Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

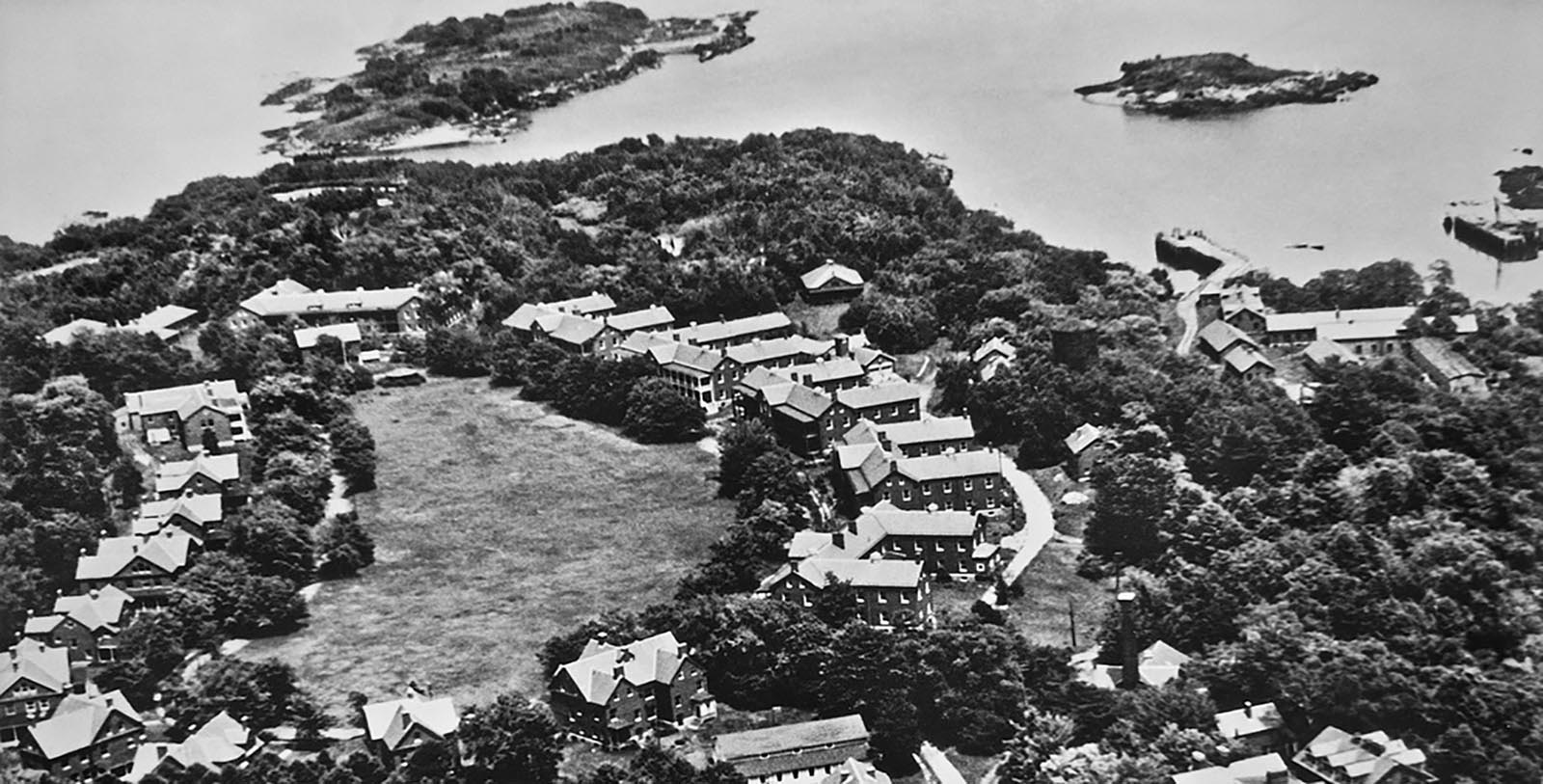

Discover The Inn at Diamond Cove, which was once a large barracks part of the greater Fort McKinley coastal defense complex.

The Inn at Diamond Cove, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2015, dates back to 1910.

VIEW TIMELINEA member of Historic Hotels of America since 2015, The Inn at Diamond Cove has been a fixture on Great Diamond Island for years. Its origins trace back to a historic military complex called “Fort McKinley” that once defended southern Maine’s coastline. In the late 19th century, Secretary of War William Crowninshield Endicott formed a joint federal organization of military and civilian officials to investigate the quality of the nation’s coastal defenses. Known informally as the “Endicott Board,” the group identified a number of locations across the United States that they believed required improved fortifications. One area that attracted their attention was Portland Harbor and its strategically important anchorage. Upon the recommendation of the Endicott Board, the federal government began constructing a sprawling fort on the northern end of nearby Great Diamond Island to protect the seaport. (Prior to this recommendation, Great Diamond Island had served as a literary retreat that had been visited by authors like Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Harriet Beecher Stowe.) Beginning in 1897, the Army Corps of Engineers spent months installing a series of powerful gun emplacements that were capable of firing several miles out to sea. But they also constructed dozens of buildings that serviced the cannons, such as storehouses, administrative offices, and living quarters for the attending soldiers. In fact, the entire complex resembled a small city when the project finally concluded in 1906.

Named “Fort McKinley” after the recently assassinated U.S. President William McKinley, the base quickly became one of the most vital military installations active along the East Coast. While then men of the U.S. Army’s Coast Artillery Corps initially occupied the base, the War Department soon decided that it needed to enlarge the garrison further. Fort McKinley thus underwent more extensive construction to accommodate the new reinforcements, which reached around 1,000 soldiers in strength. Among the buildings developed at the time were a series of barracks, including a Colonial Revival edifice known as the “Double Barrack.” Fort McKinley remained integral to the operations of the War Department for many decades thereafter, serving as the linchpin to the imposing Harbor Defenses of Portland. Indeed, the base played an integral role safeguarding Portland’s deep-water port throughout both World Wars. (The fort also temporarily lent its munitions to units serving overseas during World War I, specifically offering some of its mortars to act as pieces of railroad artillery.) However, Fort McKinley gradually became obsolete with the advent of modern aviation technology and was eventually abandoned by the Army shortly after World War II. The U.S. Navy then assumed control over the now-defunct fort, officially decommissioning it via the General Services Administration in 1961.

A variety of private landlords then owned the compound over the following years, although they failed to take great care of it. The neglect caused the buildings to fall into a state of disrepair, making their collective outlook seem bleak. Fortunately, many of the base’s structures were saved when entrepreneur Dave Bateman initiated a series of much-needed renovations during the 1990s. He transformed the entire complex into a resort community and took great pains to preserve the architectural integrity of the buildings still standing on-site. Central to Bateman’s work was the rebirth of the Double Barrack into a luxurious boutique hotel known as “The Inn at Diamond Cove,” which was finally completed in 2015. (Diamond Cove itself was a waterway that had historically divided the base into two “forks.”) The Inn at Diamond Cove has since ranked highly among Maine’s holiday retreats, offering nothing but the best in luxury and elegance. It has also continued to function as the centerpiece to Great Diamond Island’s resort community, which has entertained throngs of cultural heritage travelers interested in exploring the area’s rich history and wonderful setting. The Inn at Diamond Cove is even listed in the U.S. National Register of Historic Places as a contributing structure within the Fort McKinley Historic District.

-

About the Location +

In 1623, an English explorer named Christopher Levett received a massive land grant of some 6,000 acres near Casco Bay from King Charles I. He proposed to create a colonial settlement on a peninsula that juts out into the bay, which the local Native Americans had referred to as “Machingonne,” or “Great Neck.” Levett named the nascent community “York” after York, England, and constructed a quaint stone house along the shoreline. Sailing back to Great Britain, Levett left a company of ten men in his wake to monitor the budding colony. But the settlement failed, and Levett’s men abandoned the house. Nevertheless, the English returned nearly a decade later when George Cleeve and Richard Tucker established a fishing village called “Casco.” It remained isolated for the next 25 years until the neighboring Massachusetts Bay Colony annexed the whole territory in 1658. Renamed as “Falmouth,” the town continued to exist in relative harmony for some time. Then in 1676, the Abenaki people sacked the settlement amid a conflict called “King Phillip’s War.” (The war was a brief, yet intense struggle between English colonists and New England’s indigenous people for ultimate control over the region.) Barely given time to recover, France then attacked Falmouth at the Battle of Fort Loyal during the Nine Years’ War. The French colonists and their allies had targeted a citadel named “Fort Loyal,” which the English had constructed as a deterrent against potential raiders following King Phillip’s War. The French then destroyed the community, before heading toward the frontier of nearby New Hampshire Colony.

Falmouth was assaulted a final time during the American Revolutionary War. Having largely rebuilt from its earlier tribulations, the community had become a vibrant seaport and commercial center. The British Royal Navy recognized the town’s economic importance and subsequently destroyed it during the “Burning of Falmouth.” Undeterred, the residents once again resurrected the settlement, choosing to reorient its downtown core at the site of today’s Old Port district. The economy came roaring back and more people immigrated to the city. Its size had grown so great that Falmouth’s residents were able to form a new community out of the area’s southern neighborhoods in 1786. Called “Portland,” it encompassed much of the original colonial settlement that had formed around Casco Bay. Portland soon became the capital of Maine following its admission into the union in 1820 and maintained that title until the early 1830s. The arrival of the Grand Trunk Railway in the mid-1850s further augmented its status as a vibrant center for trade, as Portland’s merchants started shipping an unprecedented amount of goods from Canada. Industrialization even began to alter Portland’s landscape, with most of the construction occurring after the American Civil War. Perhaps the greatest industrial enterprise to operate within the community at the time was the Portland Company, which manufactured all kinds of vehicles, ranging from steam locomotives to fire engines.

As the 20th century dawned, Portland emerged as one of the most prosperous cities in all of New England. Heavy industry had surpassed its traditional maritime trade, although it never entirely replaced it. Nevertheless, shipbuilding remained an important part of the local economy, especially during both World Wars. World War II particularly had a profound impact on Portland, as the U.S. Navy opened many military installations across the city. Almost as soon as the war began in 1939, the Navy turned Casco Bay into a fortified base that serviced merchant convoys slated to cross the ocean. Those naval vessels—some as large as battleships—were specifically tasked with hunting down U-boats once America finally entered the conflict two years later. Many auxiliary offices for the U.S. Navy appeared in Portland, such as a Fleet Post Office, a Naval Dispensary, and a Navy Relief Society office. Sailors learned a wide range of skills in the city, too, such as long-range navigation (LORAN), fire-control radar operations, gunnery spotting, and anti-submarine warfare. Portland has since remained one of the most vibrant communities in the region, with its hallmark maritime commerce playing a significant role in its continued vitality. Tourism is also a significant part of its current identity, as people from the world over travel to Portland every year to experience its unique heritage. Few places in New England are better for a wonderful cultural experience than Portland, Maine.

-

About the Architecture +

The Inn at Diamond Cove stands today as a wonderful modern interpretation of Federal-style architecture. Historically speaking, Federal architecture dominated American cities and towns during the nation’s formative years, which historians best identify as lasting from 1780 to 1840. The name itself is a tribute to that period, in which America’s first political leaders sought to establish the foundations of the current federal government. Fundamentally, the architectural form had evolved from the earlier Georgian design principles that had greatly influenced both British and American culture throughout most of the 18th century. The similarities between the two art forms have even inspired some scholars to refer to Federalist architecture as a mere refinement of the earlier Georgian aesthetic. Oddly enough, the architect deemed responsible for popularizing Federal style in the United States, was in fact, not an American. Robert Adams was the United Kingdom’s most popular architect at the time, and his work largely infused Neoclassical design principles with Georgian architecture. (This is also the reason why some refer to Federal architecture as “Adam-style architecture.”) As such, his new variation spread quickly across England, defining its civic landscape for much of the Napoleonic Era. Despite the bitter resentments that many Americans harbored toward Great Britain after the American Revolutionary War, their cultural perceptions of the world were still largely influenced by the country. Adams’ new take on Georgian design principles thus rapidly spread across the United States, becoming the inspiration for its Federal-style architecture!