Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

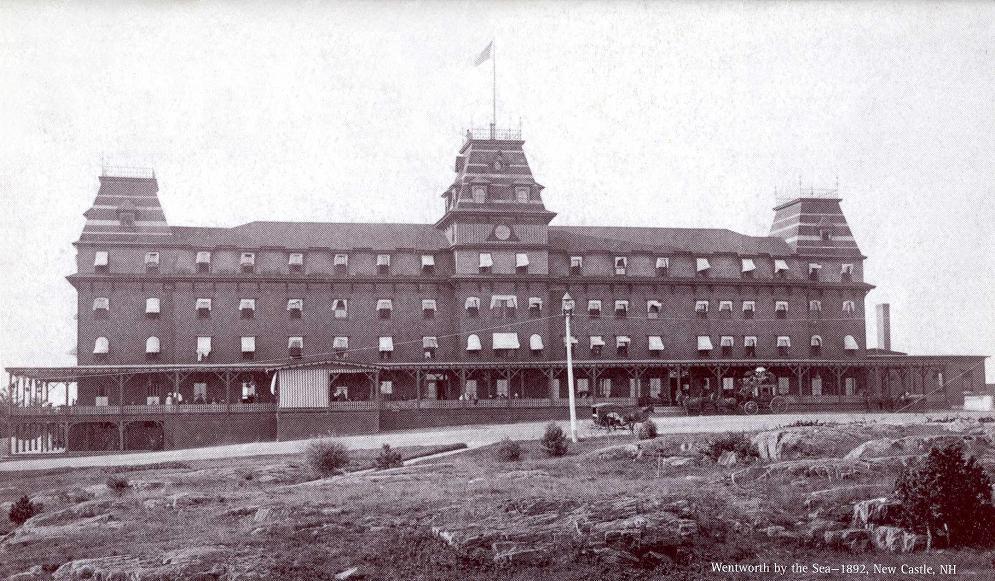

Discover Wentworth by the Sea, the famed "Ship Building," which once hosted the signers of the Portsmouth Peace Treaty in 1905.

Wentworth by the Sea, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2004, dates back to 1874.

VIEW TIMELINE

Wentworth by the Sea Overview

Overlooking the Atlantic Ocean from the island of New Castle, Wentworth by the Sea welcomes guests to one of last grand Portsmouth hotels.

WATCH NOWA member of Historic Hotels of America since 2007, Wentworth by the Sea is among the last great stately resort hotels to grace New Hampshire’s coast. A Boston-based distiller named Daniel Chase first constructed the facility in the 1870s, having relocated from his native Massachusetts a few years prior. Desiring to construct a magnificent seaside holiday destination, he purchased a parcel of land in New Castle from Charles E. Campbell. The acreage specifically resided on Great Island, which straddled the border between New Hampshire and Maine within the Piscataqua River. Campbell actually provided Chase his assistance, and together, the two men constructed the massive hotel in just a matter of months. Debuting as “Wentworth Hall” in 1874, the resort quickly endeared itself among the many travelers who spent their summers vacationing in New England. While the origin of the name “Wentworth” is uncertain, some believed Chase and Campbell decided to honor Samuel Wentworth, who was the very first innkeeper on New Castle’s Great Island. Nevertheless, Chase personally went bankrupt shortly after the hotel’s opening, forcing him to foreclose on the destination. Wentworth Hall subsequently underwent a period of fluid ownership, with a new person seemingly acquiring the building each year. One of its owners—Daniel Chase’s brother—even renamed the location as the “Hotel Wentworth.” Still, the different proprietors cared for the building greatly, investing thousands of dollars into its upkeep. Some also installed new sections onto the building, including a bowling alley, a billiard hall, and a new wing of 20 guestrooms.

Fortunately, this carousel of changing ownership ended in 1879, when beer magnate Frank Jones permanently bought the location. Hotel Wentworth experienced a new series of renovation under Jones, in which both its interior and exterior appearance was significantly modified. For its new façade, Jones chose the popular style of Second Empire architecture that was spreading throughout North American and Europe at the time. Some historians believe that Jones was responsible for specifically installing the resort’s iconic towers, as they closely resembled the ones that sat atop his personal residence in the center of town. And inside, the aspiring hotelier recreated all the interior spaces to resemble the cabins of the great ocean liners of the day. By the time Jones had fully completed the renovations, the Hotel Wentworth could accommodate as many as 450 patrons. The deluge of guests only increased as the 19th century drew to a close, attracting scores of people from across the nation. Some of the resort’s visitors were even among the most powerful individuals in the entire world. For instance, U.S. President Chester A. Arthur was spotted regularly at the Hotel Wentworth whenever he decided to travel north from Washington to visit the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard. Even after Jones died in 1902, the destination managed to retain its prestigious appeal. This rang especially true in 1905, when the Russian and Japanese delegations booked blocks of space at the Hotel Wentworth while they discussed ending the Russo-Japanese War at the behest of then President Theodore Roosevelt.

After undergoing a period of fluid ownership following Jones’ death, Harry Beckwith formally acquired the entire facility in 1920. His stewardship subsequently heralded another significant series of renovations, in which he installed a saltwater pool, a nine-hole golf course, and bathrooms onto the guestrooms. Interestingly, Beckwith financed the construction of a unique wooden building that took the shape of a ship. Inside resided a bar, a theater, and several dressing rooms. He even changed the name of the whole destination to “Wentworth by the Sea.” But Beckwith eventually sold his interests with the resort to Margaret and James Barker Smith for a sum of $200,000 in the immediate aftermath of World War II. The Smiths continued the renovations started by Beckwith, and even extended the resort’s conference season. As such, the Wentworth by the Sea was allowed to host the Annual Conference for the National Governor’s Association in 1948. But the resort entered yet another period of unstable ownership after the Smiths decided to retire from the hospitality industry in the late 1970s. Failing to find suitable financial support, Wentworth by the Sea closed completely the following decade. The building began to deteriorate significantly as it sat dormant for the next 20 years. At one point, several local officials had even condemned the structure. Fortunately, a group of concerned locals formed the “Friends of the Wentworth” and enlisted the help of the National Trust for Historic Preservation to save the historic resort. The coalition managed to defer the demolition order indefinitely. Then, in 1997, Ocean Properties acquired the Wentworth by the Sea and invested some $30 million into fully restoring the structure back to its former glory. Partnering with Marriott International to manage the refurbished destination, Ocean Properties subsequently reopened the Wentworth by the Sea in 2003. Now once more New Hampshire’s leading coastal resort, the future for the Wentworth by the Sea has never looked brighter.

-

About the Location +

The town of New Castle is actually an archipelago of several islands that reside within the Piscataqua River, with Great Island the largest among them. It was there that the first English settlers arrived way back in 1623, constructing a rudimentary series of earthworks that steadily evolved into a professional fort known as “The Castle.” As the citadel grew in size and sophistication, so too did the surrounding community that supported it. By 1679, the settlement had become large enough to warrant incorporation as a parish of Portsmouth. Its population only continued to grow, allowing for New Hampshire’s colonial governor—Samuel Allen—to formally charter it as a separate town nearly two decades later. The residents decided to call their new town “New Castle” in honor of the neighboring fortress that had recently been renamed as “Fort William and Mary.” It was specifically named for King William III of Great Britain—also known as William of Orange—and his wife and co-monarch, Queen Mary II. They had both assumed the British throne in 1692, following the overthrow of William’s uncle, King James II, during the Glorious Revolution. New Castle soon developed its own prosperous economy that was largely driven by hospitality, maritime trade, and local fishing. And even though New Castle was spread among several different island, a few of its citizens took to agriculture.

Around this time, New Castle was caught up in a strange supernatural controversy that eventually attracted the attention of the powerful Puritan clergy of New England. In 1682, a local tavernkeeper named George Walton reported that his business had become plagued by demons. Those entities had constantly assaulted his tavern by throwing stones and other projectiles, smashing windows and damaging siding. Several prominent clergymen from across the region started to take an interest in the stories, including the great Cotton Mather. Walton’s tales eventually raised an incredible commotion throughout the colonies, even reaching England a few years later. Walton, who was in the midst of a terrible property dispute with his neighbor, accused her of committing acts of witchcraft. Incensed, she, in turn, claimed that Walton was a wizard. The practice of accusing one another of such a crime stemmed from a wider cultural phenomenon that was gripping New England in the late 17th century. Driven by influential religious figures like Cotton Mather, New England’s Puritans ardently believed their communities beset by evil spirits conjured forth at the behest of their neighbors. The mania reached its climax with the Salem Witch Trials further south in Massachusetts Bay Colony. Hundreds of people were eventually accused, with some 18 people hung at the gallows. Colonial officials finally intervened, declaring the trials as unjust. Cases declined dramatically thereafter all across the region, including in places like New Castle.

Fort William and Mary continued to dominate the local landscape, serving as a defensive bulwark against any foreign naval incursion that could attempt to invade New Hampshire. The fort itself was manned completely by colonial militia right up until the eve of the American Revolution. By that point, tensions between the government of King George III and the colonial population of New England were about to foment into open hostilities. The final straw occurred in the fall of 1774, when British soldiers under the command of General Thomas Gage began seizing local stores of gunpowder across the region. Rumors quickly spread that blood had been spilled, resulting in militias from every New England colony to start assembling outside of Boston. Furthermore, several Patriot leaders began relocating their armories to more secured locations. And in some cases, it resulted in limited military actions against official fortifications. On December 14, 1774, a group of Patriots led by John Langdon—a future Founding Father—stormed Fort William and Mary, hoping to capture its supply of ammunition. Severely outnumbered and outgunned, Captain John Cochran and his command of five soldiers surrendered the fort to Langdon’s men. The Patriots subsequently transported the weapons up the Piscataqua River, where they were hidden in the cellar of a Congregational church. The munitions were later used several months later to help reinforce the Patriot army as it attempted to repulse the British at the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Two decades after the American Revolutionary War, Fort William and May was reconstructed and given a new name by Congress—Fort Constitution. It continued protecting the mouth of the Piscataqua River over the next century, undergoing several massive renovations during that time. The fort specifically served as the guard for the Portsmouth Naval Yard as it, too, grew in national importance throughout the 1800s. In the meantime, New Castle remained an isolated fishing village despite the presence of two new bridges that connected it to the mainland. Its character changed dramatically, though, when Daniel Chase and Charles E. Campbell opened the beautiful the Wentworth by the Sea in 1874. It quickly attracted vacationers from all over the Northeast, who enjoyed the Great Island’s cool environment in the summer months. As such, New Castle soon developed a reputation as being an exclusive resort community—one that it has managed to keep well into the present. Fort Constitution is also no longer an active fort, with its last major renovation occurring in 1897 as part of the War Department’s “Endicott Program.” Its guns and accompanying garrison were gradually reassigned to different posts during World Wars I and II, leaving the site a shell of its former self. Fortunately, the federal government protected the ancient citadel by listing it on the National Register of Historic Places in 1963. Like the rest of New Castle, Fort Constitution draws thousands of interested visitors every year.

-

About the Architecture +

When alcohol businessman Frank Jones completely redesigned the Wentworth by the Sea in 1879, he chose the French-inspired Second Empire-style architecture to influence its final appearance. Also known simply as “mansard style,” Second Empire architecture first emerged in Paris at the height of the reign of Emperor Napoléon III. Born Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte, he was the nephew of the legendary Napoléon Bonaparte of the French Revolution. He rose to power by serving as France’s president before making himself its monarch by the middle of the 1800s. Nevertheless, his reign saw a brief restoration in French national pride that was accompanied by a cultural renaissance that affected everything from the arts to the sciences. One the areas that saw this development was architecture. Napoléon III had taken a particular interest with architectural projects at the time, going as far as to commission the complete redesign of Paris’ central cityscape. He subsequently appointed engineer Georges-Eugène Haussmann for the project, instructing the latter to create a new generation of buildings that could accommodate the city’s swelling population. Largely borrowing design elements from the French Renaissance of the 16th century, Haussmann essentially created a brand-new architectural form that soon defined the appearance of Paris. While the project itself only lasted from 1853 to 1870, its impact was felt throughout the world for many years thereafter. Haussmann’s new form quickly appeared across France, as well as many other countries throughout Europe, including Belgium, Austria, and England. Furthermore, the architecture quickly emerged in North America, finding a popular audience in both the United States and Canada. Many hoteliers like Frank Jones saw the fabulous design aesthetics of Second Empire architecture and copied it for their own structures throughout the remainder of the 19th century.

Second Empire architecture was specifically meant for larger structures that could easily showcase its ornate features and grandiose materials. Architects, business owners and other professionals who embraced the form believed that it represented the best of modernity and human progress. This idea especially found an audience in the America, where society was largely perceived to be on an upward path of collective mobility. (In fact, the architecture had become so enmeshed in American society that some took to calling it “General Grant” style.) The form looked similar to the equally popular Italianate-style, in which it embraced an asymmetrical floor plan that was rooted to either a “U” or “L” shaped foundation. The buildings usually stood two to three stories, although some commercial structures—like hotels—exceeded that threshold. Large ornate windows proliferated across the facade, while a brilliant warp-around porch occasionally functioned as the main entry point. The porches would also have several outstanding columns, designed to appear smooth in appearance. Every window and doorway featured decorative brackets that typically sat underneath lavish cornices and overhanging eaves. Gorgeous towers known and cupolas typically resided toward the top of the building, too. Yet, Second Empire architecture broke from Italianate in one major way—the appearance of the roof. Architects always incorporated a mansard-style roof onto the building, which consisted of a four-sided, gambrel-style structure that was divided among two different slopes. Set at a much longer, steeper angle than the first, the second slope often contained many beautiful dormer windows. The mansard roof became a central component to Second Empire architecture after Georges-Eugène Haussmann and his fellow French architects starting using it for their own designs. They had specifically sought to copy the mansard roof of The Louvre, which the renowned François Mansart had created back at the height of the French Renaissance.

-

Famous Historic Guests +

Pascual Cervera y Topete, Admiral in the Spanish Navy at the time of the Spanish-American War (1898)

Jim Folsom, Governor of Alabama (1947 – 1951)

Dan Edward Garvey, Governor of Arizona (1948 – 1951)

Earl Warren, Governor of California (1943 – 1953) and 14th Chief Justice of the United States (1953 – 1969)

William Lee Knous, Governor of Colorado (1947 – 1950)

James C. Shannon, Governor of Connecticut (1947 – 1948)

Walter W. Bacon, Governor of Delaware (1941 – 1949)

Millard Caldwell, Member of the U.S. House of Representatives (1933 – 1941) and Governor of Florida (1945 – 1949)

Melvin E. Thompson, Governor of Georgia (1947 – 1948)

C. A. Robins, Governor of Idaho (1947 – 1951)

Dwight H. Green, Governor of Illinois (1941 – 1949)

Ralph F. Gates, Governor of Indiana (1945 – 1949)

Robert D. Blue, Governor of Iowa (1945 – 1949)

Frank Carlson, Governor of Kansas (1947 – 1950) and U.S. Senator from Kansas (1950 – 1969)

Earle Clements, Governor of Kentucky (1947 – 1950) and U.S. Senator from Kentucky (1950 – 1957)

Jimmie Davis, Governor of Louisiana (1944 – 1948)

Horace Hildreth, Governor of Maine (1945 – 1949)

William Preston Lane Jr., Governor of Maryland (1947 – 1951)

Robert F. Bradford, Governor of Massachusetts (1947 – 1949)

Kim Sigler, Governor of Michigan (1947 – 1949)

Luther Youngdahl, Governor of Minnesota (1947 – 1951)

Fielding Wright, Governor of Mississippi (1946 – 1950)

Phil M. Donnelly, Governor of Missouri (1945 – 1949; 1953 – 1957)

Sam C. Ford, Governor of Montana (1941 – 1949)

Val Peterson¸ Governor of Nebraska (1947 – 1953)

Vail M. Pittman, Governor of Nevada (1945 – 1951)

Charles M. Dale, Governor of New Hampshire (1945 – 1949)

Alfred E. Driscoll, Governor of New Jersey (1947 – 1954)

Thomas J. Mabry, Governor of New Mexico (1947 – 1951)

Thomas Dewey, Governor of New York (1943 – 1954)

R. Gregg Cherry, Governor of North Carolina (1945 – 1949)

Frank Lausche, Governor of Ohio (1945 – 1947; 1949 – 1957) and U.S. Senator from Ohio (1957 – 1969)

Roy J. Turner, Governor of Oklahoma (1947 – 1951)

James H. Duff, Governor of Pennsylvania (1947 – 1951) and U.S. Senator from Pennsylvania (1951 – 1957)

John Pastore, Governor of Rhode Island (1945 – 1950) and U.S. Senator from Rhode Island (1950 – 1976)

Strom Thurmond, Governor of South Carolina (1947 – 1951) and U.S. Senator from South Carolina (1956 – 2003)

Jim Nance McCord, Governor of Tennessee (1945 – 1949)

Beauford H. Jester, Governor of Texas (1947 – 1949)

Herbert B. Maw, Governor of Utah (1941 – 1949)

Ernest W. Gibson Jr., U.S. Senator from Vermont (1940 – 1941) and Governor of Vermont (1947 – 1950)

William M. Tuck, Governor of Virginia (1946 – 1950) and Member of the U.S. House of Representatives (1953 – 1969)

Monrad Wallgren, U.S. Senator from Washington (1940 – 1945) and Governor of Washington (1945 – 1949)

Clarence W. Meadows, Governor of West Virginia (1945 – 1949)

Oscar Rennebohm, Governor of Wisconsin (1947 – 1951)

Lester C. Hunt, Governor of Wyoming (1943 – 1949) and U.S. Senator from Wyoming (1949 – 1954)

Chester A. Arthur, 21st President of the United States (1881 – 1885)

-

Film, TV and Media Connections +

In Dreams (1999)

-

Women in History +

Anne Oakley: Anne Oakley was a renowned sharpshooter who became a pop-culture icon for her marksmanship during America’s Gilded Age. Oakley originally got her start at the age of 15, when she first began performing alongside her partner and future husband, Frank E. Butler. The couple eventually became fixtures of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show for a few years, using the platform to become national celebrities. The impact on Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show proved to be significant, as the circus-like pageant quickly endeared itself among American audiences. It even attracted the attention of several prominent international, including Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom, King Umberto I of Italy, and President François Said Carnot of France. While touring with the company, she even supposedly shot the cigarette out of the mouth of Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm II. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show made Oakley America’s first popular female celebrity. She wound up making more money than anyone else on Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, save for its founder—William “Buffalo Bill” Cody himself. But Oakley also taught thousands of gun-handling lessons throughout her career to interested individuals. Some of those sessions even included a period of time in which she supervised shooting lessons at the Hotel Wentworth’s golf course. Oakley has since become a renowned cultural figure in modern America. Her likeness has been portrayed in countless movies in the years following her death in 1926, including Tall Tales & Legends, Buffalo Girls, and Hidalgo.

Helen Wainwright: Born Helen Sterling, Helen E. Wainwright was a famous Olympian who made a name for herself at the start of the 20th century as a world-class swimmer and diver. At a young age, she was a member of the Women’s Swimming Association of New York, getting coached by the great Louis de B. Handley. Handley and other experts quickly noticed Wainwright’s speed in the water and implored her to compete in national tournaments held throughout the United States. In just a matter of years, Wainwright had won 17 gold medals for swimming as well as two others for diving. Still just a teenage, she also started completing on the world stage! Wainwright won the silver medal in the women’s three-meter springboard competition in 1920, as well as the silver in the women’s 400-meter freestyle event four years later in Paris. But perhaps the greatest moment of her swimming career came in 1922, when she set an Olympic record for speed in completing the women’s 1500-meter freestyle event! Additional highlights of her inspiring life involved nearly becoming the first woman to swim across the English Channel and hosting a series of popular swimming demonstrations at the New York Hippodrome. She even hosted swimming classes at the Wentworth by the Sea. In some cases, she gave special demonstrations for guests in the saltwater pool that Harry Beckwith created during his tenure as owner. Wainwright eventually ended her career serving as a popular swimming coach onboard a series of cruise liners that operated out of her native New York City. Passing away in 1965, the International Swimming Hall of Fame inducted her into its organization posthumously several years later.

Guest Historian Series

Read Guest Historian SeriesNobody Asked Me, But…

Hotel History: Wentworth By The Sea (1874), New Castle, New Hampshire

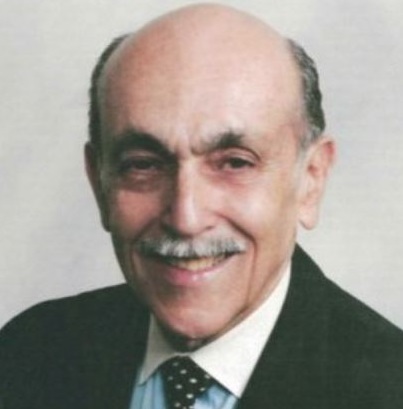

By Stanley Turkel, CMHS

The Wentworth by the Sea (formerly the Hotel Wentworth), built in 1874 by Daniel E. Chase and Charles E. Campbell, was the largest wooden structure on the New Hampshire coast. It was bought in 1879 by Frank Jones, wealthy owner of banks, breweries, insurance companies, racing stables, railroads and the world's largest shoe-button company. Jones hired the talented Frank W. Hilton (no relation of Conrad) to manage and promote the Wentworth. Hilton introduced steam-driven elevators, Western Union telegraph, a telephone wire connected to the Rockingham Hotel, high-tech outdoor electrical arc lights, flush water closets, a dish-washing machine, croquet and lawn tennis, billiard room, bathing houses, athletic competitions, horses and an in-house orchestra. With Frank Jone's death in 1902, the hotel was sold but didn't have another successful owner until Harry Beckwith bought the Wentworth in 1920 and operated it for 25 years.

In 1905, the hotel housed the Russian and Japanese delegations who negotiated the treaty of Portsmouth to end the Russo-Japanese War. President Theodore Roosevelt proposed the peace talks and won the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts. Frank Jones's executor, Judge Calvin Page followed his will and the Wentworth provided free accommodations to both delegations. After the final document was signed at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, the Japanese hosted an "International Love Feast" at the Wentworth.

In 1916, the famous 56 year-old Annie Oakley was persuaded by Manager Harry Priest to demonstrate her horsemanship and shooting skills for guests at the Wentworth. Two sports, golfing and swimming, sum up the Beckwith focus. He hired the famous Donald Ross to design the finest nine-hole course in New England. Beckwith built the Ship, a massive new building shaped like a cruise liner and located between the bridge to Rye and the hotel pier. He also created a deep ocean-fed pool with a new cement floor. In accordance with the racist fabric of America, Beckwith promised his guests that they would receive the finest in gentile-only accommodations. The Wentworth prospered through Prohibition and survived even the Great Depression but was closed during World War II when the military took over the hotel's facilities for the duration.

In 1946, the Wentworth was acquired by Margaret and James Barker Smith who provided hands-on and enlightened management for 34 years until 1980. Over those years, they focused on entertainment, masquerades, Mardi Gras celebrations, photographs of guests, tennis, fresh seafood, expansion of the golf course to 18 holes, a new modern Olympic-sized pool, expansive new floral plantings, etc. Many celebrities visited the Wentworth: Zero Mostel, Jason Robards, Colonel Sanders and Frank Perdue, Vice President Hubert Humphrey, Ralph Nader, Ted Kennedy, Herbert Hoover, Margaret Chase Smith, Shirley Temple, Richard Nixon, Milton Eisenhower and John Kenneth Galbraith, among many others. On July 4, 1964, Emerson and Jane Reed became the first African Americans to overcome the hotel's long-standing segregation policy by dining at its restaurant.

By the mid-1970s, both the Wentworth and the Smiths were aging and deteriorating. In the fall of 1980, after thirty-four consecutive summers, the Smiths sold the hotel to a Swiss conglomerate, the Berlinger Corporation who tried without success to keep the Wentworth running year-round. Finally Henley Properties, the fourth owner in seven years, bulldozed eighty-five percent of the "newer" buildings and gutted the oldest portion of the hotel down to its wooden studs. With declining fortunes and changing owners, the Wentworth closed in 1982. After plans for its demolition were announced, it appeared on the National Trust for Historic Preservation's list of Americas Most Endangered Places and the History Channels America's Most Endangered.

In 1997, Ocean Properties acquired the Wentworth by the Sea and, after extensive renovation and restoration, reopened in 2003 as a Marriott resort. The hotel is a member of the National Trust for Historic Preservation and Historic Hotels of America.

*****

About Stanley Turkel, CMHS

Stanley Turkel is a recognized consultant in the hotel industry. He operates his hotel consulting practice serving as an expert witness in hotel-related cases and providing asset management an and hotel franchising consultation. Prior to forming his hotel consulting firm, Turkel was the Product Line Manager for worldwide Hotel/Motel Operations at the International Telephone & Telegraph Co. overseeing the Sheraton Corporation of America. Before joining IT&T, he was the Resident Manager of the Americana Hotel (1842 Rooms), General Manager of the Drake Hotel (680 Rooms) and General Manager of the Summit Hotel (762 Rooms), all in New York City. He serves as a Friend of the Tisch Center and lectures at the NYU Tisch Center for Hospitality and Tourism. He is certified as a Master Hotel Supplier Emeritus by the Educational Institute of the American Hotel and Lodging Association. He served for eleven years as Chairman of the Board of the Trustees of the City Club of New York and is now the Honorary Chairman.

Stanley Turkel is one of the most widely-published authors in the hospitality field. More than 275 articles on various hotel subjects have been posted in hotel magazines and on the Hotel-Online, Blue MauMau, Hotel News Resource and eTurboNews websites. Two of his hotel books have been promoted, distributed and sold by the American Hotel & Lodging Educational Institute (Great American Hoteliers: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry and Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels East of the Mississippi). A third hotel book (Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels in New York) was called "passionate and informative" by the New York Times. Executive Vice President of Historic Hotels of America, Lawrence Horwitz, has even praised one book, Great American Hoteliers Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry:

- “If you have ever been in a hotel, as a guest, attended a conference, enjoyed a romantic dinner, celebrated a special occasion, or worked as a hotelier in the front or back of the house, Great American Hoteliers, Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry is a must read book. This book is recommended for any business person, entrepreneur, student, or aspiring hotelier. This book is an excellent history book with insights into seventeen of the great innovators and visionaries of the hotel industry and their inspirational stories.”

Turkel was designated as the “2014 Historian of the Year by Historic Hotels of America,” the official program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. This award is presented to an individual for making a unique contribution in the research and presentation of history and whose work has encouraged a wide discussion, greater understanding and enthusiasm for American History.

Works published by Stanley Turkel include:

- Heroes of the American Reconstruction (2005)

- Great American Hoteliers: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2009)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels in New York (2011)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels East of the Mississippi (2013)

- Hotel Mavens: Lucius M. Boomer, George C. Boldt and Oscar of the Waldorf (2014)

- Great American Hoteliers Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2016)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels West of the Mississippi (2017)

- Hotel Mavens Volume 2: Henry Morrison Flagler, Henry Bradley Plant, Carl Graham Fisher (2018)

- Great American Hotel Architects Volume 1 (2019)

- Hotel Mavens Volume 3: Bob and Larry Tisch, Curt Strand, Ralph Hitz, Cesar Ritz, Raymond Orteig (2020)

Most of these books can be ordered from AuthorHouse—(except Heroes of the American Reconstruction, which can be ordered from McFarland)—by visiting www.stanleyturkel.com, or by clicking on the book’s title.