Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

the glasbern inn history

Discover Glasbern, a picturesque and historic hotel in Pennsylvania tucked away in the Lehigh Valley pasturelands.

Glasbern is a picturesque Pennsylvania hideaway, hidden away amid the swaying grasses and open vistas of the Lehigh Valley pasturelands. Spread across 150 acres, this amazing holiday destination was once a historic farm that first opened shortly following the end of the American Revolutionary War. The war itself had left a profound impact on the surrounding area, for Patriots relied upon the valley to support George Washington’s army. In 1787, a farmer by the name of Melchior Siep acquired the tract of land and transformed it into a prosperous homestead. Siep actually opened his farm a full decade before the community of Fogelsville came into existence! The neighboring settlement of Allentown—then known as “Northampton Towne”—was still largely defined by its immigrant German population, who had flooded the valley with the promises of religious tolerance and affordable land grants throughout the 18th century. Glasbern had watched as the countryside evolved from being a community of sustenance farmers to a manufacturing powerhouse. Over the course of the 19th century, the Lehigh Canal and the Lehigh & Susquehanna Railroad ushered forth a new era of economic expansion. The evolution of local transportation incentivized enterprising businessmen from Philadelphia to relocate their businesses to the Lehigh Valley. By the time of the American Civil War Allentown and its neighbors were filled with countless factories, plants, and warehouses. In fact, Allentown featured several prominent industries that were necessary to advance the Union war effort. One such merchant, Henry Leh, grew his small shop into a prominent footwear company due to the exclusive contracts he obtained from the federal government.

Industry kept arriving to Allentown, which saw segments of the surrounding countryside filled with new industrial complexes. Nevertheless, Fogelsville retained its serene, pastoral atmosphere, as it continued to host various homesteads like it originally did over a century ago. By this point, Joel Mohr had come to own Glasbern, constructing the current iteration of the homestead in 1870. It was this fantastic structure that would serve as the main building for the resort today. Glasbern remained in private hands for many generations until it was left abandoned upon the death of its last owner, William Kirschner, in the 1970s. Determined to save the location from oblivion, Al and Beth Granger purchased the entire site with the intent on renovating it into a secluded vacation retreat. After thoroughly reconstituting the facility into a quaint country getaway, the debuted the destination for the first time in 1985. All of Glasbern’s historic structures debuted as part of the new destination. With the caring touch of master carpenters, the original tractor shed became the Carriage House and the garage was transformed as the Gate House. The Grangers also installed a wealth of additional facilities onto the grounds, including the stables and the Packhouse. Both structures were historic in origin, too, having been disassembled and transported from other farms. But their construction did more than just convert the homestead—it also wonderfully preserved the brilliant architecture that its previous tenants developed many years prior. The couple even revitalized Glasbern’s horticultural past by restarting much of its prior farming activities. Now a member of Historic Hotels of America, the Glasbern is one of the most luxurious places to stay in the greater Lehigh Valley.

-

About the Location +

The quaint village of Fogelsville resides in the heart of Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley, which is just an hour north of Philadelphia. Its specifically located only a few miles outside of the historic community of Allentown, although the towns of Bethlehem and Easton are close nearby, too. Native American of the Lenni Lenape (or Delaware) tribe first inhabited the region centuries ago, using the land to hunt and fish. It was densely wooded at the time, preventing the Lenni Lenape from erecting massive settlements throughout the area. But in the early 1700s, Europeans began to arrive north from the banks of the Delaware River to trade. The Europeans began to stay permanently in increasing numbers, clearing the land and constructing sustenance farms. Most of the earliest transplants were Germans, soon to be known as the “Pennsylvania Dutch.” They were initially attracted to Pennsylvania Colony based on William Penn’s promises of religious tolerance and generous real estate prices. Soon enough, the German migrants had created a vibrant agricultural society that spanned the entire valley. The Penns themselves had interests in the area, as the family had expanded its landholdings into the region during the 1730s. They, in turn, assigned the warrant to the land to Joseph Turner, a wealthy merchant from Philadelphia. On their behalf, Turner sponsored several surveys throughout the area, and sponsored the creation of various towns to support the valley’s emerging farms. Easton, in particular, was perhaps the greatest settlement project at the time, for the Penns specifically set aside some 1,000 acres for its creation in 1739.

Eventually, Turner sold some 5,000 acres of the Penns’ territory to his business partner, William Allen, in 1735. Allen himself was a prominent resident in the colony, serving at times as the Mayor of Philadelphia and Chief Justice for Pennsylvania. He subsequently began developing area some five years later, building a small log cabin along a tributary of the Lehigh River called “Jordan Creek.” He mainly used that rustic structure to serve as an outdoor lodge that hosted the likes of Pennsylvania’s colonial governor John Penn. Allen also deeded 500 acres at the confluence of Monocacy Creek and Lehigh River to a sect of German Protestants known as the Moravians. A missionary group led by David Nitschmann and Count Nicolaus Zinzendorf then traveled to the region on Christmas Eve in 1741, a founded a church that would serve as the nucleus for the future town of Bethlehem. As more families traveled north to settle the valley, Allen decided to found his own town to serve them. Yet, many historians speculate that his personal rivalry with the Penn family in the area spurred his motivation to sponsor the creation of his own town. In fact, Allen yearned for his new settlement to supplant the Penn-backed Town of Easton as the valley’s main cultural and commercial center. Interestingly, Allen initially called the new settlement “Northampton Towne” after Northampton County in 1762. His plan for the community called for the creation of 42 blocks separated into 756 separate lots. Every single one of the original streets were named after his children, as well as the influential figures who had directly impacted his life. When Allen passed away in 1767, his son, James, inherited the family property in and around Northampton Town. He even constructed a brilliant summer home in the center of his father’s town, calling it “Trout Hall.”

Lehigh Valley became caught in the middle of the American Revolution, as Tories and Patriots marshaled against one another. Northampton Towne became a hotbed of patriotic sentiment, as a Committee of Observation roamed the streets and pressured neighbors loyal to the British Crown out of the community. Several armed militias soon formed, which started drilling in the hills just outside of town. Northampton Towne also featured a hospital at the corner of James and Hamilton Streets for wounded and sick soldiers from the Continental Army. Hessian prisoners also called the area home for a while following the Battle of Trenton in 1777, housed within a small house in the vicinity of Gordon Street. Northampton Towne even hosted a paper cartridge factory that manufactured munitions for muskets used by American forces. It had relocated to Northampton Town following the rise of Toryism in neighboring Bethlehem. The factory was later joined by a group of 16 armorers, who opened a shop along Little Lehigh Creek for the repair of weapons and materials. But perhaps the town’s greatest contribution to the patriot cause was its involvement in concealing the famous Liberty Bell from British troops during the conflict. Following the defeat of Washington’s army at the Battle of Brandywine, state official of the new Commonwealth of Pennsylvania sought to remove the Liberty Bell—as well as 10 other similar objects—from Philadelphia. They feared that the British would arrive and melt down each bell into musket balls. As such, two teamsters, John Snyder and Heinrich Bartholomew, hurriedly transported the Liberty Bell to Northampton Towne, where they hid it in the basement of the Old Zion Reformed Church. Today, a local shrine commemorating the event is located in the basement of the structure.

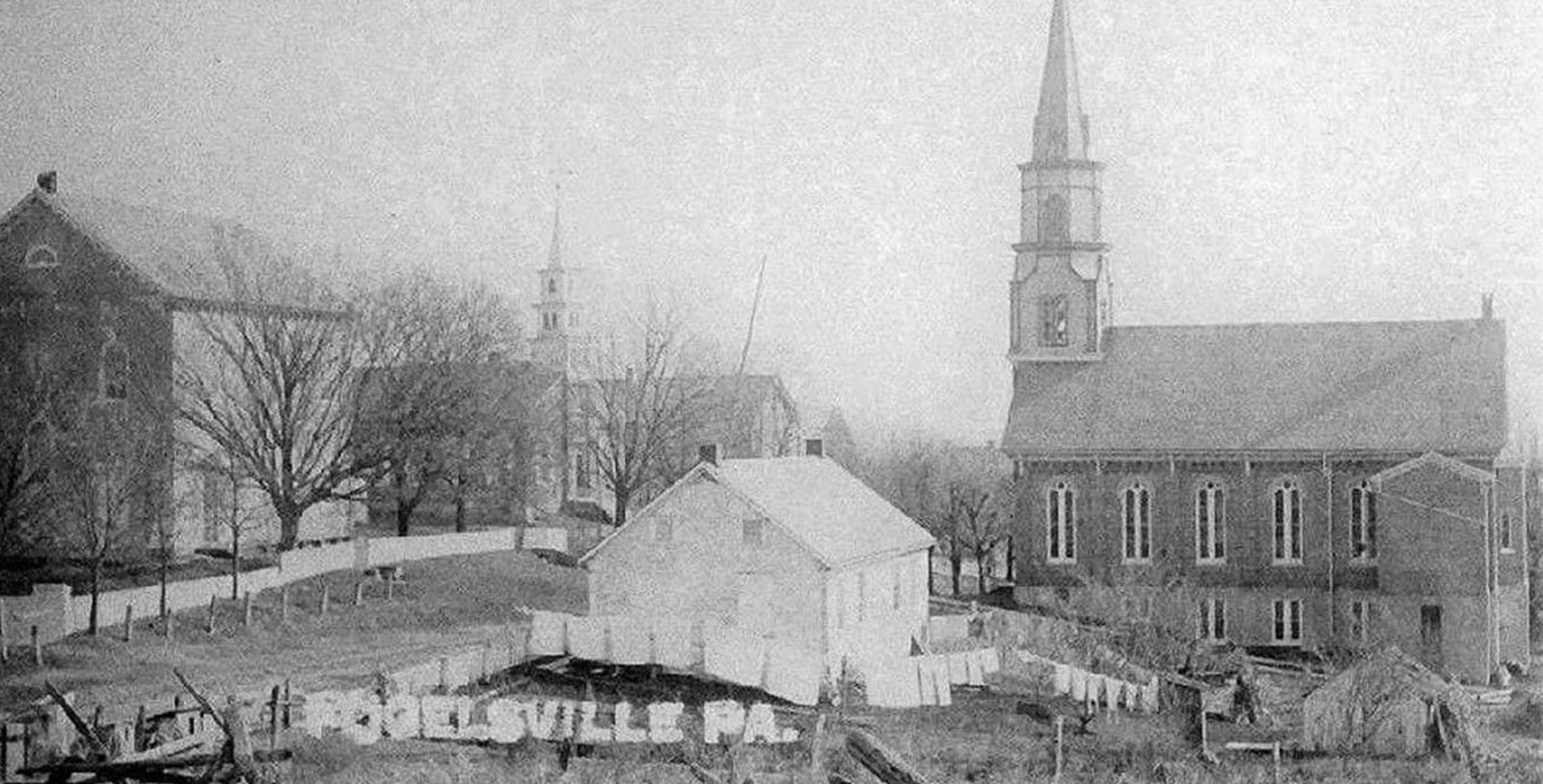

Following the American Revolution, Northampton Towne grew slowly and remained a largely pastoral settlement. Many people in the region still spoke some dialect of German as their primary language. It was around this time, though, that the village of Fogelsville came into existence, when Judge John Fogel opened a hotel in the area in 1798. Enough people had moved into Northampton Towne that by the early 1800s, it was able to host its own post office. The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania then formally incorporated it in 1811, before making it the seat for the new Lehigh County a year later. But the area’s remote character changed forever, after the Lehigh Navigation Company constructed a navigable for the transportation of coal in 1829. Known as the Lehigh Canal, it played a significant role in transforming the entire Lehigh Valley into a center for regional commerce. The canal was eventually replaced as the preferred method of transporting goods through the area in 1855, when the Lehigh & Susquehanna Railroad arrived. All the while, Northampton Towne evolved into a vibrant market community. All sorts of storefronts and banks began appearing within its downtown district, forming a unique commercial identity that it had not experienced before. The residents had even begun calling it “Allen’s Town” or “Allentown,” too. Use of the name had become so common that the town’s name was officially changed to “Allentown” in 1838.

This economic proliferation continued despite the outbreak of the American Civil War in the mid-19th century. In fact, the conflict itself had created several prominent industries that fueled the federal war effort, including brick yards, shoe factories, and flour mills. The Allentown Paint Company also opened during the war, as did the Allentown Rolling Mill Company. Local footwear outfitter Henry Leh was even able to grow his business into a massive department store due to the exclusive contracts his received to supply the Union Army. But even more industries appeared in Allentown in the later-half of the 19th century and well into the 20th. Silk manufacturing became the dominant economic forced in Allentown for decades. Starting with the Phoenix Manufacturing Company in 1886, Allentown had grown to host some 26 different mills by the 1920s. This number increased exponentially to 85 when the silk producers began to use rayon. While the silk industry emerged in force, Jack and Gus Mack relocated their own business—Mack Trucks—to Allentown from their native Brooklyn. Moving into a recently vacated industrial complex at on South 10th Street, the two began constructing some of the most reliable trucks ever made in American history. Western Electric also established a plant in Allentown at the end of World War II, which created the world’s first mass-produced transistor. Today, both Allentown and the other communities of the greater Lehigh Valley retain much of their historic charm. As such, they constitute some of the best places to visit for a historic experience in all of Pennsylvania.

-

About the Architecture +

When John Mohr first began constructing the current iteration of Glasbern back in 1870, he relied specifically upon the design principles of Colonial Revival-style architecture. Colonial Revival architecture today is perhaps the most widely used building form in the entire United States. It reached its zenith at the height of the Gilded Age, where countless Americans turned to the aesthetic to celebrate what they feared was America’s disappearing past. The movement came about in the aftermath of the Centennial International Exhibition of 1876, in which people from across the country traveled to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to commemorate the American Revolution. Many of the exhibitors chose to display cultural representations of 18th-century America, encouraging millions of people across the country to preserve the nation’s history. Architects were among those inspired, who looked to revitalize the design principles of colonial English and Dutch homes. This gradually gave way to a larger embrace of Georgian and Federal-style architecture, which focused exclusively on the country’s formative years. As such, structures built in the style of Colonial Revival architecture featured such components as pilasters, brickwork, and modest, double-hung windows. Symmetrical designs defined Colonial Revival-style façades, anchored by a central, pedimented front door and simplistic portico. Gable roofs typically topped the buildings, although hipped and gambrel forms were used, as well. This building form remained immensely popular for years until largely petering out in late-20th century. Nevertheless, architects today still rely upon Colonial Revival architecture, using the form to construct all kinds of residential buildings and commercial complexes.