Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

Discover Battle House Renaissance Mobile Hotel & Spa, which sits on Andrew Jackson’s military headquarters during the War of 1812.

Battle House Renaissance Mobile Hotel & Spa, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2009, dates back to 1852.

VIEW TIMELINEA member of Historic Hotels of America since 2009, the history of this magnificent historic hotel dates back to the start of the 19th century. The present site of the Battle House Renaissance Mobile Hotel & Spa once housed the headquarters of General—and future U.S. President—Andrew Jackson during the War of 1812. In the wake of the conflict, local businesspeople ran a couple hotels at the location. The first business to debut was the “Franklin House” in 1825, which hotelier Daniel White had moved from Cahaba entirely on floats. Yet, a series of destructive floods ruined the building and forced White to close permanently. But in 1829, other hoteliers restored the structure and opened it as the “Waverly Hotel.” It, too, met a grizzly fate, as a fire completely burnt it to the ground three decades later. Then, in 1852, James Battle and his two brothers—John and Samuel—decided to purchase the lot to construct their own hotel. They hired noted architect Isaiah Rogers to spearhead the project, who subsequently designed the new building with Greek Revival-style architecture. Called the “Battle House Hotel,” it stood a stunning four stories in height, and featured a two-level gallery of cast iron. Thankfully, their business encountered good fortune over the coming years. Many illustrious guests soon visited the Battle House Hotel, including the likes of Senator Henry Clay, General Winfield Scott, and U.S. President Millard Fillmore. Senator and presidential candidate Stephan A. Douglas even stayed inside the building on the night of Election Day in 1860. (Douglas would lose the four-way contest to Abraham Lincoln, who many now regard as one of the best presidents in American history.)

The Battle House Hotel remained a fixture in Mobile well into the 20th century, until an industrial accident greatly compromised the building in 1905. Undaunted, D.R. Burgess and several other local merchants raised $1.35 million to rebuild the Battle House Hotel. They hired the renowned New York-based architect Frank M. Andrews to redesign the whole structure out of fireproof steel and concrete. Construction began in earnest in 1906 and lasted for some three years. When the building finally opened once again, it stood as a wonderful example of Georgian Revival-style architecture. It also stood an additional three stories in height and sat upon a brilliant “U-shaped” foundation. Soon enough, throngs of affluent guests descended upon the business to reserve one of its many ornate guestrooms. Perhaps the greatest visitor to grace the hotel with their presence at the time was President Woodrow Wilson, who traveled to the building shortly after his inauguration in 1913. Upon his arrival, members of the Southern Commercial Congress held a “Presidential Breakfast” in his honor that was attended by nearly 200 guests. Hotel staff at the time recalled how seemingly countless Secret Service agents had sprawled across the building’s interior. Afterward, he traveled to the neighboring Lyric Theatre, where he gave a speech repudiating the Monroe Doctrine as a means of appeasing the country’s Latin American allies. In fact, it was here that President Wilson gave his now-famous remark: “The United States will never again seek one added foot of territory by conquest.”

Having operated as an independent hotel for more than a century, the proprietors of the Battle House Hotel sold it to Sheraton Hotels and Resorts in 1958. It subsequently remained with the company for some time, operating under the name of the “Sheraton-Battle House.” Gotham Hotels then acquired the Sheraton-Battle House from Sheraton Hotels, buying the building alongside 17 other historic structures. It renamed the business back to the “Battle House Hotel,” and attempted to restore its earlier architectural features. Yet, the company eventually tired of the hotel and sold it to a group of local citizens in 1968, who rebranded it as the “Battle House Royale.” But the new ownership group failed to make the Battle House Royale profitable, and it quickly faced a series of daunting financial challenges. Despite several remedies to fix the ailing business, the hotel closed to an uncertain future in 1974. Fortunately a year later, the U.S. Department of the Interior listed the empty hotel on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places, thus protecting it from any potential demolition plans. True salvation for the ailing historic hotel finally arrived when Retirement Systems of Alabama began restoring it alongside Smith Dalia Architects in 2003. The company had revitalized the building while they developed the “RSA Battle House Tower” next door, which featured additional hotel accommodations. The work took four years to finish and reinvigorated the hotel’s great historical character. Today, this wonderful historic holiday destination is part of Marriott International’s prestigious Renaissance Hotels brand and operates as the “Battle House Renaissance Mobile Hotel & Spa.” Travelers from across the nation still rave about its unmatched hospitality and luxurious amenities.

-

About the Location +

The city of Mobile is one of the most historic places in the nation. The site of the present city was originally explored by the Spanish as early as the beginning of the 16th century, shortly after Christopher Columbus established the first European colony in the “New World.” Yet, the first permanent European settlers arrived nearly two centuries later, when Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville led a group of French colonists several miles up the Mobile River in 1702. Here, he established “Fort Louis de la Louisiane” on behalf of the Colonial Governor of French Louisiana—who happened to also be his brother—Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville. As disease began ravaging the population, Bienville instructed the colonists to relocate downstream to the river’s confluence with Mobile Bay. They erected a new fort in 1711 and small community quickly emerged over the next several decades. The small village soon became known as “Mobile,” named for the “Maubilla” Indians that once lived nearby. Even though the colonial outpost struggled to grow in size, its functioned as the capital of Colonial Louisiana during the first years of its existence. But when war erupted between France and Spain in 1719, Bienville decided to relocate the colony’s administrative offices further west to the emerging settlement of Biloxi. Meanwhile, Mobile effectively served as a military outpost between the two warring kingdoms, with the local colonial populations fighting against each other. Mobile eventually found its footing within the French Empire, acting as a major commercial trading center with the local Native Americans. The British eventually seized the entirety of Mobile Bay, though, after the Seven Years’ War, when France ceded it to Great Britain. The area subsequently joined the British colony of “West Florida,” until it was given to the Spanish following the American Revolution.

Mobile and the rest of the modern Alabama coastline continued to be a part of Spanish-controlled Florida until the War of 1812. An American army stationed in New Orleans invaded the region under the pretense that its merchants were selling arms to native tribes allied with the British. But the United States had long disagreed over the exact location of Spanish Florida’s western border, which further incentivized the Americans to seize the region. Spain ultimately relented, signing the territory over to the United States. Mobile and the land surrounding Mobile Bay joined the Mississippi Territory, although that union proved to short-lived. The territory subsequently split in two, with the western half becoming the state of Mississippi in 1817. The eastern portion bordering Georgia joined the nation as “Alabama” two years later. While the state capital was founded in Montgomery to the north, Mobile emerged as Alabama’s most prosperous city. It rapidly became one of the busiest port cities in the South, second only to New Orleans in its affluence. In fact, by the 1850s, Mobile was one of the top five seaports in the whole nation. Its commercial importance eventually played a major role during the American Civil War of the mid-19th century, when the newly formed Confederacy relied upon its maritime commerce to supply its nascent war effort. The Union eventually attempted to blockade the city, but ships known as blockade runners occasionally managed to evade capture. Mobile’s significance to the rebel war effort became all the more vital when New Orleans was occupied by northern soldiers in early 1862. Eventually, the Lincoln administration sought fit to seize Mobile itself, instructing Admiral David Farragut to attack the city. While the city itself never fell to the North, its surrounding harbor was effectively captured by Farragut’s command following the Battle of Mobile Bay in 1864.

After the war, Mobile struggled to reassert itself as one of America’s preeminent ports, eventually going bankrupt in 1879. But its economy gradually improved, especially after local ship captains began importing tropical fruits alongside their normal exports of lumber and cotton. The maritime trade received a much-needed boast, though, in 1914, when construction finally ended on the Panama Canal, allowing the city’s merchants to trade more easily with markets on the other side of the world. Later developments emerged, too, that helped the city’s naval commerce to return, including the creation of the Intracoastal Waterway, as well as the Alabama State Docks. Industrialization also took root in the city around the same time, giving rise to factories that contributed greatly to the development of a localized shipbuilding industry. Perhaps the most prominent shipbuilding company to appear in Mobile was the Alabama Drydock and Shipbuilding Company, which constructed countless cargo vessels during World War II. Another prominent company was a subsidiary of the Gulf Shipbuilding Corporation called the Waterman Steamship Corporation. It subsequently built freighters, destroyers, and minesweepers in the war, too. Other major industries appeared by the middle of the century, including chemicals, textiles, and vehicle components. Paper products also became a central fixture in the city’s economy, with the Scott Paper Company and International Paper employing a large segment of its population. But the time period also saw the emergence of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, in which racial equality became a major aspect of the city’s political landscape. While Mobile had been more open to desegregation than most other southern cities, its education system remained separated on the basis of race well after the U.S. Supreme Court had ruled the practice unjust. In 1963, three African American students sued the Mobile County School Board in federal court, citing the majority decisions presented in Brown v. Board of Education. The federal court ruled in their favor, forcing Murphy High School to completely desegregate by the next school year.

Today, Mobile is a vibrant, modern city filled with all sorts of outstanding cultural attractions to visit. Among the most popular destinations in the area are GulfQuest National Maritime Museum, Gulf Coast Exploreum Science Center, and a colonial citadel named “Fort Conde.” Its shoreline is also home to Battleship Memorial Park, where the famed World War II-era battleship, the USS Alabama, acts as a museum. Modern Mobile is also home to one of the earliest authentic Mardi Gras festivals in the whole United States, rivaling New Orleans in its grandiose character. Its downtown still reflects much of its historic character, as evidenced by the Victorian-era mansions and cottages that line its historic Oakley Garden District. To the west, even more historic buildings reside within the fabulous Old Dauphin Way District. Few places are truly better in the Gulf Coast for a historically inspired vacation than the brilliant city of Mobile.

-

About the Architecture +

Mobile native D.R. Burgess and several other local merchants decided to rebuild the historic Battle House Hotel after the previous iteration suffered a structural accident in 1905. It ultimately cost the group $1.35 million three years to redevelop. They had hired renowned architect Frank M. Andrews to spearhead the project, who was reputed throughout the country for his work in New York City. Andrews subsequently designed a stunning seven-story structure made completely of fireproof steel and brick. The street-level exterior featured a projecting portico that contained several ornate Tuscan columns. Furthermore, recessed Tuscan loggias with individual window balustrades resided above the portico itself. A wide, entablature surmounted by cast iron balconies existed on the third story, while every other floor had lavishly articulated keystones. The upper sections of the building had a cast iron balcony, too, which extended for two whole stories. Inside, the lobby served as the central component to the building’s entire “U-shaped” floorplan. Some of its most noteworthy characteristics included a domed skylight, elaborate plasterwork, and walls painted in the style of trompe-l'œil. The dome itself was over 42 feet tall and 63 feet wide, and had fleur-de-lis designs placed on every glass panel. Several gorgeous venues were located right off of the lobby as well, such as the Trellis Room and the Crystal Ballroom. Built with a barrel vaulted ceiling, the Trellis Room had stunning architectural elements, such as a “Tiffany glass” skylight. The Crystal Ballroom, on the other hand, featured beautiful detailing that displayed an agricultural theme. Andrews had made such a decision, because the Battle House Hotel was still popular among the area’s wealthy planters. Many of those individuals had often attended extravagant balls at the Battle House Hotel. The most popular celebrations in the space continued to be grand galas held on New Year’s Eve and Mardi Gras, as well as weddings and business meetings.

The Battle House Hotel displays a brilliant blend of Colonial Revival-style architecture, specifically a subset known as “Georgian Revival.” Colonial Revival and its various offshoots today is perhaps the most widely used building form in the entire United States. It reached its zenith at the height of the Gilded Age, where countless Americans turned to the aesthetic to celebrate what they feared was America’s disappearing past. The movement came about in the aftermath of the Centennial International Exhibition of 1876, in which people from across the country traveled to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to commemorate the American Revolution. Many of the exhibitors chose to display cultural representations of 18th-century America, encouraging millions of people across the country to preserve the nation’s history. Architects were among those inspired, who looked to revitalize the design principles of colonial English and Dutch homes. This gradually gave way to a larger embrace of Georgian and Federal-style architecture, which focused exclusively on the country’s formative years. As such, structures built in the style of Colonial Revival architecture featured such components as pilasters, brickwork, and modest, double-hung windows. Symmetrical designs defined Colonial Revival-style façades, anchored by a central, pedimented front door and simplistic portico. Gable roofs typically topped the buildings, although hipped and gambrel forms were used, as well. This building form remained immensely popular for years until largely petering out in late-20th century. Nevertheless, architects today still rely upon Colonial Revival architecture, using the form to construct all kinds of residential buildings and commercial complexes.

-

Famous Historic Guests +

Henry Clay, 7th Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives and Senator from Kentucky, who is best remembered to history as the “Great Compromiser.”

Winfield Scott, 3rd Commanding General of the U.S. Army and war hero known as “Old Fuss and Feathers.”

Stephen A. Douglas, U.S. Senator from Illinois and presidential candidate who participated in the famous Lincoln-Douglas Debates.

Oscar Wilde, poet and playwright known for writing such works as The Importance of Being Earnest.

Millard Fillmore, 13th President of the United States (1850 – 1853)

Woodrow Wilson, 28th President of the United States (1913 – 1921)

Guest Historian Series

Nobody Asked Me, But…

Hotel History: Battle House Renaissance Mobile Hotel & Spa (1852), Mobile, Alabama

By Stanley Turkel, CMHS

The hotel is now known as the Battle House Renaissance Mobile Hotel. It was built in 1908 and replaced an earlier hotel that opened in 1852 and burned down in 1905. It was built by James Battle and his two half-nephews on the site of Andrew Jackson's military headquarters during the war of 1812. The first Battle House had famous guests such as Henry Clay, Jefferson Davis, Millard Fillmore, Winfield Scott and Stephen A. Douglas on the night that he lost the presidency to Abraham Lincoln. After the 1905 fire, the owners hired architect Frank M. Andrews who designed a new structure built of steel and concrete which opened in 1908.

President Woodrow Wilson was a guest in 1913 where he made his infamous statement that "the U.S. would never again wage another war of aggression". The hotel was owned and operated by the Sheraton Corporation until it was closed in 1974.

In 2003, the Retirement Systems of Alabama began restoration of the hotel along with the construction of an adjoining skyscraper, the RSA Battle House Tower. Both buildings opened in May 11, 2007 with a gala celebration attended by 600 guests.

Wikipedia described the renovated hotel as follows:

- “The eight-story building is steel frame with marble and brick facings. The hotel lobby features a domed skylight, dating back to 1908. The ceiling and walls are finished with elaborate plasterwork and are also painted using the trompe-l'oeil technique. The walls are painted with portraits of Louis XIV of France, George III of the United Kingdom, Ferdinand V of Castile and George Washington.”

The Trellis Room, Mobile's only Four-Diamond restaurant specializes in Northern Italian cuisine and features a full-view kitchen so patrons can watch the chefs prepare their meals. The Trellis Room ceiling contains a Tiffany glass skylight. The Crystal Ballroom is now used for social events such as parties, honorary dinners, weddings, meetings, and Mardi Gras balls.

In praise of Mobile's Mardi Gras history, a giant Moon Pie drops at midnight to ring in the New Year. Moon Pies are thrown from Mardi Gras floats each year and the giant confection replica is across the street from the Battle House.

In 2009, the Battle House was named "One of the Top 500 Hotels in the World" by Travel & Leisure Magazine. The Spa at the Battle House opened that same year. In 2010, the hotel became a member of the Historic Hotels of America, a program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

*****

About Stanley Turkel, CMHS

Stanley Turkel is a recognized consultant in the hotel industry. He operates his hotel consulting practice serving as an expert witness in hotel-related cases and providing asset management an and hotel franchising consultation. Prior to forming his hotel consulting firm, Turkel was the Product Line Manager for worldwide Hotel/Motel Operations at the International Telephone & Telegraph Co. overseeing the Sheraton Corporation of America. Before joining IT&T, he was the Resident Manager of the Americana Hotel (1842 Rooms), General Manager of the Drake Hotel (680 Rooms) and General Manager of the Summit Hotel (762 Rooms), all in New York City. He serves as a Friend of the Tisch Center and lectures at the NYU Tisch Center for Hospitality and Tourism. He is certified as a Master Hotel Supplier Emeritus by the Educational Institute of the American Hotel and Lodging Association. He served for eleven years as Chairman of the Board of the Trustees of the City Club of New York and is now the Honorary Chairman.

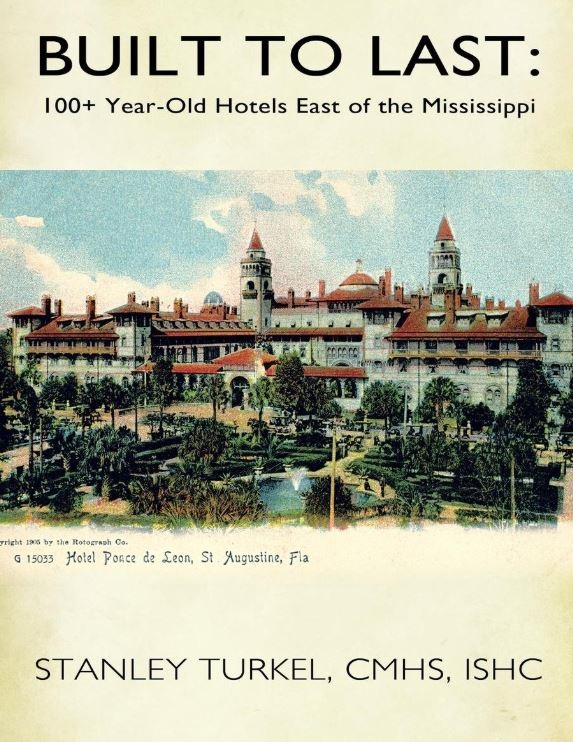

Stanley Turkel is one of the most widely-published authors in the hospitality field. More than 275 articles on various hotel subjects have been posted in hotel magazines and on the Hotel-Online, Blue MauMau, Hotel News Resource and eTurboNews websites. Two of his hotel books have been promoted, distributed and sold by the American Hotel & Lodging Educational Institute (Great American Hoteliers: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry and Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels East of the Mississippi). A third hotel book (Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels in New York) was called "passionate and informative" by the New York Times. Executive Vice President of Historic Hotels of America, Lawrence Horwitz, has even praised one book, Great American Hoteliers Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry:

- “If you have ever been in a hotel, as a guest, attended a conference, enjoyed a romantic dinner, celebrated a special occasion, or worked as a hotelier in the front or back of the house, Great American Hoteliers, Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry is a must read book. This book is recommended for any business person, entrepreneur, student, or aspiring hotelier. This book is an excellent history book with insights into seventeen of the great innovators and visionaries of the hotel industry and their inspirational stories.”

Turkel was designated as the “2014 Historian of the Year by Historic Hotels of America,” the official program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. This award is presented to an individual for making a unique contribution in the research and presentation of history and whose work has encouraged a wide discussion, greater understanding and enthusiasm for American History.

Works published by Stanley Turkel include:

- Heroes of the American Reconstruction (2005)

- Great American Hoteliers: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2009)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels in New York (2011)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels East of the Mississippi (2013)

- Hotel Mavens: Lucius M. Boomer, George C. Boldt and Oscar of the Waldorf (2014)

- Great American Hoteliers Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2016)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels West of the Mississippi (2017)

- Hotel Mavens Volume 2: Henry Morrison Flagler, Henry Bradley Plant, Carl Graham Fisher (2018)

- Great American Hotel Architects Volume 1 (2019)

- Hotel Mavens Volume 3: Bob and Larry Tisch, Curt Strand, Ralph Hitz, Cesar Ritz, Raymond Orteig (2020)

Most of these books can be ordered from AuthorHouse—(except Heroes of the American Reconstruction, which can be ordered from McFarland)—by visiting www.stanleyturkel.com, or by clicking on the book’s title.