Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

Discover The Pfister Hotel, a historic gem in downtown Milwaukee, which has been offering fine hospitality since its opening in 1893.

The Pfister Hotel, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 1994, dates back to 1893.

VIEW TIMELINE

The Pfister: History & Story

Explore the history of Milwaukee's Grande Dame, The Pfister Hotel in this short documentary that was produced for the 120th Anniversary of the historic destination.

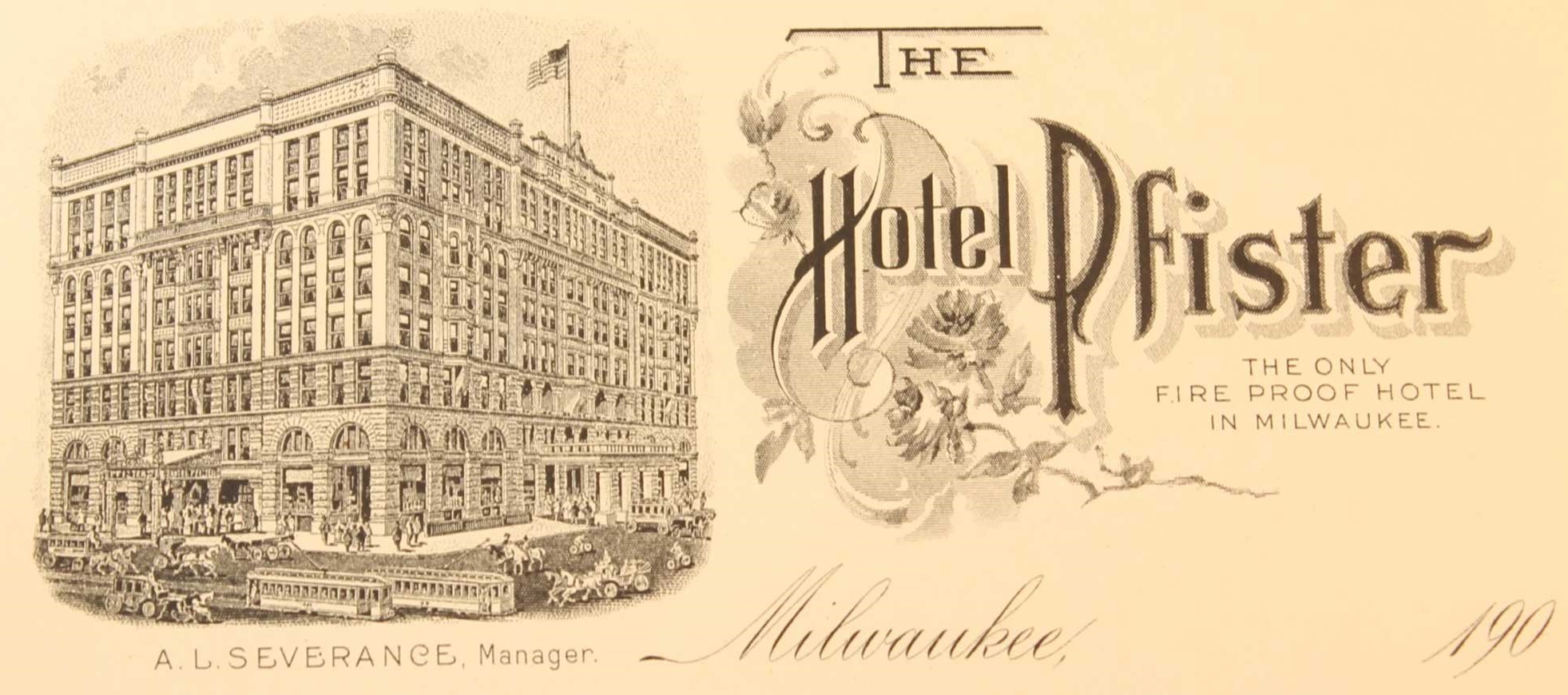

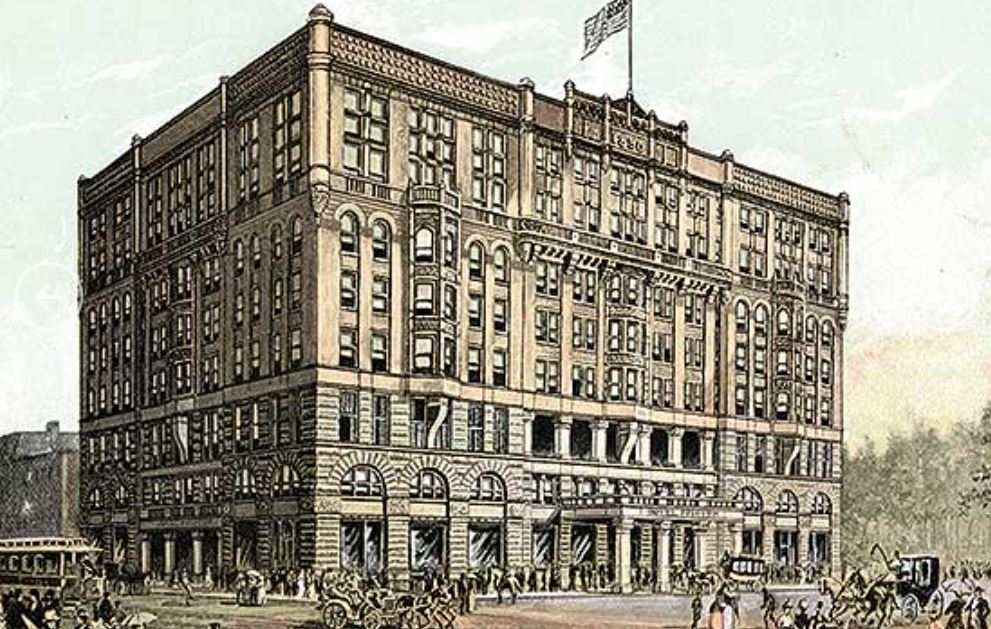

WATCH NOWA member of Historic Hotels of America since 1994, The Pfister Hotel was the product of businessman Guido Pfister. Before his entry into the hospitality industry, Guido Pfister—a German immigrant—originally made a name for himself through his Milwaukee-based tannery business, the “Guido Pfister Tanning Co.” Later renamed as the “Pfister and Vogel Leather Co.,” the company operated as one of the largest leather goods distributors in the Midwest. Quickly becoming a successful business leader, Guido decided to expand his interested into the country’s nascent tourist economy. He specifically envisioned creating a magnificent hotel in downtown Milwaukee that would attract people from all over the United States. With help from his own son, Charles, Guido put his plans into motion at the beginning of the 1890s. Together, the two men oversaw the creation of a gorgeous multistory structure that dominated the Milwaukee skyline. To craft its brilliant appearance, both Guido and Charles Pfister had relied upon the genius of architect Henry C. Koch. Koch proceeded to design a stunning Romanesque Revival façade that inspired all who saw it. The Pfisters had also spared no expense to create the beautiful hotel, spending over $1 million throughout the entire course of the project. The building boasted many groundbreaking features, such as fireproofing, electricity, and thermostat controls in every guestroom. In addition to its then-modern amenities, the hotel contained a formal dining room, a gentleman's lounge, and two billiard rooms—one each for women and men. An avid art collector, Charles Pfister even displayed much of his own collection throughout the structure. When construction finally concluded in 1893, “The Pfister Hotel” stood as one of the most gorgeous buildings throughout Milwaukee.

Nevertheless, the hotel struggled initially after its debut, as the Pfisters failed to make a profit. Thankfully, its grand character gradually made it a popular vacation hotspot, with many patrons even calling it the “Grand Hotel of the West.” True to Guido’s aspirations, affluent customers began reserving accommodations inside the building. In fact, one of the very first events that the hotel hosted was a massive convention for the Wisconsin Republican Party. Even some of the most powerful people in the nation visited at one point or another, starting with President William McKinley in 1897. Charles Pfister eventually began operating the hotel during the early 20th century, continuing his family’s stewardship over the business. At the height of Prohibition, Charles opened the modest pub, “English Room,” where he concocted a house specialty he named “Indian Punch.” Indian Punch would eventually build a huge following, incentivizing Pfister to bottle it for nationwide consumption. But after suffering a debilitating stroke, Pfister ultimately sold the business to his longtime friend and colleague Ray Smith. Then, in 1962, The Pfister Hotel was purchased by Ben Marcus, who had extensive plans to restore the structure back to its former glory. The work saw the building expanded considerably, primarily through the addition of new 23-story guestroom tower. An ornate bar called the “Crown Room” was its central fixture, which rapidly rose to become Milwaukee’s premier nightclub over the next few decades. Its live entertainment was its most appealing feature, hosting such renowned jazz musicians like Sarah Vaughan and Carmen McRae. Still under the watchful eye of the Marcus family today, The Pfister Hotel remains a historic gem in downtown Milwaukee.

-

About the Location +

Situated at the confluence of three rivers, Milwaukee is one of America’s most prominent metropolises. It is also among the most historic, as its heritage harkens back over hundreds of years. Numerous Native American societies had used the site of modern-day Milwaukee as a neutral hunting ground over millennia. Among the most prolific people to frequent the location were the Menominee, Potawatomi, and Ojibwe. Nevertheless, the Native Americans began to interact with French pioneers who had begun to colonize large swathes of the Mississippi River basin in the 17th and 18th centuries. While trading was incredibly active between the two cultures, a permanent Western settlement did not truly emerge in the area until the early 19th century. Scholars today credit the city’s founding to Solomon Juneau, who established a rustic log cabin along the eastern bank of the Milwaukee River. A French fur trader, Juneau had acquired the land via a grant owned by his father-in-law, Jacques Vieau, in 1818. Juneau subsequently began developing the area, eventually partnering with another pioneer named Morgan Martin to create an official village some two decades later. But Juneau and Moran were not without competition, however. Two other settlers—Byron Kilbourn and George H. Walker—arrived around the same time and constructed their own towns nearby. A fierce rivalry quickly manifested among the three communities, particularly between Juneau and Kilbourn. Thankfully, the three men were able to put aside their disagreements by uniting their settlements together to form one massive city called “Milwaukee.”

Milwaukee quickly emerged as a prominent economic center in the Midwest, even rivalling neighboring Chicago in size and importance for a time. One of the biggest factors driving this growth was largescale immigration of ethnic Germans to Milwaukee. Milwaukee’s new German demographic contributed greatly to its continued economic prosperity, forming the bedrock labor force for many new local industries ranging from agriculture to manufacturing. Brewing in particular became a thoroughly ingrained aspect of the city’s economy, turning Milwaukee into one of the nation’s leading beer distributors. But the presence of so many German expats had a profound impact on other elements of the community’s identity. Several neighborhoods within the Milwaukee quickly reflected the unique artistic aesthetics embraced by the different German subcultures that had relocated to the city. No where was this more apparent than in the architecture. Some of the buildings appeared to be so German in character that it made visitors feel as if were actually in Central Europe. A number of the German residents also brought their politics with them, too, creating a vibrant discourse that lasted for generations. The roots of this activity harkened back to the refugees who had fled to Milwaukee after fighting for liberal ideals during the Revolutions of 1848. This new political environment eventually created a movement known as “sewer socialism,” which spawned dozens of municipal building projects that created everything from community parks to sanitation systems. It even helped influence the emergence of modern American socialism, with Milwaukee serving as the first real stronghold for the ideology.

Despite the rise of other metropolitan areas in the Midwest, Milwaukee nonetheless continued to be one of its most celebrated destinations. Industry continued to dominate its economy, driven by the creation of many new business in fields like automobile manufacturing. Its proximity to Lake Michigan continued to make it an bustling port, while its many railway lines brought commerce from places as far away as the Pacific coast. Unfortunately, this prosperity came to an abrupt end during in the 1930s, when the Great Depression put nearly three-fourths of Milwaukee’s workers on the street. It would not be until the outbreak of the Second World War that the city’s economic fortunes were revitalized. The demand for vehicles, weapons, and ammunition gave a burst of new work to Milwaukee’s factories, which provided jobs to many. Its newfound success even attracted laborers from elsewhere in the country, including thousands of southern blacks. Indeed, nearly 15% of the city’s population was African American by the middle of the century. Today, Milwaukee very much remains a thriving metropolis. Not only does it still host a vibrant economy, it also is one of the most diverse communities in America. This historical diversity has attracted countless tourists, particularly the country’s invested cultural heritage travelers. Several of Milwaukee’s downtown buildings are even listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places or are identified as U.S. National Historic Landmarks. (One such area with a high concentration of historical structures is the East Side Commercial Historic District, of which The Pfister Hotel is a part.) Few places today are as fascinating a place to visit for a memorable vacation than Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

-

About the Architecture +

The Pfister Hotel shows some of the finest elements of Romanesque Revival architecture, too. Romanesque Revival-style architecture is a wonderful architectural style first appeared in North America in the middle of the 19th century, as design principles from both Rome and medieval Europe found a popular audience. Architects interested in specializing in Romanesque Revival-themed architecture specifically studied the works of Norman and Lombard engineers who were active in the 11th and 12th centuries. Structures created with the aesthetic are commonly defined by their pronounced round arches and round towers. Yet, those grand archways and towers were far less ostentatious than their historic counterparts located on the other side of the Atlantic. Romanesque Revival-style architecture also implemented squat columns, decorative wall carvings, and the extensive use of masonry. But architects would sometimes favor wood over bricks or stones due to financial concerns. The first wave of Romanesque Revival-style architecture impacted North America in the 1840s and 1850s, appearing in such cities like Washington, D.C. and Toronto. University College at the greater University of Toronto is one such example of a brilliant Romanesque Revival-inspired structure to emerge at the time. But the general public in both the United States and Canada did not fully embrace the aesthetic, preferring the tastes of Italianate and Gothic Revival architecture at the time. It was not until an American architect named Henry Hobson Richardson started using the form in the late 1800s that Romanesque Revival style finally became popular. A graduate from the renowned École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, Richardson developed numerous designs in places like New York City, Boston, and Detroit. His approach to Romanesque Revival style was somewhat different, as it also incorporated elements of medieval Mediterranean design principles. His vision of Romanesque Revival-style architecture was soon embraced by other architects, including those in neighboring Canada. Historians today largely refer to Richardson’s design philosophy as “Richardson Romanesque” architecture.

-

Famous Historic Guests +

Sarah Vaughan, winner of four Grammy Awards who is remembered today as “The Divine One.”

Carmen McRae, remembered as one of the most prominent jazz vocalists of the 20th century.

Al Jarreau, singer and musician widely celebrated for his critically acclaimed album, Breakin’ Away.

Henny Youngman, comedian and musician known of his one-liners like “Take my wife…please.”

Joan Rivers, comedian and actress remembered as one of the pioneers for women in comedy.

Luis Tiant, famous baseball pitcher who played 19 seasons with the Cleveland Indians and Boston Red Sox.

Thurman Munson, famous baseball catcher who played 11 seasons with the New York Yankees.

William F. Cody, Medal of Honor recipient and showman known to history as “Buffalo Bill.”

James Whitcomb Riley, poet who is know for works like “Little Orphant Annie” and “The Raggedy Man.”

William McKinley, 25th President of the United States (1897 – 1901)

Theodore Roosevelt, 26th President of the United States (1901 – 1909)

William Howard Taft, 27th President of the United States (1909 – 1913) and 10th Chief Justice of the United States (1921 – 1930)

Woodrow Wilson, 28th President of the United States (1913 – 1921)

Warren G. Harding, 29th President of the United States (1921 – 1923)

John F. Kennedy, 35th President of the United States (1961 – 1963)

Barack Obama, 44th President of the United States (2009 – 2017)