depression, the Going-to-the-Sun Road dramatically increased the ability of tourists to experience the majesty of Glacier National Park. The National Park Service oversaw additional construction projects that further improved guest access throughout the 1930s and 1940s, with much of the work done through the Civilian Conservation Corps. Today, the National Park Service continues to promote and protect the serene environment of Glacier National Park. Indeed, millions of people arrive every year to explore the park’s current 1,500 square miles of verdant forest, turquoise lakes, and towering mountain tops. Contemporary travelers also remain mesmerized by the countless species of plants and animals that live within its borders, including wolverines, bald eagles, and Canadian lynxes. Perhaps the greatest attraction on-site are the 25 prehistoric glaciers that remain active in the park. Due to its wonderfully conserved geography and ecosystem, Glacier National Park even bears a venerable distinction as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. (It specifically shares this title alongside the neighboring Waterton Lakes National Park, which is located right across the border in Canada.)

-

About the Architecture +

Swiss chalets themselves were once rustic cottages that first emerged as seasonal farmhouses around the height of the Middle Ages. Indeed, the Swiss chalet was a refuge for cattle herders, who would bring their livestock up the mountain ranges during the warmer months. The house functioned as a secondary home, within which the farmers would create a variety of dairy products for trade. But the chalets lost their original purpose as time passed, gradually turning into quaint holiday homes instead. The main reason behind the transformation was the emergence of the Swiss Alps as a popular tourist destination in the 19th century, specifically among the British and the French. They eventually discovered the many chalets scattered around the country and began buying them up in great numbers. The foreigners subsequently renovated the chalets to reflect their romanticized views of alpine life in Switzerland. Soon enough, the new iteration of the chalet had swept across the region. Many natives went as far as to alter their own homes to resemble the aesthetic, essentially making the architecture “Swiss” in the process. Many largescale commercial buildings in Switzerland eventually featured the style, too, including restaurants, storefronts, and hotels. Architects from across Europe soon replicated the architectural form in their own work, with even a few Americans—like Kirtland Kelsey Cutter—using the design regularly. The chalets and their spinoffs were typically very beautiful, despite the rusticity of their layout. Set upon a rectangular foundation, the buildings were most easily recognized for their widely gabled roofs and facades of carved details and wooden balconies. Other iconic features included exposed construction beams, large windows, and weatherboarding.

-

Famous Historic Guests +

Groucho Marx, comedian and actor who made 13 feature length films as part of the famous comedy act, the Marx Brothers.

John D. Rockefeller, founder of the Standard Oil Company and one of America’s most influential businesspeople.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 32nd President of the United States (1933 – 1945)