Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

Discover the St. Louis Union Station Hotel Curio Collection by Hilton. After the heyday of railroad travel, the hotel originated in 1977 but underwent a modern refresh in 2007. It preserves its historic elements in a setting for 21st century travelers.

St. Louis Union Station Hotel, Curio Collection by Hilton, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 1991, dates back to 1894.

VIEW TIMELINE

Union Station | Living St. Louis

Living St. Louis producer Anne-Marie Berger looks at the history of Union Station. At its peak during World War II, Union Station was a central transportation hub for the country. Over 2 million soldiers traveled through the station monthly. Today, it is a tourist attraction and an area of commerce.

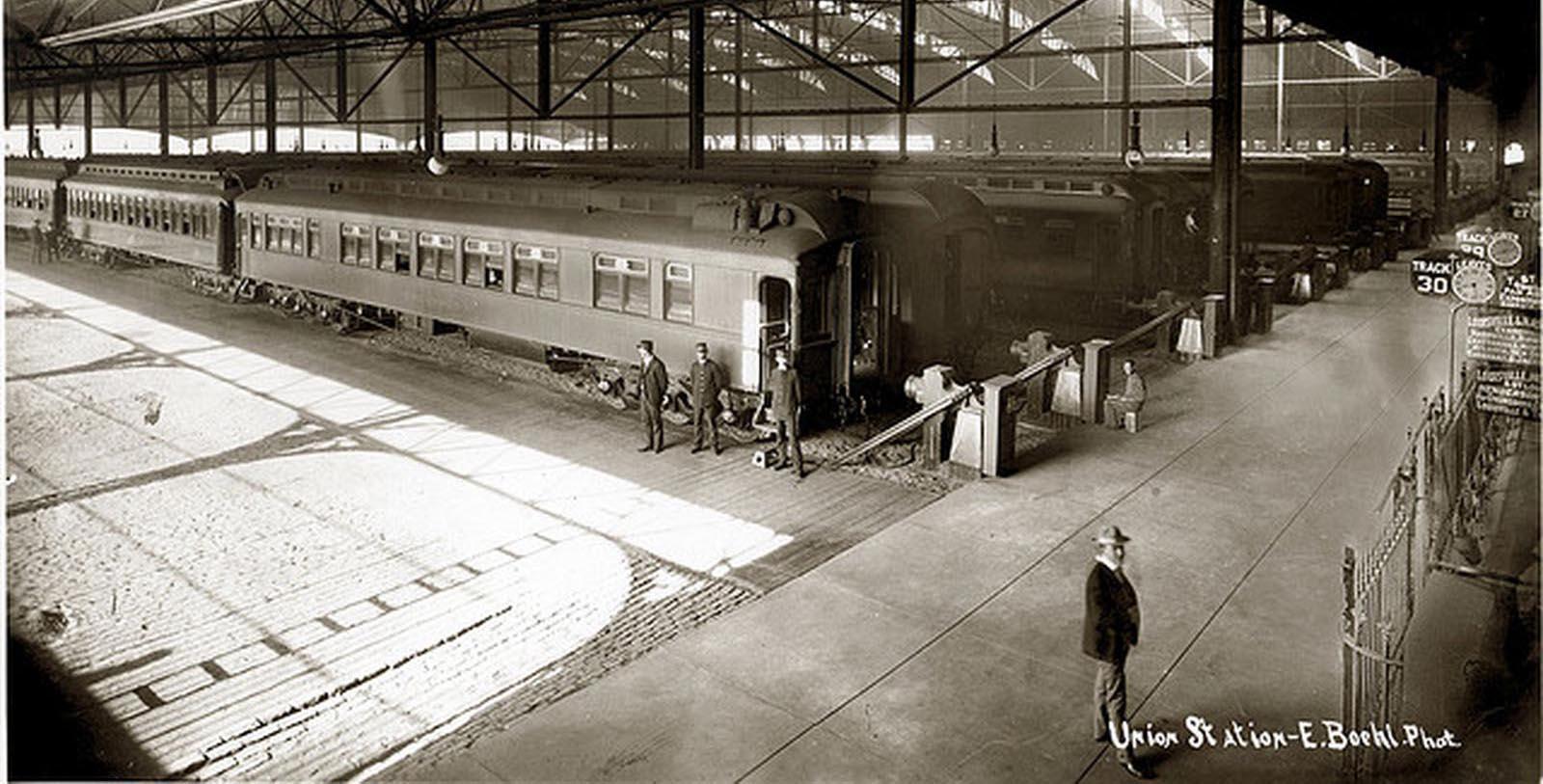

WATCH NOWA U.S. National Historic Landmark, the St. Louis Union Station Hotel, Curio Collection by Hilton, has a deeply fascinating heritage. Its origins date back to the height of the Gilded Age, when it was developed to operate as a major train depot. On September 1, 1894, the iconic Union Station opened its doors for the first time after months of arduous construction. Local architect Theodore Link had created its design amid a contest held at the behest of the Terminal Railroad Association of St. Louis. Given control over the entire project, Link subsequently created a magnificent, sprawling complex that stood as a masterpiece of American architecture. The focal point of his design were its civilian facilities, like the gorgeous Grand Hall and a stunning boutique hostelry known as the “Terminal Hotel.” The Grand Hall itself was specifically constructed to inspire the countless guests that were expected to arrive daily. He had mainly modeled the space to resemble a passageway inside a medieval castle, with the walled French city of Carcassonne as his source of inspiration. Ornate details proliferated throughout the space, too, such as spectacular gold leafing, wide stained-glass windows, and wall carvings made from Indiana limestone. A stunning, 65-foot barrel-vaulted ceiling crested the Grand Hall, anchored by a beautiful, wrought-iron chandelier. (Weighing an impressive two tons, the fixture required some 350 light bulbs to function properly!) Meanwhile, Link had worked closely with engineer George H. Pegram to create what became the world’s largest train shed ever constructed during the 19th century. Located next to the station’s extravagant headhouse, it hosted 32 different tracks under an expansive, steel roof!

In the years that followed, the new St. Louis Union Station quickly became one of the busiest train depots in America. Thousands of people subsequently passed through its Grand Hall, driving demand for its services to new heights. In fact, nearly two million travelers were arriving each day in the middle of World War II. Some of the country’s most influential figures were eventually seen inside the complex as well, like Joan Crawford, Kirk Douglas, and Joe DiMaggio. President Harry S. Truman was also famously photographed at St. Louis Union Station right after he historically beat New York Governor Thomas A. Dewey in the 1948 presidential election. The popularity with the station’s services even prompted the Terminal Railroad Association of St. Louis to expand the building constantly throughout the early 1900s. Nevertheless, St. Louis Union Station’s popularity was not destined to last forever, especially once automobiles emerged as the primary mode of travel for most Americans. Use of the depot’s services declined throughout the 1960s, with the facility becoming virtually obsolete by 1978. Salvation fortunately arrived in 1985, after global design firm HOK invested $150 million into renovating the site. The work was incredibly comprehensive, transforming the former train station into a lavish hotel that boasted 539 guestrooms rooms, a shopping center, and numerous dining outlets. Now known as the “St. Louis Union Station Hotel, Curio Collection by Hilton,” the hotel continues to serve the countless travelers who come to St. Louis every year. Indeed, the spirit of the original Union Station is still very much alive and well.

-

About the Location +

Millennia ago, the site of present-day St. Louis was once inhabited by Native Americans of the ancient Mississippian culture. Due to the area’s proximity to both the Mississippi and Missouri rivers, thousands of indigenous people frequented the location for generations. The locale held spiritual significance among the Mississippians, who constructed dozens of earthen mounds as religious monuments. Known as the Cahokia Mounds, the earthworks were one of the most enduring geological features in the region. Indeed, the formations even gave St. Louis the moniker of “Mound City” during its formative years. (Unfortunately, most were destroyed throughout the 19th century as St. Louis expanded in size. Only a small segment survives as the Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site.) Nevertheless, St. Louis itself first came into existence when two French fur trappers—Pierre Laclede Liguest and his stepson, Auguste Chouteau—opened a trading post in 1764. While the area was no longer under French control, Liguest proceeded to develop his small community via a land grant given to him earlier by King Louis XV of France. He subsequently began creating the village a year later, naming it after another French monarch, King Louis IX. Over time, settlers from Canada and France began to arrive in St. Louis, who were attracted by its vibrant local fur trading industry.

St. Louis and the surrounding countryside only to returned to France during the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte. (It had originally lost it to Spain in the wake of the Seven Years’ War.) But St. Louis then became a part of the nascent United States after Bonaparte sold the surrounding area to the Jefferson administration via the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. It immediately assumed great strategic importance to President Thomas Jefferson, who used it as the final launching point for the historic Lewis and Clark Expedition. St. Louis remained a gateway into the American West for many years thereafter, attracting scores of migrants from across the country over the following decades. Their numbers were supplemented by thousands of European immigrants, specifically Irish and German settlers who wished to create their own communities out on the frontier. Even though a majority of the settlers merely used St. Louis as a springboard to go further west, quite a few stayed in town and made it their home. As such, St. Louis underwent unprecedented growth as its population swelled in size. In fact, the settlement had rapidly transformed into a city mere decades after the American Revolution. St. Louis continued to expand throughout the rest of the 19th century, with its residents voting to establish a home-rule charter during the Gilded Age.

The city continued to be a nexus for travel toward the Pacific coast in the early 20th century, although its status as middle America’s preeminent transportation hub had been supplanted by Chicago. St. Louis continued to prosper, however, thanks to the emergence of largescale industrialization. Perhaps the greatest symbol of St. Louis’s economic success was the renowned Eads Bridge, which helped ship countless manufactured goods all over the nation. Its rising prestige even got it to host two major international events in 1904--the Louisiana Purchase Exposition and the Summer Olympics! But the city’s prosperity came to an end unfortunately, as it entered a period of decline after World War II. Undeterred, a coalition of local civic leaders and businesspeople sought to reverse St. Louis’ stagnation. Beginning in the 1960s, those concerned citizens launched dozens of construction projects that revitalized downtown St. Louis. Some of the greatest plans led to the creation of well-known landmarks like the ceremonial Gateway Arch and Busch Memorial Stadium, home to the city’s iconic St. Louis Cardinals. The redevelopment efforts worked brilliantly, which resurrected St. Louis’ identity as one of America’s leading cities by the century’s end. St. Louis is still an influential metropolis that now attracts cultural heritage travelers from across the world year after year.

-

About the Architecture +

The St. Louis Union Station Hotel, Curio Collection by Hilton, shows some of the finest elements of Romanesque Revival architecture. Romanesque Revival-style architecture is a wonderful architectural style that first appeared in North America in the middle of the 19th century, as design principles from both Rome and medieval Europe found a popular audience. Architects interested in specializing in Romanesque Revival-themed architecture specifically studied the works of Norman and Lombard engineers who were active in the 11th and 12th centuries. Structures created with the aesthetic are commonly defined by their pronounced round arches and round towers. Yet, those grand archways and towers were far less ostentatious than their historic counterparts located on the other side of the Atlantic. Romanesque Revival-style architecture also implemented squat columns, decorative wall carvings, and the extensive use of masonry. But architects would sometimes favor wood over bricks or stones due to financial concerns. Indeed, some of the hotel’s most stunning architectural components reflected such design elements, specifically the gorgeous columns and grand arches that proliferated throughout its iconic Grand Hall.

The first wave of Romanesque Revival-style architecture impacted North America in the 1840s and 1850s, appearing in cities like Washington, D.C., and Toronto. University College at the greater University of Toronto is one such example of a brilliant Romanesque Revival-inspired structure to emerge at the time. But the general public in both the United States and Canada did not fully embrace the aesthetic, preferring the tastes of Italianate and Gothic Revival architecture at the time. It was not until an American architect named Henry Hobson Richardson started using the form in the late 1800s that Romanesque Revival style finally became popular. A graduate from the renowned École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, Richardson developed numerous designs in places like New York City, Boston, and Detroit. His approach to Romanesque Revival style was somewhat different, as it also incorporated elements of medieval Mediterranean design principles. His vision of Romanesque Revival-style architecture was soon embraced by other architects, including those in neighboring Canada. Historians today largely refer to Richardson’s design philosophy as “Richardson Romanesque” architecture.

-

Famous Historic Events +

United States Presidential Election of 1948: In the summer of 1948, both the Democratic and Republican parties prepared for a difficult presidential election. Arriving in Philadelphia that June, the Republicans were the first to organize their party’s platform. They subsequently met inside the Philadelphia Convention Center, where they nominated the popular New York Governor Thomas A. Dewey for President of the United States. (The convention goers then elected California Governor Earl Warren to be his running mate. Warren would later serve as the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court amid a period of its history remembered as the “Warren Court.”) Dewey himself pledged to campaign for desegregating the military, equal rights for women, and strong international anticommunist policies, among other issues. Almost immediately, political pundits believed Dewey to be the favorite to win it all. Indeed, grassroots support for the Republican Party had swelled in recent years, with the group taking control of Congress in the previous midterm election cycle. Many strategists interpreted the shift as a sign of growing uneasiness toward the New Deal reform policies that had defined the nation since the early 1930s.

The Democrats subsequently grappled with this belief when they met together inside the Philadelphia Convention Center a couple of weeks later. But unlike their Republican colleagues, the Democrats’ gathered with great tension. For three days, the country’s leading Democratic politicians engaged in rancorous fighting over a range of contentious issues that centered on the incumbency of President Harry S. Truman. (Previously the Vice President of the United States, Truman had originally assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin Delano Roosevelt at the end of World War II.) Critics alleged that the Democratic Party’s diminishing popularity was President Truman’s fault and pleaded with him not to seek reelection. Southern Democrats were particularly hostile to a potential Truman ticket, due to his support for civil rights. Meanwhile, the progressives openly bristled at his known aversion to socialism. In the end, only a slim plurality of the delegates supported Truman, who refused to withdrawal his candidacy. Truman thus won his bid for the Democratic nomination, with Senator Alben Barkley as his Vice President.

Americans spent the following months believing that Truman had no chance of ever defeating Dewey. In fact, numerous media outlets reported polling numbers that were skewed in the governor’s favor. The Chicago Tribune even ran a now-famous issue on Election Day that had the frontpage headline, “Dewey Beats Truman.” But the nation was shocked when it awoke the following morning—Truman had defeated Dewey by a wide margin. The only person who was not stunned was President Truman himself. Despite receiving fractured support from his own party, he nonetheless conducted a vigorous “whistle-stop” campaign over the following months. Arriving from town to town, Truman gave countless speeches before crowds of onlookers. He recognized that his addresses made them energized with their populist, middle-class messaging. The victory was a satisfying achievement for Truman, as he would spend the rest of hist life mocking the journalists who had prematurely announced his defeat. Indeed, one of his first acts involved sarcastically waving a copy of the Chicago Tribune’s Election Day edition before hundreds of supporters at St. Louis Union Station. Truman had specifically hoisted the paper above his head on the open platform of his special train car, which had just finished a two-day trip from Independence, Missouri.

-

Film, TV and Media Connections +

Escape from New York (1981)

-

Women in History +

Today, the St. Louis Union Station Hotel, Curio Collection by Hilton, is a popular family entertainment destination. (In fact, the building is even home to the St. Louis Aquarium, the 200-foot-tall St. Louis Wheel, and a variety of other attractions establishments.) But when this National Historic Landmark building opened in 1894, it was a symbol of the city's position as a hub of commerce and transportation. Legendary restaurateur Fred Harvey opened his Harvey House dining room at Union Station in 1895. (Visitors can dine in the same elegant room now, called the Station Grille.) In its heyday, St. Louis Union Station was the largest and busiest railroad terminal in the nation, with more than two dozen railroads operating from its massive train shed. During the height of World War II in 1943, the Fred Harvey Restaurants at Union Station served more than 2,700,000 meals in their three distinctive dining rooms. Dining with Fred Harvey was an elegant experience with linens imported from Ireland, silver from England, and chinaware from France. Harvey's waitresses were recruited to head west and formed the bulk of the workforce. To be a Harvey Girl, women had to be between the ages of 18-20 and of good character—they even had to sign a contract to stay in their job for one year at a fixed rate of $17.50 per month. The Harvey Girls were housed in dormitories and watched by a “housemother”—they also could not wear make-up, pinch their cheeks, or flirt. Nevertheless, the Harvey Girls helped make the restaurants a fixture in the St. Louis community for years until the station’s eventual conversion at the end of the 20th century.