Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

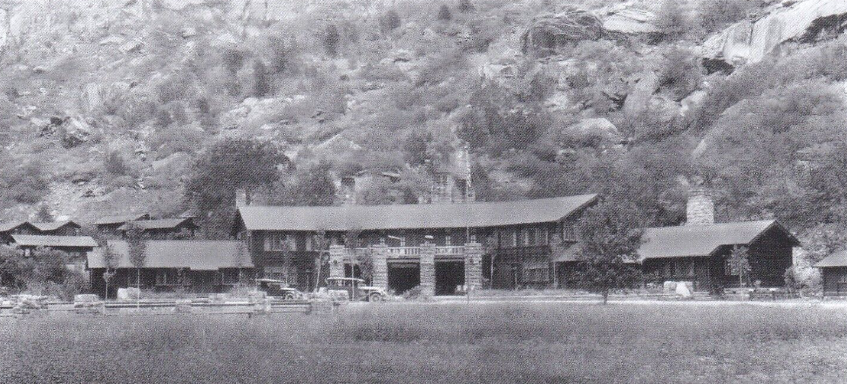

Discover Zion Lodge, which displays some of the finest National Park Service Rustic-style architecture in the country.

Situated right in the heart of Zion National Park, the historic Zion Lodge actually originated from a compromise between the Union Pacific Railroad and the National Park Service during the early 20th century. Similar to other railroads from the period, the Union Pacific desired to construct hotels along its various routes in order to attract new customers. Among the railways it wanted to highlight was one that traversed past Cedar City in southwestern Utah. After months of negotiations, the company eventually managed to broker a deal with the National Park Service to build a luxurious hotel in Zion National Park as an official concessionaire. (To its end, the federal government welcomed the partnership as a way to generate greater national interest in the newly created national park.) Construction did not commence right away though, since the two sides could not agree on the size of the building. The Union Pacific Railway and its lead architect, Gilbert Stanley Underwood, strongly advocated for the creation of a massive structure. Indeed, Underwood’s initial design compositions utilized the similar grandiose detailing that he had employed for other building in Grand Canyon and Bryce Canyon National Parks. But upon reviewing the company’s blueprints, Stephen Mather—the Director of the National Park Service—insisted the prospective building be much smaller in scale to better complement the park’s tranquil setting.

Despite their disagreements, the two camps ultimately settled on a building that would have a medium frame. Furthermore, Underwood modified his design to place an additional series of rustic cabins around the hotel that would offer overflow housing for guests. With a plan firmly in place, Underwood and his team began constructing the new building in 1924. The project nonetheless proved to be a massive undertaking, requiring a wealth of resources to complete. In fact, Underwood had to distribute some 250,000 board feet of lumber into Zion Canyon via a wire and pulley tramway called the “Cable Mountain Draw Works.” (The remnants of the Cable Mountain Draw Works still exist in Zion National Park and can be visited by guests.) But when the construction finally concluded a year later, the new “Zion Lodge” stood as an engineering marvel. Indeed, its architectural appearance served as a brilliant architectural example of a unique style that would eventually become known as “National Park Service Rustic.” Now list in the U.S. National Register of Historic Places, Zion Lodge has since emerged as one of the best places to stay throughout the whole region. Cultural herniate travelers are certain to enjoy experiencing its amazing amenities, beautiful views, and fascinating institutional history. (Zion Lodge was inducted into Historic Hotels of America in 2012.)

-

About the Location +

Located in the Virgin River Valley of southwestern Utah, the area that now constitutes Zion National Park has a fascinating story. Generations of Native Americans originally occupied the region, living as hunters and gatherers for many millennia. They specifically inhabited dozens of small villages known as “pueblos,” which were surrounded by fields of corn and other distinctive crops. Among the most noteworthy Native American people to call the land home were the Anasazi, otherwise remembered as the “Basketmakers” for their unique archeological record. However, the climate of the greater Virgin River Valley changed dramatically over the course of the 11th and 12th centuries, becoming more hostile to largescale permanent settlements. Human activity in the region was thus seasonal and sporadic over the next several centuries, even after the first European explorers began arriving in the late 1700s. But in 1847, a few Mormon families decided to establish farms and ranches near the banks of the Virgin River. Naming the area as “Kolob,” the Mormons proceeded to rely upon the valley for its abundant natural resources. Indeed, Zion National Park’s northern borders were usually visited for its wealth of timber and mineral deposits. Moron communities continued expanding and eventually reached the heart of the future Zion National Park during the height of the American Civil War. In fact, one Mormon farmer named Isaac Behunin even created a homestead at the bottom of Zion Canyon in 1863! (Many historical sources claim that Behunin gave the region the title “Zion” around the same time.)

The area’s metamorphosis into a prominent tourism destination began not long thereafter, as several conservationists started examining the region throughout the Gilded Age. Their studies soon spread to a wider American audience, generating immense national interest in its beauty. Perhaps the climax of this popularity occurred following the debut of Frederick S. Dellenbaugh’s paintings of Zion Canyon at the St. Louis World’s Fair. Attempts to safeguard the region’s tranquil landscape quickly gained momentum, which eventually led President William Howard Taft to declare it a National Monument in 1909. President Woodrow Wilson then further aided in the site’s conservation, signing a law several years later that transformed the area into Zion National Park. Under the direction of the nascent National Park Service, the federal government and its corporate partner, the Union Pacific Railroad, then initiated a series of expansive infrastructure projects to enhance the location’s accessibility. A multitude of new trails and roads opened across the region, helping to spur travel to Zion National Park after World War I. Additional improvements to the park infrastructure appeared over the course of the next two decades, including more trails, roads, and a special hotel known as “Zion Lodge.” Perhaps the greatest engineering marvel to debut within the park was the new Zion—Mount Carmel Highway and its 1.1-mile-long tunnel. Carved deep into the interior of Mount Carmel, the tunnel featured a series of masterfully cut galleries that offered motorists a fantastic view of Zion National Park.

Today, Zion National Park remains one of the National Park Service’s most iconic destinations, with some 5 million people visiting every year. Much of this visitation is driven by the wealth of fantastic natural landmarks that reside throughout the park, which form a majestic, memorable landscape. Situated within the center of the park is the magnificent Zion Canyon—a sprawling, picturesque gorge that winds along a fork of the Virgin River for 16 miles. The canyon ultimately ends near a resplendent natural amphitheater known as the “Temple of Sinawava,” as well as a beautiful cavern referred to as “The Narrows.” But the canyon itself is filled with countless hiking trails that lead to a variety of breathtaking geological wonders, including The Subway, the Emerald Pools, and the Kolob Arch. Zion National Park features numerous iconic mountains, too, such as Tucupit Point, the Towers of the Virgin, and the Court of the Patriarchs. One of the most popular peaks to explore among contemporary travelers is Angels Landing. Standing 1,500 feet in height, Angels Landing is a rock formation that features a renowned pathway cut straight through its façade. (Many guests enjoy exploring those fantastic sites via the equally historic Zion—Mount Carmel Highway, which is listed in the U.S. National Register of Historic Places.) But other guests enjoyed discovering the unique flora and fauna inside Zion National Park. The area specifically serves as the habitat for around 400 species of wildlife alone, making Zion National Park one of the most unique ecosystems in the whole continental United States!

-

About the Architecture +

Zion Lodge and its attending cabins stand today as brilliant examples of National Park Service Rustic architecture. As the name would suggest, the form first became prominent in the United States before it spread throughout the rest of North America. Architect Herbert Maier was central toward conceptualizing the aesthetic while he was studying the Arts and Crafts movement at the University of California, Berkeley, in the early 20th century. Rejecting the design aesthetics of industrialized society, Maier created an architectural form that utilized building materials to better connect a structure to its natural surroundings. Following his graduation from school, he quickly set about designing several buildings with his novel architectural approach. Maier found a particularly receptive audience at the National Park Service, as many alumni had graduated from the University of California, Berkeley around the same time. Other architects—such as Mary E.J. Colter and Gilbert Stanley Underwood—mimicked Maier’s mentality and contributed their own variations to the style. Indeed, the synthesis of many unique interpretations helped create a cohesive form that soon became widespread throughout the country. Many state governments particularly embraced the eclectic design philosophy, using the aesthetic to create all kinds of public structures within their own park systems. Even the National Park Service began utilizing the form for its official construction projects, eventually making the architectural style synonymous with the organization itself! National Park Service Rustic reached the height of its popularity when the Civilian Conservation Corps began erecting dozens of new park structures during the 1930s. But its interest had waned by the middle of the century though, as architects looked to newer design philosophies. Nevertheless, National Park Service Rustic endured to become one of America’s most distinctive and historic architectural styles.