Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

- Call to Book: +1 800 678 8946 International|

- Email: Contact Us

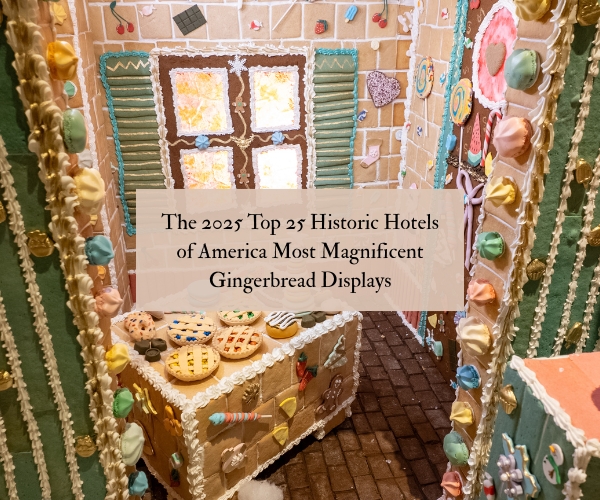

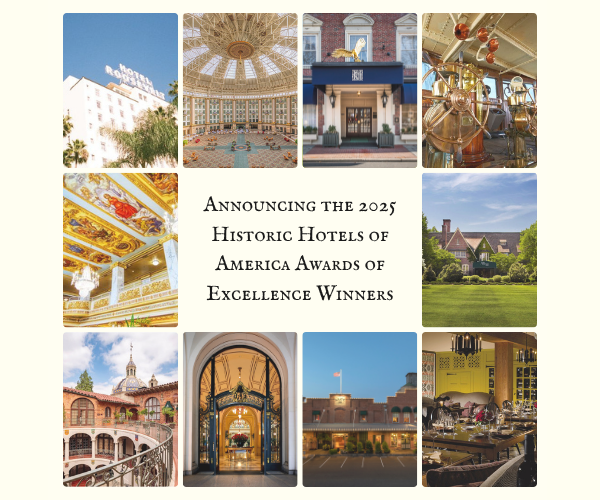

Closing Photo Gallery