Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

Discover the Mission Inn Hotel & Spa, which has been a luxury cornerstone of beautiful Riverside since 1876.

The Mission Inn Hotel & Spa, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 1996, dates back to 1876.

VIEW TIMELINE

Mission Inn Hotel and Spa

The Mission Inn Hotel & Spa has remained faithful to the grand style and ambiance enjoyed by its first guests. Today’s Mission Inn continues the original splendor initiated by founder Frank Miller, thanks to the genuinely caring attention of Duane and Kelly Roberts.

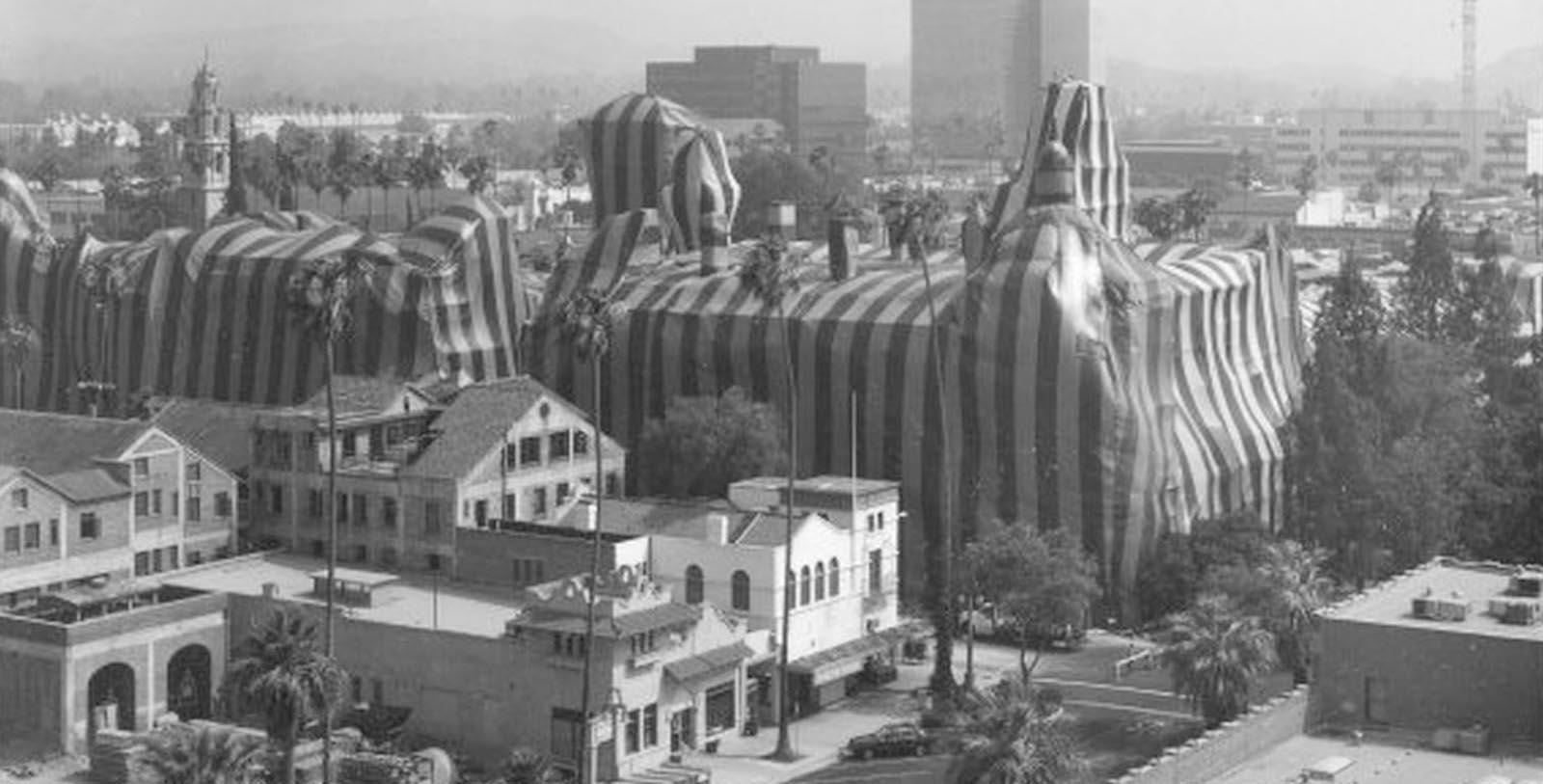

WATCH NOWA member of Historic Hotels of America since 1996, The Mission Inn Hotel & Spa is a cherished local landmark in downtown Riverside. Despite its grand appearance, the hotel originally opened as a simple boarding house called “Glenwood Cottage.” Established in 1875, Glenwood Cottage was actually a source of secondary income for civil engineer Christopher Columbus Miller and his family. (Miller himself had arrived in Riverside to help create the city’s nascent public water system a year prior.) Surprisingly, Glenwood Cottage proved to be an incredibly popular destination among those passing through the area. Upon realizing its potential, C.C. Miller’s son, Frank Augustus, purchased the business for a sum of $5,000 in 1880. He immediately set about enlarging and improving the building with the intent of transforming it into one of California’s preeminent vacation getaways. Miller subsequently partnered with railroad tycoon Henry E. Huntington, and together, the two hired architect Arthur Benton to reconfigure Glenwood Cottage’s entire layout. Benton worked with Huntington and Miller to create a brilliant design that embraced a number of architectural styles, specifically Spanish Colonial Revival-style architecture. Taking nearly two decades to complete, the Mission Wing of the building debuted in 1903. Miller then launched the business as the “Glenwood Mission Inn” before renaming it simply as the “Mission Inn.” He did not rest after the addition opened, as he spent the next 30 years continuously renovating the structure. Three additional wings appeared within that span of time, known as the “Cloister Wing,” the “Spanish Wing” and the “Rotunda Wing.” However, the building also contained a new series of castle-like towers, Mediterranean domes, flying buttresses, and sprawling arcades. Miller even filled his stunning hotel with rare antiquities that he had acquired from his travels through Europe and Asia.

By 1931, Miller’s magnificent destination had grown so large that it spanned a whole city block. But the eccentric Miller died some four years later, leaving the business to the care of his daughter, Allis Hutchings. Hutchings in turn supervised the Mission Inn for the next two decades right up until her own passing in 1956. Nevertheless, the hotel had already fallen into a state of decay, which grew worse after Hutchings’ death. Her family members subsequently decided to sell the Mission Inn to a hotelier from San Francisco named Benjamin Swig. In a desperate attempt to revitalize the business, Swig sold off most of Frank Augustus Miller’s antique collection and recast parts of the exterior in Mid-century Modern aesthetics. His plan failed though, and the Mission Inn entered a prolonged period of fluid ownership and financial instability. Then in 1969, a group of concerned citizens eventually organized to save the hotel out of a justifiable fear that it would be destroyed by real estate developers. They formed an organization called “Friends of the Mission Inn” to promote the hotel’s history and its remaining historical collection of artifacts. Nevertheless, the hotel continued to struggle, prompting the City of Riverside to outright purchase the Mission Inn for preservation purposes. It created a non-profit entity called the “Mission Inn Foundation” to manage the building in partnership with the city’s interests. The Mission Inn Foundation and the Friends of the Mission Inn also worked closely in unison to get the building successfully designated as a National Historic Landmark. But true salvation finally arrived during the early 1990s, when local Riverside entrepreneurs Duane and Kelly Roberts acquired the ailing Mission Inn. They quickly set about restoring the structure back to its former glory, rebranding the building as “The Mission Inn Hotel & Spa.” The Roberts family also collaborated closely with the Friends of the Mission Inn and the Mission Inn Foundation to ensure that the history of the building was properly conserved for future generations to appreciate. All three groups continue to work together today to ensure that the building’s wonderful character will endure for years to come.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the hotel’s storied past involves the sheer number of celebrity guests who have graced its halls. Almost as soon as Miller took control of the business, luminaries from around the world vied to reserve one of its guestrooms. Among the first illustrious patrons to arrive were great Gilded Age icons like vaudeville star Lillian Russell, French stage actress Sarah Bernhardt, and renowned illusionist Harry Houdini. Over the years, that venerable list grew to include some of the biggest entertainers in the film industry. Many of Hollywood’s elite traveled to The Mission Inn Hotel & Spa, such as Judy Garland, Bette Davis, Ginger Rogers, Mary Pickford, Cary Grant, Spencer Tracy, and Bob Hope. Some, including Clark Gable, stayed while shooting various films nearby. In fact, eight different movies were filmed either around or inside the hotel, starting with The Vampire in 1918. (Other films include Idiot’s Delight, Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here, and Buddy Buddy.) The Mission Inn Hotel & Spa has allured more than famous movie stars, having also entertained numerous leading intellectuals and social activists, like Booker T. Washington, Susan B. Anthony, and Albert Einstein. Many prominent American industrialists even stayed at the hotel, including the John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, and Henry Ford. The single greatest kind of guest to visit The Mission Inn Hotel & Spa have been U.S. Presidents, starting with Benjamin Harrison in 1891. (Around a dozen U.S. Presidents have since visited the building, like Theodore Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy, and George W. Bush.) A few of those esteemed guests had arrived before they became President, too, such as Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan. Nixon specifically married his wife Pat inside the hotel in what is now known as the “Presidential Lounge,” while Reagan honeymooned on-site with his wife, Nancy, during the early 1950s!

-

About the Location +

Long before present-day Riverside existed, the area was inhabited by Native American tribes of the Cahuilla and Serrano people. Over time, powerful Mexican landowners moved into the region and settled the land through various grants. Known as “Californios,” the new migrants developed massive ranches that extended for thousands of acres. As such, those individuals were often very influential figures in both the local economy and politics. But in the 1860s, one Californio sold his estate—Rancho Jurupa—to Louis Provost, who wished to develop the area as a massive sericulture farm. (Sericulture is the cultivation of silkworms to produce silk.) Unfortunately, the climate proved to be inconducive for such an enterprise, and Provost’s experiment went bankrupt. In the wake of the farm’s failure, a nationally renowned politician named John W. North acquired the site. He hoped to create a “colony” dedicated to promoting communal education and artistic endeavors. Through his “Southern California Colony Association,” North actively began recruiting people from across the world to settle his new community in early 1870. Most of the area’s earliest residents hailed from the eastern United States, although a sizeable group of expats from Canada and England arrived, too. The town gradually expanded over the next several years, as a variety of businesses opened downtown. Riverside’s new residents even founded the first ever golf course and polos grounds in all of Southern California! By 1883, the community had grown large enough that the state government formally incorporated it as a city.

The future of Riverside changed forever though, when Eliza Tibbets planted three Brazilian orange trees on her land. Sent by her friend William Saunders of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the trees themselves were only supposed to be a simple fixture in her garden. But when a rampaging cow trampled one of the trees, Tibbets decided to move the surviving two to the home of Sam McCoy for safe keeping. McCoy and Tibbets then chose to move the two trees again, with one placed in downtown Riverside and the other planted at The Mission Inn Hotel & Spa. (Interestingly, U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt—a noted conservationist—personally planted the second tree during his time at the hotel in 1903.) Both plants subsequently thrived in the city’s climate, inspiring many others to nurture their own orange trees. A thriving citrus industry quickly emerged in just a matter of years, with more than 250,000 orange trees planted inside the city limits. As the citrus farms took off at a rapid pace, so did the nascent hospitality sector that persisted for decades. Aspiring hoteliers constructed a few hotels and inns in turn, driven by the large influx of travelers heading out into the surrounding countryside. The greatest building to operate was Frank Augustus Miller’s Mission Inn, which had undergone a gradual series of massive renovations since the 1880s. Today, Riverside is among the most luxurious destinations in Southern California. Its most appealing cultural attraction continues to be its historic citrus industry, epitomized by such historic landmarks as the Parent Navel Orange Tree and the California Citrus State Historic Park.

-

About the Architecture +

Standing six floors in height, the building resembles one of the Spanish missions that proliferated throughout California centuries ago. Frank Augustus Miller constructed his beautiful hotel through a series of phases that spanned the better part of six decades. Specifically designed by architect Arthur Benton, the first major addition debuted as the “Mission Wing” in 1903. Three additional wings subsequently followed suit, with the last one completed shortly before Miller’s death during the 1930s. Those sections were known as the “Cloister Wing,” the “Spanish Wing” and the “Rotunda Wing,” respectively. But the building also contained a wealth of special spaces that clearly distinguished it from its various competitors. For instance, the ornate central lobby led to a brilliant space called the “Presidential Suite,” which featured elaborate wood paneling that Miller imported directly from a Belgian convent. Two more venues connected to the lobby, as well—The Closter Music Room and the Refectorio. The Cloister Music Room resembled a beautiful baronial hall that one would find inside a historic Spanish castle. Meanwhile, the Refectorio contained a groined-arched stone ceiling and a wealth of stained-glass windows. A 300-foot-long corridor extended from the front of the hotel, too, which led guests toward such memorable areas as the Carmel Room and its gorgeous, frescoed walls. The Spanish Art Gallery was also located along the hallway, which housed most of Frank Augustus Miller’s fine collection of rare antiques. Furthermore, according to the U.S. National Park Service:

- “On the third floor is the Paseo de Las Palmas, an open porch around the upper story of the Mission Wings, and the Paseo de los Moros…Still higher is the Alhambra Court, the Authors' Terrace, the Sunset Roof Garden with its flowered covered walk, the Carillon Tower, and Star Court. On other intermediate levels are Musicians' Balcony, Spanish Terrace, and various additional open corridors.”

A stunning patio sat at the center of the building that was anchored by a wonderful fountain. Miller installed an 18th-century Bavarian clock above the area, which he supported by a series of ostentatious columns. He also commissioned the construction of a quaint structure known as the “St. Francis Chapel.” Its most striking feature was four large, stained-glass windows, as well as two original mosaics created by Louis C. Tiffany in 1906. Salvaged from the Madison Square Presbyterian Church in New York City, the chapel’s main purpose was to house those pieces of art. Miller also installed a beautiful Baroque-inspired “Rayas Altar,” which Mexican craftsmen created with cedar wood and gold leaf coverings back during the 18th century. The “Garden of Bells” resided inside the chapel that hosted a collection of over 800 historic bells, including one that dated back to the 13th century. Additional artifacts displayed within the space were the 19th-century Nanjing Bell, a massive Japanese statue called the “Amitahba Buddha,” and a series of priceless paintings by Henry Chapman Ford and William Keith. Among the last areas to debut inside the hotel during Frank Augustus Miller’s lifetime was the St. Francis Atrio. Inside, Miller’s son-in-law, DeWitt Hutchings, eventually created the “Famous Fliers’ Wall,” which paid homage to notable aviators. Today, more than 150 pilots are remembered at the St. Francis Atrio with their names inscribed on a series of copper wings attached to the wall.

When Frank Augustus Miller first designed The Mission Inn Hotel & Spa with Arthur Benton, he relied upon a variety of architectural styles to create its visionary layout. But many historians today consider the most prominent type of architecture to appear throughout the facility to be Spanish Colonial Revival-style. Also known as “Spanish Eclectic,” this architectural form is a representation of themes typically seen in early Spanish colonial settlements. Original Spanish colonial architecture borrowed its design principles from Moorish, Renaissance, and Byzantine forms, which made it incredibly decorative and ornate. The general layout of those structures called for a central courtyard, as well as thick stucco walls that could endure Latin America’s diverse climate. Among the most recognizable features within those colonial buildings involved heavy carved doors, spiraled columns, and gabled red-tile roofs. Architect Bertram Goodhue was the first to widely popularize Spanish Colonial architecture in the United States, spawning a movement to incorporate the style more broadly in American culture at the beginning of the 20th century. Goodhue received a platform for his designs at the Panama-California Exposition of 1915, in which Spanish Colonial architecture was exposed to a national audience for the first time. His push to preserve the form led to a revivalist movement that saw widespread use of Spanish Colonial architecture throughout the country, specifically in California and Florida. Spanish Colonial Revival-style architecture reached its zenith height the early 1930s though, although a few American businesspeople continued to embrace the form well into the late 20th century.

-

Famous Historic Guests +

Albert Einstein, Nobel Prize winning physicist known for his role in developing quantum theory.

Amelia Earhart, pioneering aviator who was the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean.

Andrew Carnegie, founder of the U.S. Steel Corporation.

Bette Davis, actress known for her roles in All About Eve, Jezebel, and What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?

Bob Hope, comedian and patron of the United Service Organization (USO).

Booker T. Washington, educator and former slave who eventually founded Tuskegee University.

Carrie Jacobs-Bond, signer who wrote 175 pieces of popular music, including her famous “A Perfect Day.”

Cary Grant, actor known for such roles in To Catch a Thief, Charade, and North by Northwest.

Charles Boyer, actor known for his roles in The Garden of Allah, Algiers, and Love Affair.

Clark Gable, actor known for his roles in It Happened One Night, Mutiny on the Bounty, Gone with the Wind.

Eddie Cantor, singer known for such songs like “Makin’ Whoopie,” “If You Knew Susie,” and “Merrily We Roll Along.”

Ethel Barrymore, actress regarded by many to be “The First Lady of American Theatre.”

Fess Parker, actor best remembered for his portrayal of Davy Crockett in the television series, Davy Crockett.

Ginger Rogers, actress and dancer remembered for her roles in such films like Kitty Foyle, Top Hat, and Swing Time.

Glen Campbell, musician known for such singles like “Galveston,” “Rhinestone Cowboy,” and “Wichita Lineman.”

Harry Chandler, newspaper publisher who became one of the biggest real estate developers in early 20th century.

Harry Houdini, famous illusionist and stunt performer.

Helen Keller, social activist and first deaf-blind person in American history to successfully earn a college degree.

Henry Ford, founder of the Ford Motor Company and inventor of the historic Model-T.

Henry E. Huntington, railroad magnate and owner of the Pacific Electric Railway.

Hubert H. Bancroft, author and ethnologist who wrote several well-known books about the western United States.

Jack Benny, comedian known for The Jack Benny Program.

John D. Rockefeller, founder of the Standard Oil Company.

John Muir, conservationist regarded today as the “Father of the National Parks.”

Joseph Pulitzer, newspaper publisher who produced the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and the New York World.

Judy Garland, actress and singer known for her roles in A Star is Born, Meet Me in St. Louis, and Wizard of Oz.

Lillian Russell, actress and singer known for her performances at the Weber and Fields’ Music Hall.

Mary Pickford, actress known for her role in the silent film Coquette.

Merle Haggard, musician known for such singles like “Mama Tried,” “Poncho and Lefty,” and “Workin’ Man Blues.”

Sarah Bernhardt, stage actress known for her roles in such plays like La Tosca, Ruy Blas, and La Dame Aux Cameilas.

Spencer Tracy, actor known for such role sin Adam’s Rib, Woman of the Year, and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner.

Susan B. Anthony, civil rights activist and abolitionist involved with the National American Woman Suffrage Association.

W.C. Fields, comedian known such films like The Bank Dick, It’s a Gift, and Never Give a Sucker an Even Break.

William Randolph Hearst, publisher of the New York Journal and founded Hearst Communications.

Gustavus Adolphus VI, King of Sweden (1950 – 1973)

Prince Kaya Kuninori, member of the Japanese Imperial family from the Meiji Period.

Pat Nixon, First Lady to former U.S. President Richard Nixon

Nancy Reagan, First Lady to former U.S. President Ronald Reagan

Benjamin Harrison, 23rd President of the United States (1889 – 1893)

William McKinley, 25th President of the United States (1897 – 1901)

Theodore Roosevelt, 26th President of the United States (1901 – 1909)

William Howard Taft, 27th President of the United States (1909 – 1913) and 10th Chief Justice of the United States (1921 – 1930)

Herbert Hoover, 31st President of the United States (1929 – 1933)

John F. Kennedy, 35th President of the United States (1961 – 1963)

Richard Nixon, 37th President of the United States (1969 – 1974)

Gerald Ford, 38th President of the United States (1974 – 1977)

Ronald Reagan, 40th President of the United States (1981 – 1989)

George W. Bush, 43rd President of the United States (2001 – 2009)

-

Film, TV and Media Connections +

The Vampire (1918)

Idiot’s Delight (1938)

Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here (1969)

The Magician: Man on Fire (1973)

The Wild Party (1975)

Black Samurai (1977)

Buddy Buddy (1981)

Vibes (1988)

Sliders: The Exodus, Part I (1997)

Sliders: The Exodus, Part 2 (1997)

The Man in the Iron Mask (1998)

-

Women in History +

Amelia Earhart: A regular guest at The Mission Inn Hotel & Spa, Amelia Earhart was a legendary aviator who bore the distinction of being the first female to pilot a plane across the Atlantic Ocean. Climbing aboard a Fokker Trimotor dubbed “Friendship,” Earhart and her copilot, Wilmer Stultz, began the historic trip from an airfield in Newfoundland in June of 1928. In just under a single day, Earhart and Stultz landed at Pwll in South Wales. She became an overnight international celebrity for the achievement, encountering a massive ticker-tape parade in New York City upon her return to the United States. President Calvin Coolidge even held a reception in her honor at the White House shortly thereafter, too. Earhart then followed up her grand achievement five years later, when she completed a transatlantic solo flight from Canada to Northern Ireland. Becoming the first woman to finish such a trip alone, Congress bestowed Earhart with the Distinguished Flying Cross. Her fame only continued to grow, as tales of her accomplishments captivated countless Americans. In fact, Earhart’s celebrity status caused her to develop a close friendship with Eleanor Roosevelt during the mid-1930s. But when she was not busy flying, Earhart served as visiting faculty member in aeronautical engineering at Purdue University, and vigorously supported the causes championed by the National Women’s Party. Earhart also founded the Ninety-Nines, an all-female international organization that supported the professional growth of female pilots. Nevertheless, her career was tragically cut short in 1937, when she disappeared while attempting a circumnavigational trek across the globe.

Susan B. Anthony: Another distinguished guest to stay at The Mission Inn Hotel & Spa was the celebrated civil rights activist Susan B. Anthony. Born into a Quaker family in Massachusetts, Anthony had been raised to believe in the universal equality of all people. After moving around the Northeast to obtain an education, she took teaching in upstate New York. Then during the 1840s, Anthony decided to move back to her family, who had recently relocated to Rochester. There she met with many prominent civil rights activists involved in the antebellum abolition movement, including Frederick Douglass, Wendell Phillips, and William Lloyd Garrison. Upon hearing them preach about the evils of slavery, she became committed to ending the institution across the United States. She subsequently gave dozens of speeches that attacked the practice of human bondage, eventually serving as the chief agents of the American Anti-Slavery Society. Around the same time, Anthony attended the very first Women’s Rights Convention in neighboring Seneca Falls and immediately joined the fight for female suffrage. Coordinating with the great Elizabeth Cady Stanton, she began running a second oratory circuit that championed the enfranchisement of all the women in the nation. She even became a fierce advocate for the national temperance movement, forming the Women’s New York State Temperance Society alongside Stanton in 1852.

Once the American Civil War formally eradicated slavery from the United States, Anthony committed herself completely to the causes of women’s suffrage. In fact, Anthony initially opposed the 14th and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, because they did not guarantee voting rights to all women. She helped form the National Women’s Suffrage Association in the late 1860s as a means of pushing for a separate constitutional amendment that would grant universal female enfranchisement. Anthony also started publishing a new radical periodical called, The Revolution, and even hosted a massive gathering of suffragettes in Washington, D.C. She continued to lecture as well, earning the ire of national newspapers across the country. In a daring move during the 1872 presidential election, she was even arrested after attempting to cast a vote. Anthony nonetheless traveled from state to state in a tireless campaign to advocate for women’s suffrage, often alongside her lifelong friend, Elizabeth Cady Stanton. After Stanton stepped down as the leader of the National American Woman Suffrage Organization in 1890, Anthony took over with Carrie Chapman Catt acting as her direct lieutenant. By this point, Anthony had become something of a national icon. Unfortunately, her age had caught up to her and she retired from the National American Woman Suffrage Organization in 1900. To the sadness of many, she passed away six years later. But the 19th Amendment passed in 1920 thanks in large part to her constant activism, which finally the right to vote to all women.