Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

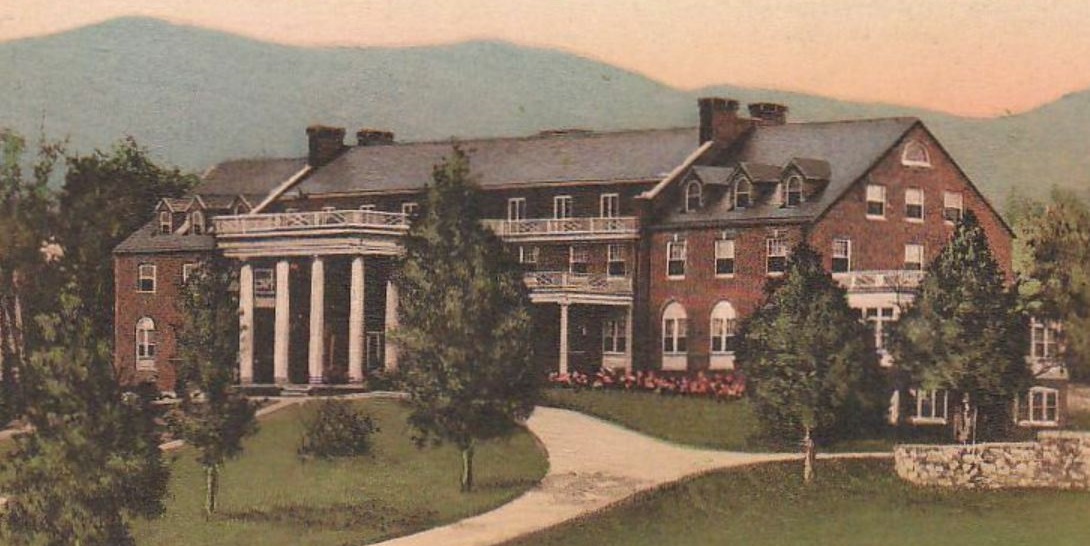

Discover the Mimslyn Inn, a luxurious and comfortable place to feel at home when visiting the stunning Shenandoah Valley.

The Mimslyn Inn, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2008, dates back to 1931.

VIEW TIMELINELocated in the heart of the Shenandoah Valley, The Mimslyn Inn was inducted into Historic Hotels of America in 2008. Its history harkens back to the era of the Great Depression and World War II. In the town of Luray, Henry and Elizabeth Mims owned and operated the existing Hotel Laurance and Mansion Inn. They decided to build another hotel that would rival the elegance of anything else in operation throughout the Shenandoah Valley at the time. Together with Henry’s brothers, the couple began constructing the hotel upon a piece of land that once belonged to a historic estate known as “Aventine Hall.” The family imported all kinds of upscale building materials from across the commonwealth, from high-end stone to durable wood. In fact, the Mims even imported a massive coal-fired steam shovel from Richmond to excavate the ground.

The entire project lasted a total of 15 months, concluding in May of 1931. When contemporaries finally entered into “The Mimslyn Inn,” they noticed a stunning array of brilliant architectural details and lavish amenities. Perhaps its greatest feature was a gorgeous winding staircase that one of Henry’s brothers, JR Mims, Sr., designed himself. To celebrate, the Mims held a massive soiree that was attended by several hundred people. The Mims family graciously welcomed their guests into their new home for many years thereafter, making their inn one of the most beloved in Virginia. This spirit of hospitality has been a distinguishing feature of The Mimslyn Inn ever since.

Today, the historic inn is under ownership of a new family, Mr. and Mrs. Erwin Asam and their sons, Christian and David. They work tirelessly to continue the Mims' legacy of warmth, family, good service, and quality. Most recently, a multimillion-dollar renovation was completed and guests of The Mimslyn Inn can now enjoy the history and heritage of Luray in luxurious accommodations. Thanks to their stewardship, The Mimslyn Inn has continues to be one of the best historic hotels to visit in all of Virginia.

-

About the Location +

Surrounded by verdant farmland and rolling fields, the town of Luray, Virginia, is located in the center of the Shenandoah Valley. This quaint pastoral community has existed for centuries, its founding taking place back at the beginning of the 19th century. Shortly after the start of the War of 1812, William Stage Marye began plotting street grids upon land originally owned by the Ruffner family. Naming the settlement after his ancestral home in Luray, France, he specifically laid out three cross streets along a north-south axis near the Hawksbill Creek. The first lots were initially quite small, only measuring about a half an acre. But over time, the town gradually tripled in size. What spurred this growth was the presence of industry just beyond the town’s borders that had been in operation since the time of the American Revolution. Perhaps the greatest facility in the area was Direk Pennypacker, who operated a massive furnace just north of Luray. Nevertheless, the town’s proximity to the Valley Pike (originally called the “Great Wagon Road”) made it a popular spot for merchants to visit as they transported their goods across the valley. As such, Luray possessed several storefronts, a couple of churches, and a steady, permanent population of 500 people by the eve of the American Civil War. Luray’s prosperity even convinced state legislators to make the town the seat of government for the greater Page County in 1845.

Luray nonetheless remained a small, yet affluent community until the arrival of the railroads during the Gilded Age. In 1881, executives with the Norfolk and Western Railroad decided to extend a portion of its main line toward Luray, which they referred to as the “Shenandoah Valley” branch. Operated by a subsidiary called the “Shenandoah Valley Railroad Company,” the line enabled many businesspeople around Luray to ship their goods to newer markets at an unprecedented rate. Great wealth flowed into the town, sparking a wave of industrial and residential construction that lasted for a couple of decades. (Many of those historical structures still survive today and are preserved as part of the Luray Historic District.) But the arrival of the trains caused another important economic development: tourism. Reports from the era indicated that the railroad brought thousands of new people to Luray, many of whom desired to experience a beautiful subterranean system of caves known as the “Luray Caverns.” Discovered in the late 1870s, they featured a stunning array of 40 chambers that guests could easily walk through. The network proved to be so impressive that the Smithsonian Institute even considered it to be one of the nation’s best natural landmarks. The local tourism industry remained strong for many years thereafter, especially once the National Park Service opened Skyline Drive in Shenandoah Valley National Park during the 1930s. Today, Luray remains one of Virginia’s most exciting places to visit in the whole commonwealth.

The Shenandoah Valley itself is one of Virginia’s most historic regions. Originally inhabited by many demographics of Native Americans, the area was gradually settled with a combination of German religious refugees and Scotch-Irish farmers throughout the 18th century. Most migrants who arrived had traveled along the famous Great Wagon Road, which later became known as the “Valley Pike” a century later. Unlike the communities lining the coast, many farms in the valley remained small and slavery far less a fixture. The people also developed a unique regional identify that distanced them somewhat from their fellow Virginians. The region nonetheless earned a significant reputation for its fertile soil, with many referring to it as the commonwealth’s “breadbasket.” This important economic status eventually made it a target for both Union and Confederate armies during the American Civil War. Numerous military campaigns were subsequently waged throughout the Shenandoah Valley, with some of the most famous occurring in 1862 and 1864, respectively. (The sheer volume of fighting has since made the valley one of the most popular regions for Civil War enthusiasts to see in the country.) In the wake of the conflict, the Shenandoah Valley transformed into a premier vacation destination. By the dawn of the 20th century, its historical and natural landmarks were attracting thousands of people from across the nation. The Shenandoah Valley remains a top tourist retreat, particularly among America’s cultural heritage travelers.

-

About the Architecture +

The Mimslyn Inn itself stands as a brilliant example of Georgian Revival-style architecture. Georgian Revival-style architecture itself is a subset of a much more prominent architectural form known as “Colonial Revival.” Colonial Revival architecture today is perhaps the most widely used building form in the entire United States. It reached its zenith at the height of the Gilded Age, where countless Americans turned to the aesthetic to celebrate what they feared was America’s disappearing past. The movement came about in the aftermath of the Centennial International Exhibition of 1876, in which people from across the country traveled to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to commemorate the American Revolution. Many of the exhibitors chose to display cultural representations of 18th-century America, encouraging millions of people across the country to preserve the nation’s history. Architects were among those inspired, who looked to revitalize the design principles of colonial English and Dutch homes. This gradually gave way to a larger embrace of Georgian and Federal-style architecture, which focused exclusively on the country’s formative years. As such, structures built in the style of Colonial Revival architecture—as well as the Georgian Revival-style—featured such components as pilasters, brickwork, and modest, double-hung windows. Symmetrical designs defined their façades, anchored by a central, pedimented front door and simplistic portico. Gable roofs typically topped the buildings, although hipped and gambrel forms were used, too. This building form remained immensely popular for years until largely petering out in late 20th century.