Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

historic hotel in new orleans

Discover the NOPSI New Orleans with convenient access to Bourbon Street. The hotel's interior fixtures have been restored to their original 1920s grandeur.

NOPSI New Orleans, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2016, dates back to 1927.

VIEW TIMELINEA contributing structure within the New Orleans Lower Central Business District, the NOPSI New Orleans has been a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2016. This fantastic hotel has offered outstanding accommodations for years, rapidly becoming one of the city’s most iconic institutions. That being said, the building that constitutes the NOPSI New Orleans has not always been a luxurious boutique hotel. On the contrary, the NOPSI New Orleans originally served as the headquarters for the city’s main power company. In fact, part of the hotel’s name—“NOPSI”—is actually an attribution to that business, the New Orleans Public Service Inc. While New Orleans Public Service Inc. itself was founded nearly a century ago, its origins harken back much further in time to the city’s first public utilities. During the 1820s, a prominent local entrepreneur named James Caldwell opened the American Theatre, illuminating it with gas-fueled chandeliers. The lighting attracted many patrons, which quickly elevated the concert hall into one of New Orleans’ best. Inspired by the popularity his gas lights had generated, Caldwell subsequently formed the New Orleans Gas Light Company to help distribute the technology throughout the community. Within a decade, Caldwell’s company had managed to provide light to several commercial neighborhoods. Other businesspeople took note, sparking the rapid creation of many additional utility companies. They subsequently developed power grids that fueled all kinds of street lamps, buildings, and even electrical street cars.

Over time, the quick spread of New Orleans’ public utility companies ironically spelled doom for the industry. The duplication of their services often resulted in inefficiency and incredibly high consumer prices. Indeed, most of the public utility companies in New Orleans would ultimately fail by 1900. After investigating the problem for several years, city officials finally established the “Settlement Ordinance” in 1922. The law would create a single master company that would consolidate all of the city’s disparate public utilities under one corporate umbrella. New Orleans Public Service Inc. was thus born, known colloquially as just “NOPSI.” It immediately set about restructuring the industry, starting with its acquisition of the New Orleans Railway and Light Company. NOSPI grew steadily, gradually emerging as the main supplier of public utilities for all of New Orleans in just a matter of years. The company had even combined all of the city’s public transit services under its purview, too! To help manage its flourishing business operations, NOPSI proceeded to establish an ornate administrative office along Baronne Street in 1927. Designed by Favrot and Livaudais, the new building stood nine stories tall and displayed some of the finest architectural finishes throughout the whole city. Perhaps the greatest feature was the ornate lobby that resembled the ground floor of a bank.

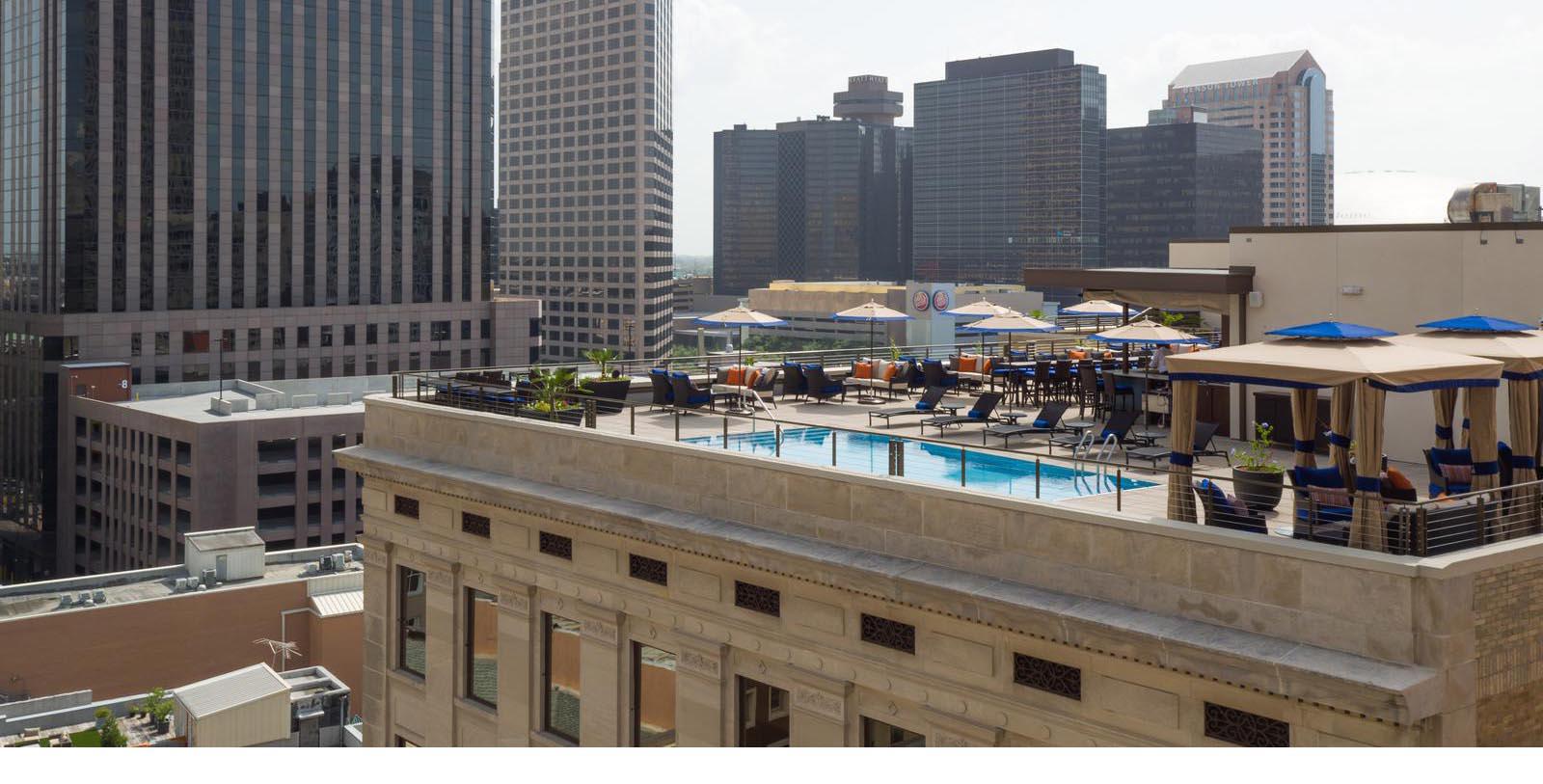

NOPSI’s executive team enjoyed the building’s eclectic so much that it remained on-site for the next several decades. But in 1983, NOPSI ended its historic occupation of the structure, choosing to relocate to a new destination on Loyola Avenue. The move was part of a much larger business transformation that saw NOPSI refocus its portfolio to exclusively provide gas and electrical services to New Orleans. Left dormant, the building’s fate remained uncertain for a while. Thankfully, salvation arrived in the form of Building and Land Technology, which sought about renovating the structure into a prominent boutique hotel. Hiring Woodward Design + Build to spearhead the project, the company set about resurrecting the historic structure back to its former glory. The construction was extensive and focused on renovating the many interior spaces into a brilliant array of upscale accommodations. Woodward Design + Build installed several spectacular facilities within the nascent hotel, too, such as the Dryades Ballroom, underCurrent, and Above the Grid. (The Dryades Ballroom itself is actually located within a neighboring structure that was integrated into the overall design.) But the work also saved the structure’s stunning historical architecture so that future generations could appreciate it. When the building reopened as the “NOPSI New Orleans” in 2017, many subsequently hailed it as an engineering masterpiece. Few locations have since rivaled the luxury and sophistication of the historic hotel in New Orleans.

-

About the Location +

NOPSI New Orleans is located just moments away from the Vieux Carré, otherwise known more popularly as the French Quarter. A National Historic Landmark, the French Quarter was first established in 1718 by French colonials under the direction of the Mississippi Company. These aspiring settlers were specifically led to the region by Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, who would go on to serve as the local colonial governor throughout much of the early 18th century. The French Crown intended for the nascent settlement to operate as an important regional port that controlled trade throughout the Mississippi Delta. After navigating the local coastline for several weeks, Bienville and his compatriots found a section of high ground above the Mississippi River that offered natural protection from flooding waters, as well as incursions against English and Spanish privateers. They named their new community “La Nouvelle-Orléans” in honor of the Duke of Orleans, a nephew of King Louis XIV.

La Nouvelle-Orléans eventually evolved into New Orleans, the capital of the French colony of Louisiana. France lost control over the city for a time during the late 18th century, when the French were forced to cede the colony to the Spanish following the Seven Years War. Yet, the Spanish gave New Orleans back to the French in 1800 at the height of the Napoleonic Wars. The town and the surrounding parishes were then part of the Louisiana Purchase, in which Emperor Napoléon Bonaparte sold 828,000 square miles of French-controlled territory in central North America to U.S. President Thomas Jefferson. The city subsequently became the capital for the new state of Louisiana in 1812, rapidly evolving into the most important port in the southern United States. This growth was offset temporarily with the outbreak of the War of 1812, with New Orleans itself becoming a battleground. It was the site of the famous Battle of New Orleans, where future president Andrew Jackson defeated the British in an incredibly lopsided victory.

New Orleans’ significance as a commercial port made it a highly valuable strategic point of interest for both the Union and Confederacy during the American Civil War. Both armies fought over the city early in the war, with the United States Navy forcing local Confederate units from the area in early 1862. It subsequently became the base for future operations by the Union in the Mississippi Delta for the duration of the conflict. Following the cessation of hostilities between the two sections in 1865, New Orleans resumed its national status as a premier port city. It even served as an integral part to the national war effort in World War II, where it became the site for the development of the crucial Higgins Boat. New Orleans has since emerged as one of the nation’s most popular tourist destinations, with millions visiting every year. The most popular attraction is the original French Quarter and its celebrated landmarks, such as Jackson Square, St. Louis Cathedral, and Bourbon Street. All of these fantastic sites wonderfully represent the original French heritage of the Vieux Carré.

-

About the Architecture +

Despite its location in New Orleans, the NOPSI New Orleans stands today as a brilliant example of Chicago Commercial-style architecture. Commonly known as “Chicago School,” this unique architectural form first emerged in America’s Windy City at the height of the Gilded Age before spreading elsewhere in America. While no actual “school” existed in Chicago that taught the aesthetic, historians today agree that a common set of design principles unified the city’s architects around the turn of the 20th century. Among the most well-known features of Chicago Commercial-style buildings involved the use of steel frames clad in masonry (usually terra cotta). The reliance upon steel and durable masonry came about following the aftermath of the Chicago Fire of 1871, when most of the city’s preexisting structures were destroyed in the calamity. But the building materials also allowed for architects to install many large plate-glass windows throughout the façade. Called the “Chicago window,” thee fixtures consisting of three-parts centered along a panel that was flanked by two smaller sash windows. The arrangement resembled a grid, in which some spaces projected out from the exterior and formed bay windows.

But the architects within the Chicago Commercial-style school of thought also believed that their buildings should reflect the prosperity and technological progress of the Industrial Revolution. As such, the structures borrowed several powerful aspects of Neoclassical architecture. Chicago Commercial-style skyscrapers were typically divided into the three distinctive sections that have historically formed what is known as the “classical column.” The lowest parts of the building acted as the base, where the most ornate architectural elements appeared. Much of the detailing occurred around the entryways, as well as any nearby windows. The middle floors of the structure often featured far less detail, which functioned as the “shaft” of the column. The grand ornamentation returned toward the final two stories, though, creating what architects called the “capital.” The “capital” was typically defined by its flat roof and brilliant cornice, as well. Many buildings across Chicago brilliantly encapsulated this architectural approach, such as the Reliance Building, the Chicago Building, and the Rookery Building. The style’s popularity rapidly appeared in other states, too, including the more business-oriented sections of New Orleans.