Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

Discover the Phantom Ranch with its innovative architecture brought about by the necessity of having mules transport building supplies to the lodge site.

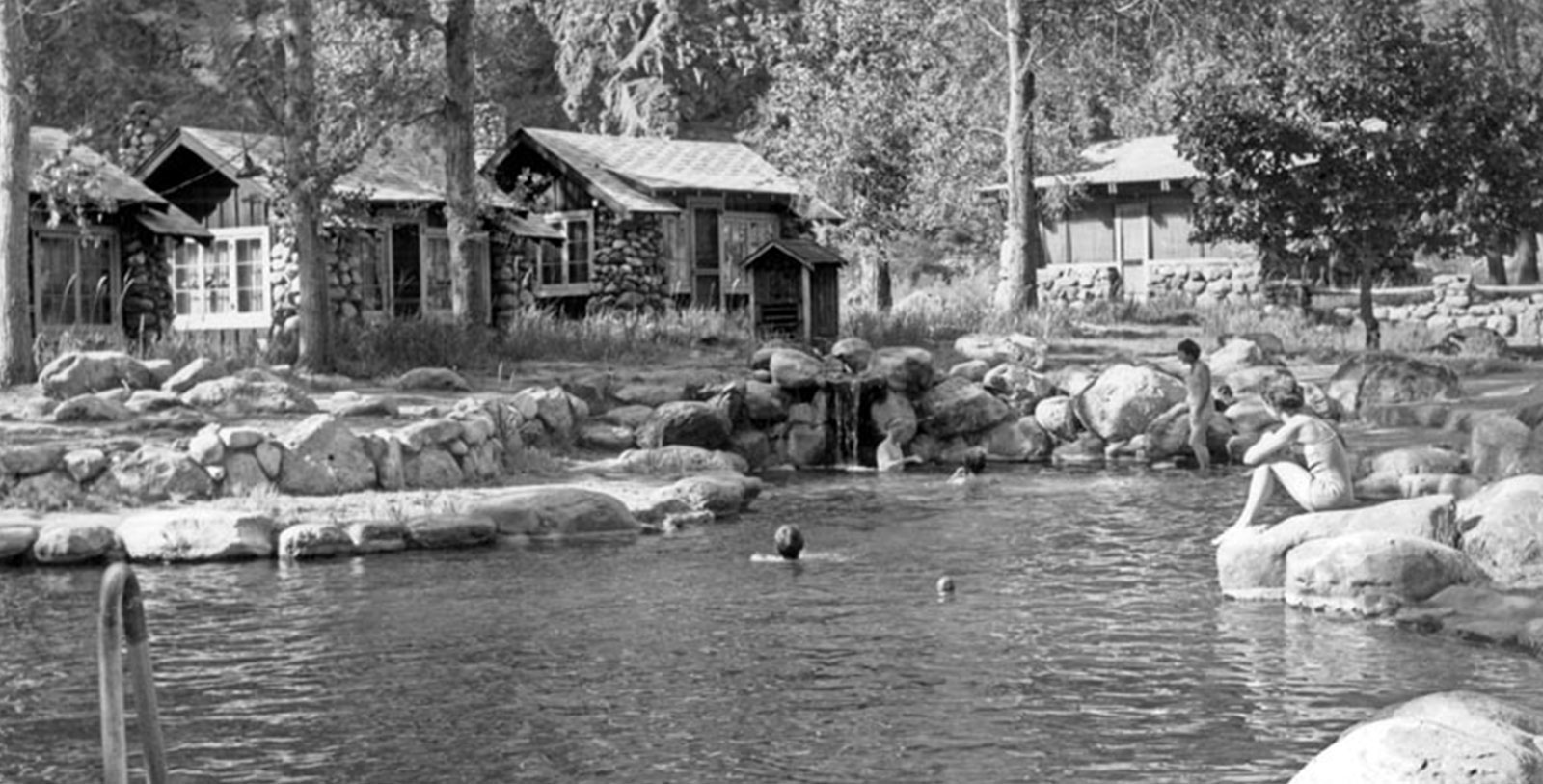

The history of Phantom Ranch can actually be traced back to the early 20th century, when a number of entrepreneurs started developing the northern section of the Grand Canyon to host visitors who yearned to experience its majesty. In 1903, Edwin D. Woolley Jr. specifically formed the Grand Canyon Transportation Company with the intent on creating a tourist compound in the North Rim that could rival similar facilities that the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway was constructing nearby. Woolley decided to create his prospective site close to Bright Angel Creek, after reviewing the research featured in a federal geological report authored by François E. Matthes a year prior. Work then began on transforming an ancient Native American pathway that followed Bright Angel Creek down to the Colorado River. Known as “Bright Angel Trail,” the work on the road was exhausting—many pickaxes and chisels were used to ultimately carve a jagged two-mile route trough the rugged terrain. To help expedite the project’s completion, Woolley eventually hired his son-in-law, David Rust, to act as the main supervising manager. Thanks to Rust’s oversight, the team quickly finished constructing the trail in 1907. Among the last acts they pursued involved the creation of Woolley’s tourist destination—a campsite at a shallow ford aside Bright Angel Creek called “Rust Camp.” Despite its quaint character, Rust and his team had set up several unique visitor tents, as well as a few agricultural structures that could provide a source of sustenance. They even laid an irrigation system and planted dozens of beautiful cottonwood trees around the perimeter.

Much as Woolley had hoped, the Rust Camp became one of the Grand Canyon’s most popular places for visitors to stay while exploring the area. In fact, U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt used the facility as his headquarters on a multi-week hunting trip for mountain lions across the North Rim. In honor of Roosevelt’s time at the campsite, Woolley renamed the destination “Roosevelt Camp.” But Woolley would not operate the site for much longer, as his permit to run the business was revoked during World War I. Nevertheless, Roosevelt Camp was eventually renovated by the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway once the greater Grand Canyon became a national park in 1919. The railway subsequently partnered with the Fred Harvey Company to manage the camp, which requested that the latter find more permanent lodging for the location. To that end, the Fred Harvey Company commissioned its lead architect, Mary E.J. Colter, to spearhead the design of a series of beautiful guest cabins. Colter went to work vigorously in 1921, designing four cabins that accommodated four beds each, as well as a lodge and more formal dining hall. All showcased her unique interpretation of National Park Service Rustic architecture, which relied upon a personalized a synthesis of American Southwest aesthetics and the Arts and Crats movement. Interestingly, Colter built the new structures with building materials located in the immediate vicinity. Recognizing the steep incline of the surrounding canyon walls, Colter wound up insisting that the project utilize local stone and wood to ensure that it remained on schedule.

Thanks to Colter’s ingenuity, the work took a few months and $20,000 to finish. When the entire facility was ready to debut in 1922, Colter suggested that its new name be “Phantom Ranch” in a likely homage to the neighboring Phantom Canyon. Nevertheless, Phantom Ranch quickly built upon the reputation of its predecessors and further solidified its status as a premier vacation hotspot in northern Arizona. Indeed, the site was soon hosting all kinds of influential individuals, including politicians, entertainers, and even European royalty. (One of the first guests were future Swedish monarchs, Prince Gustaf Adolf and Lady Louise Mountbatten, who visited in 1926.) To accommodate the rising numbers of enthusiastic guests arriving at Phantom Ranch, Colter herself oversaw the expansion of the facility throughout the 1920s. She eventually constructed a recreation hall, a wooden bath house, and eight new cabins, among other buildings. This work continued well into the 1930s, too, when members of the Civilian Conservation Corps installed improved sewage lines, a swimming pool, and a telephone system. Interest with Phantom Ranch only continued to grow throughout the rest of the 20th century, as did the impressive guest list of individuals who decided to stay. For instance, Senator Robert Kennedy and his family spent four days at Phantom Ranch amid a greater trip to see the Grand Canyon in 1967. Today, Phantom Ranch proudly remains one of the finest places to experience the magnificence of Grand Canyon National Park. A member of Historic Hotels of America since 2012, cultural heritage travelers in particular are certain to appreciate its rich heritage and spectacular views.

-

About the Location +

Considered one of the legendary “Wonders of the World,” the Grand Canyon is among the most iconic places to experience in the whole United States. The Grand Canyon is a gorgeous gorge cut into the Colorado River, made from five to six-million years’ worth of constant erosion. It is also massive—the entire natural landmark measures 277 miles in length, up to 18 miles in width, and a mile deep. In fact, the entire Grand Canyon covers more than 1.2 million acres of the Colorado Plateau in northwestern Arizona. Some of the most historic geological formations in the country are located within the Grand Canyon, too, with the most notable being the Vishnu Basement Rock. Dating back nearly two millennia, much of the stone has granted geologists the unprecedented ability to study the evolution of the North American continent. Despite the semi-arid climate that defines the geography, the Grand Canyon is nonetheless full of life. The site is the home of several major ecosystems, specifically the following five biomes: Canadian, Hudsonian, Transition, Lower Sonoran, and Upper Sonoran. As such, the Grand Canyon is subsequently home to over 500 unique species of animal, as well as more than 1,500 different types of plants. Many of those lifeforms are found in few other places around the world, including the bighorn sheep, mule deer, and bison. The profound amount of flora and fauna has even made the Grand Canyon a vast repository for distinctive fossils. Scientists have discovered countless fossils within the walls, like crinoids, brachiopods, and ancient insects. The local fossil record has also indicated that the Grand Canyon hosted life—albeit in a very different environment—as far back as the Precambrian Era!

The history of human interaction with the Grand Canyon is more recent comparatively, as the earliest Native Americans originally inhabited the location just a few hundred years ago. The first were the Ancestral Pueblo, who were then followed by the likes of the Paiute, Navajo, Hopi, and Cohonina. (In fact, some of those people continue to reside throughout the Grand Canyon today, such as the descendants of the Cohonina—the Yuman, Hualapai, and the Havasupai.) However, the local Native Americans were later visited by individuals of European ancestry centuries later, starting with the arrival of several Spanish conquistadors during the 1500s. American prospectors eventually began investigating the site for ore deposits of gold and copper following the Mexican-American War. Over time, word spread of the destination’s inherent beauty, which prompted the U.S. government to sponsor its own expeditions to the Grand Canyon. Perhaps the most famous journey undertaken was that of geologist John Wesley Powell, who created a comprehensive series of maps throughout the 1870s. (Powell was also the person responsible for giving the area the name “Grand Canyon.”) Amid the ongoing geological surveys of the Grand Canyon, a number of American pioneers began settling along a portion of its southern rim. While the pioneers were originally interested in mining, they gradually started building a vibrant local tourism industry centered on the Grand Canyon itself. They specifically offered guided tours into the lower segments of the Grand Canyon, and built their own hotels to cater to the new guests whom they entertained.

By the 1880s, the Grand Canyon had emerged as one of the country’s most popular tourist sites. The great interest in the Grand Canyon inspired Congress to try and preserve it as a national park, with Senator Benjamin Harrison sponsoring several bills throughout the Gilded Age. When those efforts were unsuccessful, Harrison decided to protect the Grand Canyon as reserve while serving as U.S. President in 1893. Another U.S. President—Theodore Roosevelt—further helped conserve the the Grand Canyon by declaring it a National Monument in 1908. But legislation to turn the Grand Canyon into a national park continued to languish in the U.S. Senate for many years thereafter. Thankfully, Congress finally managed to secure enough support to pass the Grand Canyon National Park Act, which President Woodrow Wilson signed into law in 1919. Grand Canyon National Park has since become one of the most popular sites within the National Park Service system. Indeed, the location hosted more than 4.5 million people alone in 2021. It is also considered one of the most culturally significant, receiving a coveted designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site during the 1970s. Many of the park’s cultural attractions are split between two distinctive regions, the South Rim and the North Rim. An amazing assortment of hiking trails proliferate throughout each section, as do a number of spectacular spots to go sightseeing, biking, and rafting. Furthermore, the South Rim is home to several famous historic buildings, including the Hopi House, Lookout Studio, and the Desert View Watchtower. All are located within the Grand Canyon Village, a planned visitor community run by the National Park Service that bears a designation as a U.S. National Historic Landmark.

-

About the Architecture +

Phantom Ranch stands today as brilliant examples of National Park Service Rustic architecture. As the name would suggest, the form first became prominent in the United States before it spread throughout the rest of North America. Architect Herbert Maier was central toward conceptualizing the aesthetic while he was studying the Arts and Crafts movement at the University of California, Berkeley, in the early 20th century. Rejecting the design aesthetics of industrialized society, Maier created an architectural form that utilized building materials to better connect a structure to its natural surroundings. Following his graduation from school, he quickly set about designing several structures with his novel architectural approach. Maier found a particularly receptive audience at the National Park Service, as many alumni—including his friend Ansel F. Hall—had graduated from the University of California, Berkeley around the same time. Other architects—such as Mary E.J. Colter—simultaneously mimicked Maier’s mentality and contributed their own variations to the style. Indeed, the synthesis of many unique interpretations helped create a cohesive form that soon became widespread throughout the country. Many state governments particularly embraced the eclectic design philosophy, using the aesthetic to create all kinds of public structures within their own park systems. Even the National Park Service began utilizing the form for its official construction projects, eventually making the architectural style synonymous with the organization itself! National Park Service Rustic only became more widespread in America when the Civilian Conservation Corps began erecting dozens of new park structures during the 1930s. But its popularity throughout North America had waned by the middle of the century, as architects looked to newer design philosophies. Nevertheless, National Park Service Rustic endured to become one of America’s most distinctive and historic architectural styles.

-

Famous Historic Guests +

Tyrone Power, actor known for roles in films like Solomon and Sheba, Jesse James, and Witness for the Protection.

Signe Hasso, actress known for her roles in films like Heaven Can Wait, A Scandal in Paris, and A Double Life.

Barry Goldwater, U.S. Senator from Arizona (1969 – 1987)

Robert F. Kennedy, U.S. Attorney General and Senator from New York (1965 – 1968)

Lady Louise Mountbatten, Queen consort of Sweden (1950 – 1965)

King Gustav VI Adolf (1950 – 1973)

King Albert II of Belgium (1993 – 2013)

-

Women in History +

Mary E.J. Colter: The architect responsible for giving Phantom Ranch its iconic appearance, Mary E.J. Colter is remembered today as one of the most prolific architects in American history. Not only is Colter responsible for helping establish National Park Service Rustic architecture as a style, but she also managed to promote her work at a time when architectural design was a male-dominated industry. Born in Pittsburgh right after the American Civil War, Colter moved around the country with her family before finally settling down in St. Paul, Minnesota. From there, Cotler began studying architecture and eventually enrolled into the California School of Design at the height of the Gilded Age. After relocating back to St. Paul to teach architecture for a few years, Colter secured a position as an interior decorator with the esteemed hotel business, the Fred Harvey Company, in 1902. While only seasonal in nature, she nonetheless made a memorable first impression. For instance, her work with the Alvarado Hotel’s special Indian Building in Albuquerque, New Mexico, was regarded as an absolute masterpiece. (The Alvarado Hotel is no longer standing, as the building’s owner, the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway, demolished it during the 1970s.)

By 1910, Colter had become a permanent, full-time employee of the Fred Harvey Company, designing numerous interior designs. In fact, Colter had established herself as the led architect for many of the corporation’s numerous buildings projects throughout the Southwestern United States. She specifically affected the designs of many outstanding hotels, including La Fonda, which the Fred Harvey Company had managed for a time in the early 20th century. Perhaps Colter’s finest work transpired in Grand Canyon National Park during the 1930s, where she created and renovated several beautiful recreational structures, like the hotels Phantom Ranch and the Bright Angel Lodge & Cabins. Colter specifically synthesized numerous historic architectural examples throughout the project, such as Spanish Colonial, Mission Revival, and the Arts and Crafts Movement. Her architectural approach subsequently inspired many other contemporary architects, including those employed on behalf of the National Park Service. Indeed, the National Park Service would even incorporate aspects of Colter’s designs into its greater “National Park Service Rustic” aesthetic. Today, Mary E.J. Colter is hailed as one of the most influential architects of 20th-century America, as well as a pioneer for women who have since followed her into the field of professional architecture.

Guest Historian Series

Read Guest Historian SeriesNobody Asked Me, But… No.206;

Hotel History: Mary Elizabeth Jane Coulter (1869 – 1958)

By Stanley Turkel, CMHS

A pioneering American woman architect and interior designer whose distinct architectural knowledge was steeped in the culture and landscape of the Southwest. As the architectural historian for the Fred Harvey Company, she designed hotels, restaurants, gift shops and rest areas along the major routes of the Atchison, Topeka and Sante Fe Railway from 1902 until her retirement in 1948. Yet few of the nearly five million people who visit the Grand Canyon National Park every year are aware of Mary Colter and her accomplishments. No wonder she’s been called “the best-known unknown architect in the national parks.”

Born on April 4, 1869 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, she was the daughter of Irish immigrants William Colter, a merchant, and Rebecca Crozier, a milliner. She experienced a transient childhood moving with her family from Pennsylvania to Texas and Colorado before finally settling down in Saint Paul, Minnesota at the age of eleven. In 1880, Saint Paul had a population of 40,000 people and a large minority of Sioux Indians, survivors of the Dakota War of 1862 which forced many to leave the newly-formed state.

Mary Colter graduated from high school at the age of 14 and after her father died she attended the California School of Design (now the San Francisco Art Institute) until 1891 where she studied art and design. Established by the San Francisco Art Association in 1874, the California School of Design, one of the first art schools in the West, provided its students with a comprehensive art education. For fifteen years Colter taught drawing at Mechanic Arts High School and lectured at the University of Minnesota Extension School. Her first design commission came when she met Minnie Harvey Huckel, daughter of the founder of the Fred Harvey Company.

In 1902, Colter started working for the Fred Harvey Company as an interior designer and practical architect. Her first assignment was to create an interior design for the Harvey Company’s newest project: the Indian Building adjacent to Harvey’s Hotel Alvarado in Albuquerque, New Mexico. The Alvarado was designed by architect Charles Frederick Whittlesey (1867-1941) who trained in the Chicago office of Louis Sullivan. In 1900, at the age of thirty-three, Whittlesey was appointed Chief Architect for the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway. He designed the El Tovar Hotel at the south rim of the Grand Canyon in Arizona and the Alvarado Hotel in Albuquerque with eighty-eight guestrooms, parlors, a barbershop, reading room and restaurant.

Mary Colter’s design for the adjacent Indian Building helped to launch the Harvey Company’s long-time sponsorship of Indian arts and crafts. The Albuquerque Journal Democrat reported on May 11, 1902 that the Alvarado Hotel “opened in a burst of rhetoric, a flow of red carpet and the glow of myriad brilliant electric lights with hopes that it would attract the wealthier classes to stop in Albuquerque on their travels to the West.”

Fred Harvey brought civilization, community and industry to the Wild West. His business eventually included restaurants, hotels, newsstands and dining cars on the Sante Fe Railroad. The partnership with the Atchison, Topeka and Sante Fe introduced many new tourists to the American Southwest by making rail travel comfortable and adventurous. Employing many Native-American artists, the Fred Harvey Company also collected indigenous examples of basketry, beadwork, Kachina dolls and a lively collection of exotic artifacts, handicrafts and Mission-style furniture.

Mary Colter’s Indian Building contained work and exhibit rooms with Indian basketmakers, silversmiths, potters and weavers at work. It launched the Harvey Company’s long-standing sponsorship of Indian arts and crafts. Mary Colter designed a new cocktail lounge in 1940 in the Alvarado and named it La Cocina Cantina to capture the design of an early Spanish kitchen.

From 1902 through 1948, Mary Colter served as the primary designer for the Fred Harvey Company, completing designs for twenty-one hotels, restaurants, lounges, curio shops, lobbies and rest areas along the major routes of the Atchison, Topeka and Sante Fe Railway. She captured the romance and mystery of the American Southwest and Native American artistic culture. Some characteristic features of her designs were tiny windows allowing shafts of light to accent red sandstone walls; a low ceiling of saplings and twigs resting on peeled log beams; a hacienda enclosing an intimate courtyard; a rough boulder structure, built into the earth as if part of a natural rock formation. These details shaped American visions of the Southwest for generations to come.

All twenty-one of Colter’s projects reveal her acute understanding of and commitment to both the natural and cultural landscape in which she worked. Through her interior designs, Colter demonstrated a spirited irreverence in her compositions, offering a clever demonstration of her own inventive Arts and Crafts sensibility.

Meanwhile, in the projects she termed “re-creations,” such as the Hopi House (1905) and Desert View Watchtower (1933) in Grand Canyon National Park, she almost always followed the architectural features of the original prototypes.

Employing indigenous Native American builders, demanding the use of local materials when possible, and attending to minute historical details obtained through research expeditions to various Indian historical ruins, Colter strove for stylistic verisimilitude without attempting to make, as she put it, a “copy,” or a “replica.”

In her smaller-scaled tourist architecture at the Grand Canyon, Colter introduced more innovative designs, including those for Hermit’s Rest and Lookout Studio (both 1914), places for Canyon visitors to stop that were intended to be “hidden under the rim,” according to Colter.

In Lookout Studio, she created a single-level, horizontal structure of rusticated Kaibab limestone that mimicked the stratification of the eroded rock below, ensuring unobstructed views from other promontories by means of architectural camouflage which allowed the innate drama of the Grand Canyon to enrich tourists’ experiences.

Other Harvey projects drew Colter away from the Grand Canyon, giving her the opportunity to design station-hotels along the Sante Fe Railway line, through which her architectural vision could manifest at a great scale. Of the El Navajo Hotel in Gallup, New Mexico (1923), she wrote, “I have always longed to carry out the true Indian idea, to plan a hotel strictly Indian with none of the conventional modern motifs,” probably referring to the ersatz Native Americana common to so many of the inferior hotels arising in the Southwest after World War I. Both the El Navajo in Gallup, New Mexico and La Posada in Winslow, Arizona, demonstrated Colter’s engagement with regional design issues and evoked the originality and wit of her earlier projects.

Colter retired to Santa Fe in 1948 and died there in 1958. Frank Waters, the great historian and expert on Native Americans of the Southwest, in his book Masked Gods: Navaho and Pueblo Ceremonialism (1950), recalled Mary Jane Colter:

“For years, an incomprehensible woman in pants, she rode horseback through the Four Corners making sketches of prehistoric ruins, studying details of construction, the composition of globes and washes. She could teach masons how to lay adobe bricks and plasters how to mix washes.”

Although her contemporaries often called her a “decorator,” her projects, of which four– Hopi House, Hermit’s Rest, Lookout Studio, and Desert View Watchtower – have been designated National Historic Landmarks, suggest that “architect” would be a more accurate and enduring description.

In early 2018, a book entitled False Architect: The Mary Colter Hoax by Fred Shaw stated that Colter was never trained or certified as an architect. It claimed that she falsely took credit for designs produced by others.

In response to this provocative thesis, Allan Affeldt, co-owner and operator of the La Posado Hotel, Winslow, Arizona wrote in September 2018: “All of us in the Harvey world are quite upset about the book. Shaw is clearly a misogynist.” Affeldt added:

“The attributions of Colter’s works to Curtis and others is preposterous, and obviously discounted by the many including Harvey family with direct knowledge of Colter and the buildings. We have collectively decided it best to ignore these self-published rantings and not give Shaw a podium for his hatred.”

*****

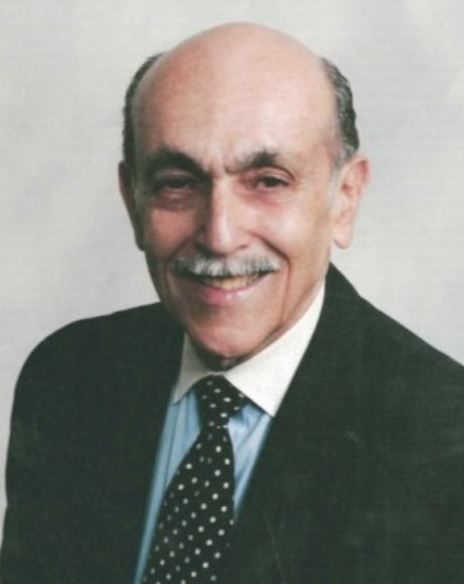

About Stanley Turkel, CMHS

Stanley Turkel was designated as the 2014 and 2015 Historian of the Year by Historic Hotels of America, the official program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. This award is presented to an individual for making a unique contribution in the research and presentation of history and whose work has encouraged a wide discussion, greater understanding and enthusiasm for American History. Turkel is also the most widely-published hotel consultant in the United States. He operates his hotel consulting practice serving as an expert witness in hotel-related cases, provides asset management and hotel franchising consultation. He is certified as a Master Hotel Supplier Emeritus by the Educational Institute of the American Hotel and Lodging Association.

Stanley Turkel’s new book, Great American Hotel Architects is available. It is his eighth hotel history book, which features twelve architects who designed 94 hotels from 1878 to 1948: Warren & Wetmore, Henry J. Hardenbergh, Schultze & Weaver, Mary Elizabeth Jane Colter, Bruce Price, Mulliken & Moeller, McKim, Mead & White, Carrere & Hastings, Julia Morgan, Emery Roth, Trowbridge & Livingston, George B. Post and Sons.

Interested persons can order copies from the publisher AuthorHouse by posting “Great American Hotel Architects” by Stanley Turkel.

Other Published Hotel Books include:

- Great American Hoteliers: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2009)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels in New York (2011)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels East of the Mississippi (2013)

- Hotel Mavens: Lucius M. Boomer, George C. Boldt, Oscar of the Waldorf (2014)

- Great American Hoteliers Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2016)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels West of the Mississippi (2017)

- Hotel Mavens Volume 2: Henry Morrison Flagler, Henry Bradley Plant, Carl Graham Fisher (2018)

All of these books can be ordered from AuthorHouse by visiting www.stanleyturkel.com and clicking on the book’s title.