Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

Discover Fairmont Olympic Hotel, which is located on the grounds of the first campus of the University of Washington in Downtown Seattle.

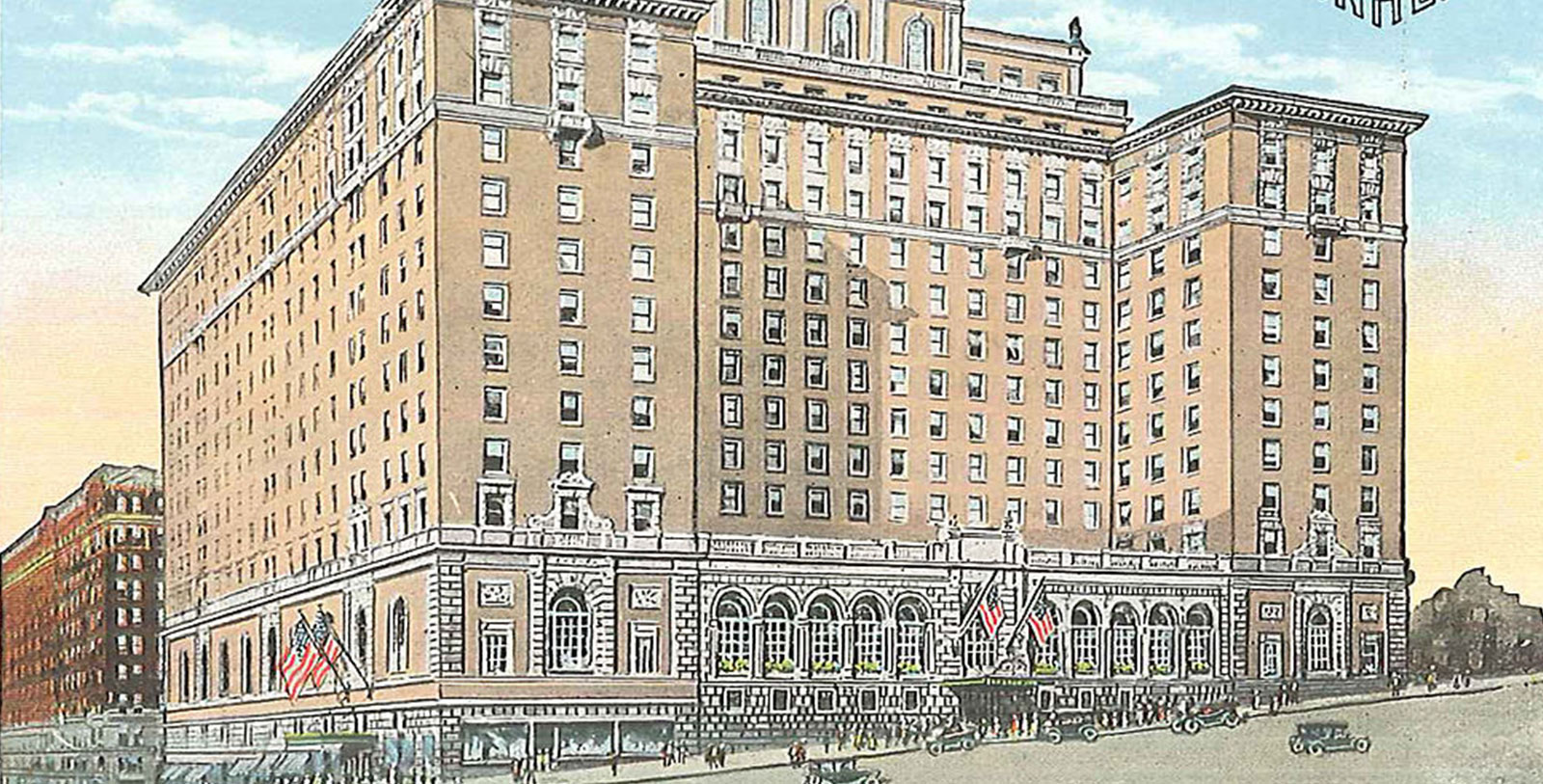

Fairmont Olympic Hotel, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2018, dates back to 1924.

VIEW TIMELINEListed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places, the Fairmont Olympic Hotel is among Seattle’s most celebrated holiday retreats. Its origins harken back to the early 20th century, when the local Chamber of Commerce set into motion a plan to build a magnificent boutique hotel. After years of looking for the perfect place to construct the new building, the Chamber of Commerce decided to use a four-block area known as the “Metropolitan Tract.” The area had belonged to the University of Washington since 1861, even after it had relocated to a campus north of Portage Bat some four decades later. Representatives from both the Chamber of Commerce and the University of Washington spent several months negotiating the terms upon which to lease the land. In 1904, the schools’ regents eventually agreed to give access to the Metropolitan Building Company with the stipulation that final ownership rights fell to the university. But tensions rose between the two parties, as the University of Washington expressed concerns about the security of its position. Nevertheless, the Chamber of Commerce and the Metropolitan Building Company subleased the location to the Community Hotel Corporation in order to start the building project in earnest.

Starting in the early 1920s, the Community Hotel Corporation proceeded to raise funds to construct the new business through an ambitious public bonds drive. Led by W.L. Rhodes and Frank Waterhouse, the campaign raised $3 million worth of bond money. As such, the endeavor soon became a community-based enterprise, with a fair distribution of public and private funds fueling the project. At the same time, The Seattle Times held a contest to find a name of the building. Receiving nearly 4,000 applications, the newspaper’s committee settled on “The Olympic.” Construction finally began in earnest in 1923, when the Community Hotel Corporation broke ground on the Metropolitan Tract. The designs for the new hotel were crafted by the renowned New York-based architectural firm George B. Post & Sons, which had been hired by the Community Hotel Corporation a year earlier. The Community Hotel Corporation also contracted with Frank A. Dudley and Roy Carruthers to begin organizing the hotel’s future business operations, which they did through their own business, the Olympic Hotel Company. Yet, the company had come to desire an even larger, more spectacular hotel and raised an additional $1.65 million for its expansion. The contractors eventually raised the building’s impressive steel frame in early 1924, with construction wrapping up in its entirety by the end of the year. In the end, it eventually took some $5.5 million to build The Olympic, including the cost to fully furnish the structure.

Neary 2,000 people arrived when the hotel debuted in downtown Seattle in December 1924. As guests entered the building they were absolutely awe-struck by what they encountered. Beautiful buff-faced brick and terra cotta trim lined the walls, while bases of granite and Belgian marble constituted the floor. Spectacular American oak filled the grand lobby, which featured such renowned facilities like a reception desk and a telegraph room. Several private storefronts and telephone booths occupied the space, as well. Some of the most fabulous venues in Seattle were located at The Olympic, too, including the Palm Roo, Assembly Lounge, and The Georgian. As such, The Olympic rapidly emerged as Seattle’s most exclusive destination. Popularity with the hotel had surged so much that its managerial team decided to add another wing of accommodations in 1928. The Olympic had even begun to cultivate a national audience, as several U.S. Presidents—starting with Herbert Hoover—stayed at one point or another. Yet, this prosperity was not to last, as the Great Depression significantly destroyed the city’s economy. William Edris then began managing The Olympic during World War II and guided the business back to relevance. The Olympic itself was heavily involved in the war effort, hosting various War Bonds rallies to support the troops.

The University of Washington still retained ultimate control over The Olympic by the beginning of the 1950s. But its regents had come to openly embrace the hotel. To make the business even more profitable, it reached an agreement with Westin Hotels and Resorts to manage The Olympic on its behalf in 1955. The prestige of business remained intact, though, as it continued to host the most illustrious guests from across the nation. Several renowned figures made regulars appearances at the hotel, including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Bing Crosby, Joan Crawford, and John Wayne. Senator Warren G. Magnuson used the hotel as his private residence in Seattle whenever he was not stuck in Washington D.C. And its tradition of hosting U.S. presidents continued, too, hosting the likes of Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, and Lyndon B. Johnson inside its illustrious Presidential Suite. Despite changing hands several times in the late 20th century, The Olympic remained one of Seattle’s most sought-after vacation hotspots. Today, hotel is operated by Fairmont Hotels and Resorts as the “Fairmont Olympic Hotel.” Although no longer owned by the University of Washington, this wonderful historic destination continues to provide world-class hospitality and comfort. Few places in the country can match the outstanding elegance and fascinating historical character of the Fairmont Olympic Hotel.

-

About the Location +

The founding of Seattle dates to 1851, when nearly two dozen Euro-American migrants arrived from Illinois to settle Alka Point. Led by Arthur A. Denny, those pioneers are known to history as the “Denny Party.” Their small community was the first non-Native American settlement in region, which primarily harvested timber from the surrounding forest. Yet, the water surrounding Alki Point proved to be too shallow to accommodate the commercial vessels that transported the lumber. As such, the pioneers relocated a few miles to the north along Puget Sound, specifically at the mouth of the Duwamish River near Elliot Bay. Shortly thereafter, those settlers were joined by another group under the direction of David Swinson Maynard, who many referred to as “Doc.” Maynard’s group set up just south of the Denny Party, and over time, those two communities melded together. Right next to the village was a vibrant community of local Duwamish Indians who were governed by a Chief Seattle. The two groups formed a close bond that proved to be beneficial over the next decade. In honor of the chief, the pioneers eventually called their settlement as “Seattle.” The name stuck, even after the Territorial Legislature formally incorporated the community in 1869.

Logging remained the dominant industry within the community, with a steam-powered sawmill serving as its main employer. The village grew slowly at first, with European immigrants from America’s East Coast constituting the majority of the new arrivals. Yet, the community’s population exploded when the Northern Pacific Railway arrived in nearby Tacoma. This development was further augmented when a second railroad—the Great Northern Railway—established an actual terminus within the city limits. As such, Seattle’s population rose from around 3,500 in 1880 to more than 80,000 some two decades later. The railroads also transformed the city into a major hub for trade in the western United States, rivaling the likes of San Francisco in its commercial importance. Some 50 miles of wharves emerged in the heart of Seattle, too, which turned the area into a bustling seaport. The development of its waterfront even caused countless miners to use it as their main supply depot for the Klondike Gold Rush of the 1890s. Its metamorphosis into an international trading center spawned rapid urbanization, as all sorts of businesses quickly appeared for the first time. Seattle, in particular, earned a reputation for being an “open city,” in which saloons, brothels, and casinos dominated the local landscape.

As the Seattle evolved more into a modern city, its politicians became increasingly concerned about its fate. Several activists within the early 20th-century Progressive Movement eventually drove out the officials who embraced the “open city” policies. In their wake, they instituted strict prohibitions against alcohol and other vices through the 1930s. But the progressives also made headways in such arenas like housing and women’s suffrage. The Progressive Movement in Seattle ebbed right when the Great Depression hit, which affected its economy significantly. The city was able to lift itself out of the financial slump, thanks in large part to the expansion of the Defense industry in the years leading up to World War II. Seattle was a key manufacturer for the American war effort, producing all kinds of matériel for the military. The city itself was home to several major defense contractors, too. The greatest among those company was Boeing, which created thousands of planes at its Seattle and Renton factories. Another business—the Seattle-Tacoma Shipbuilding Corporation—employed some 33,000 people, who churned out countless ships during the war. At the same time, the city’s demographics had changed considerably. Large numbers of African Americans arrived in Seattle, allured by the prospects of work in the new factories. Japanese Americans began immigrating to the city, as well, although the wartime policies the Roosevelt administration temporarily relocated them to internment camps hundreds of miles away in Idaho.

By the late 20th century, Seattle had become one of the most economically vibrant destinations in the world. Supplementing this growth was the emergence of several prominent technological firms. Many high profile names within the industry established a significant presence in the city, such as Amazon, Microsoft, and Nintendo of America. Those businesses attracted talent from around the world, which saw Seattle’s population grow to two million people by the 1990s. The infusion led to a cultural proliferation that saw Seattle become a center for art and knowledge. Among the most famous trends to appear within the city at this time was modern-day American alternative rock music. Seattle is now a celebrated destination among travelers the world over. It is one of America’s fastest growing cities in terms of its size and economy. But Seattle is also among the nation’s most diverse, as it has large demographics of people form across the globe. Few places in the United States can claim the cultural liveliness that reigns in Seattle today.

-

About the Architecture +

Renowned architectural firm George B. Post & Sons of New York created the historic designs of the Fairmont Olympic Hotel. Founded in the mid-1860s by George B. Post, the firm had made a name for itself throughout the world for its brilliant use of Beaux-Arts design principles. It was actually Post’s sons—William and James—who specifically created the Fairmont Olympic Hotel, as Post had died in 1913. Post and his children had designed a number of outstanding buildings throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, including the Equitable Life Insurance Company, the Mills Building, the Produce Exchange, the Cornelius Vanderbilt House, and the New York Stock Exchange. According to the U.S. Department of the Interior, all of Post’s designed used, “a single dominant theme adeptly handled, their elevations express internal functional and structural organization, and they represent thoughtful answers to site use and provision of light and air.” Furthermore, the organization contended that they divided, “the building into base, shaft, and crown, and employing this tripartite division as a means for giving logical organization to the exterior treatment. As such, historians today contend that the Fairmont Olympic Hotel perfectly reflects those architectural elements.

Standing 12 stories tall, the hotel itself is built around a steel frame surrounded by reinforced concrete. Laborers then filled the frame with a combination of buff-faced brick and terra cotta trim. The base of the hotel featured a wonderful blend of beautiful granite. Its original foundation formed the shape of a “U,” which wrapped around the now-demolished Metropolitan Theater. The first two floors followed this general layout, hosing the hotel’s fantastic meetings venues and public spaces. Yet, the building opened upon into an L-shape on floors three through 12, where its accommodations resided. But when the hotel’s owners commissioned the construction of another wing in 1929, the hotel metamorphosized into a “H-shaped” structure. For the hotel’s outward appearance, George B. Post & Sons used Beaux-Arts design aesthetics, specifically the Italian Renaissance-blend that was popular at the time. As with the firms previous work, the building featured the style’s iconic three-tired system of dividing a hotel’s structure. The first two floors operated as the “base,” while the third through ninth function as the “shaft.” The final three floors act as the “capital,” which displays a flat balustrade motif.

Inside, the firm embraced a variety of styles inspired by the European Renaissance, as the architecture reflected elegant contrasts complete with ornate wall carvings and beautiful decor. The hotel’s grand lobby specifically displayed the aesthetics of the English Renaissance with its use of gilt-vaulted ceilings and fine woodwork. A large elliptical staircase anchored the room that was flanked by a series of wonderful Corinthian columns. The wood trimming unique to the lobby was oak, which had been paneled from floor to ceiling. This architectural pattern appeared again within the Georgian Room, the hotel’s main dining hall. Perhaps the greatest single characteristic of the venue was its brilliant crystal chandelier. English Renaissance architecture also defined the arched mezzanine corridor that was located right above the first-floor lobby. But Spanish Renaissance design principles defined some of the other areas, such as the Fairmont Olympic Hotel’s central ballroom. George B. Post crafted the space in the style of the Spanish Renaissance, with Plateresque low reliefs defining its walls. It also contained a brilliant chandelier—similar to the Georgian Room—as well as a Mediterranean-inspired recessed balcony.

-

Famous Historic Guests +

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., historic civil rights leader of the 1960s-era Civil Rights Movement.

Joan Crawford, actress known for her roles in Mildred Place and Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?

John Wayne, actor known for his roles in The Man Who Shot Liberty Vance, True Grit, and The Longest Day.

Bing Crosby, singer and actor known for his roles in Going My Way and The Bells of St. Mary’s.

Elvis Presley, rock musician known as the “King of Rock and Roll.”

Bob Hope, comedian and patron of the United Service Organization (USO).

Charles Lindbergh, historic aviator and military officer.

Haile Selassie, Emperor of Ethiopia (1930 – 1975)

Akihito, Emperor of Japan (1989 – 2019)

Woodrow Wilson, 28th President of the United States (1913 – 1921)

Warren G. Harding, 29th President of the United States (1921 – 1923)

Calvin Coolidge, 30th President of the United States (1923 – 1929)

Herbert Hoover, 31st President of the United States (1929 – 1933)

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 32nd President of the United States (1933 – 1945)

Dwight D. Eisenhower, 34th President of the United States (1953 – 1961), and Supreme Allied Commander Europe during World War II.

John F. Kennedy, 35th President of the United States (1961 – 1963)

Lyndon B. Johnson, 36th President of the United States (1963 – 1969)

Richard Nixon, 37th President of the United States (1969 – 1974)

Gerald Ford, 38th President of the United States (1974 – 1977)

Jimmy Carter, 39th President of the United States (1977 – 1981)

Ronald Reagan, 40th President of the United States (1981 – 1989)

George H.W. Bush, 41st President of the United States (1989 – 1993)

Bill Clinton, 42nd President of the United States (1993 – 2001)

George W. Bush, 43rd President of the United States (2001 – 2009)

-

Film, TV and Media Connections +

Harry in Your Pocket (1973)

Eleanor and Franklin (1977)

House of Games (1987)

The Fabulous Baker Boys (1989)

Disclosure (1994)

Late Autumn (2010)