Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history of casa monica in st. augustine

Discover Casa Monica in St. Augustine, FL, which was the vision of Henry Flagler, the co-founder of Standard Oil, who changed the name to Cordova.

Casa Monica Resort & Spa, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2001, dates back to 1888.

VIEW TIMELINE

Casa Monica Resort and Spa Tour

Explore the history and grounds of the Casa Monica in St. Augustine, FL and all it has to offer with CEO and Founder, Richard Kessler.

WATCH NOWA member of Historic Hotels of America since 2001, the Casa Monica Resort and Spa is St. Augustine’s most historic holiday destination. It first debuted in 1888, following a year of arduous construction work undertaken by Franklin W. Smith. Smith was a noted Civil War-Era abolitionist and social activist with a deep interest in Victorian architecture. A native Bostonian, he decided to build such a magnificent building because of the rise in Florida tourism at the end of the 19th century. The great Henry Flagler—who played a significant role in the state’s Gilded Age commercial development—sold the land to Smith as soon as he founded a spur to one of his local railways through St. Augustine.

Smith immediately went to work on his new structure, relying on the historically inspired design principles established in Moorish Revival and Spanish Baroque Revival architecture. He had long held a passionate fascination with Revivalist architectural forms, specifically Moorish Revival style. Smith’s nearby winter residence—Villa Zorayda—was the first Moorish Revival edifice in St. Augustine. The construction material was primarily poured concrete, of which Smith was a leading experimental authority. The resort hotel’s magnificent Sun Parlor room was its most celebrated space, as it was filled with fine architectural details.

Franklin W. Smith opened the Grand Dame as the “Casa Monica Hotel” on New Year’s Day. Yet, in just four months, Smith put the whole enterprise in serious financial trouble. Overwhelmed at the prospect of keeping the business afloat, he reached out to Flagler for relief. The railroad magnate purchased the entire facility from Smith for $325,000. Franklin W. Smith was incredibly desperate, selling to Flagler, “all fixtures, furnishings, silver, hardware, linen, bedding, parlor, hall, dining room, and kitchen furnishings and all other chattels.” Renamed Cordova Hotel, the business prospered under Flagler’s stewardship. It came as no surprise, as Flagler was one of the nation’s most successful hoteliers.

Alongside his close friend John D. Rockefeller, Flagler already owned two other destinations in St. Augustine—the Ponce de Leon Hotel (now Flagler College) and the Hotel Alcazar (currently the Lightner Museum). He also owned and operated several other successful hotels and resorts throughout Florida, having financed their construction to encourage travel along his various railroads. For the better part of the next three decades, the Cordova Hotel hosted all sorts of exciting fairs, galas, and charity events. Soon enough, the building became just as recognizable in St. Augustine as the iconic Castillo de San Marcos. Its renown inspired the legendary travel agent, Ward G. Foster, to establish the headquarters of his soon-to-be-famous travel agency, “Ask Mr. Foster,” inside the building.

The success of the business inspired Henry Flagler to connect the Cordova Hotel to the nearby Hotel Alcazar via a bridge in 1902. Uniting the two ventures into one business, the Cordova Hotel soon became known as the Alcazar Annex. The Hotel Alcazar and the Alcazar Annex remained in his family for several years, even after Flagler’s death in 1913. But the Hotel Alcazar became a victim of the Great Depression, with Flagler’s descendants foreclosing on the entire destination in 1932. The Alcazar Annex fell into a state of dilapidation, with much of its historical architecture deteriorated. Flagler’s historic bridge was torn down.

Having sat dormant for 30 years, the St. Johns County Commission voted to purchase the facility for use as the county courthouse. The renovations to restore the ailing structure took nearly six years to complete, finally opening as the St. Johns County Courthouse in May of 1968. Serving in that capacity for the next three decades, the revitalized historical structure stood once again as a cherished local landmark. A notable feature included inside the courthouse involved murals painted by the artist Hugo Ohlms, whose work also appeared in the Ponce de Leon Motor Lodge and the neighboring St. Benedict Catholic Church. Another fascinating aspect was the stained-glass door panels at the front entrance that displayed the scales of justice.

In February 1997, Richard Kessler—who had previously worked with the Days Inn hotel chain and later founded the Kessler Collection— fell in love with the building’s gorgeous historical architecture. Kessler purchased the building from the St. Johns County government for $1.2 million. He immediately began remodeling the historic structure, transforming it back into a magnificent resort hotel. Kessler hired architect Howard W. Davis to spearhead the redesign, which focused on saving the building’s Moorish Revival-style architecture. Taking two years to complete, the brilliant structure opened as the Casa Monica Hotel in the winter of 1999.

It is now the Casa Monica Resort & Spa and continues to serve as one the main destinations within the Kessler Collection. The Casa Monica Resort & Spa is one of St. Augustine’s most celebrated holiday destinations. Its spectacular service and stunning amenities separated this remarkable resort hotel from its competitors. Dozens of illustrious guests have stayed at the reborn Casa Monica Resort & Spa, including South African civil rights activist Desmond Tutu, King Juan Carlos I of Spain, and former U.S. President Bill Clinton. Few places in Florida are as spectacular than this wonderful, historic resort.

-

About the Location +

St. Augustine, Florida, bears the distinction of being the oldest continuously inhabited city in the continental United States. Its history is both rich and extensive. While Native Americans frequently passed through the region for millennia, the first European settlers arrived at the beginning of the 16th century. The Europeans were Spanish conquistadors led by the famous explorer Juan Ponce de León. Landing along the shoreline in 1513, Juan Ponce de León traveled to the Floridian coast in hopes of discovering the mythological Fountain of Youth. Even though Ponce did not locate his coveted prize, he managed to claim the territory in the name of the joint Spanish monarchs, King Ferdinand II and Queen Isabella I.

But Spain’s sovereignty over the region was eventually challenged by the French in 1564, who subsequently constructed a massive citadel called Fort Caroline at the mouth of the St. Johns River. Undeterred, the Spanish Crown sent Pedro Menéndez de Avilés at the head of a massive fleet to destroy the upstart settlement. Pedro Menéndez de Avilés ships first sighted land on August 28, 1565, which coincided with the feast day for St. Augustine of Hippo. They came ashore some 33 miles to the south of Fort Caroline and established their own military outpost. In honor of St. Augustine, Pedro Menéndez de Avilés called the nascent village San Agustín. (St. Augustine was the patron saint of Pedro Menéndez’s hometown of Avilés.)

Menéndez made peace with a local band of the Timucua Indians and billeted his forces inside one of their palisaded communities near Matanzas Bay. From the village, Menéndez and his fellow colonists struck at Fort Caroline, killing nearly all the settlers inside. With the immediate French threat removed from Florida, Pedro Menéndez de Avilés intended for San Agustín to serve as a base for further colonial exploration into the interior. His plans were hampered by French and English pirates and various Native American tribes that were disaffected with the behaviors of the Spanish.

The climax of the hostilities came when Sir Francis Drake successfully sacked San Agustín in 1586. Nevertheless, the colonial settlement endured for decades, as the inhabitants became better at resisting the attacks against their community. In 1672, the local authorities oversaw the construction of the imposing Castillo de San Marco. They hoped it would deter any future assaults on San Agustín by either land or sea. Even though San Agustín remained relatively undeveloped economically, it did manage to attract some settlers from across the world.

Among them were freed blacks who had escaped from the plantations in English—and later British—controlled Georgia and South Carolina. One Spanish colonial governor formally organized a special community of ex-slaves jus to the north of San Agustín to help serve in its defense. The colonial subjects of the two southern most British colonies became Spanish Florida’s most determined enemy. Their residents played a prominent role in the city’s capture during the Seven Years’ War, in which Spain surrendered all of Spanish Florida to the United Kingdom. The British subdivided the territory’s administration, with San Agustín serving as the capital for the newly created Colony of East Florida.

British sovereignty over San Agustín proved brief, as Great Britain was forced to surrender control over Florida back to Spain following its defeat during the American Revolutionary War.

For the next five decades, the city was a Spanish possession. Still, Florida remained a sparsely populated territory largely occupied by bands of Native Americans, as well as small outposts of soldiers in places like San Agustín. The young United States had taken a particular interest in Florida and had worked closely with the Spanish government to obtain its land. American settlers began to illicitly settle the territory, causing border friction with the local Seminole tribe. Some military leaders like General (and future U.S. President) Andrew Jackson conducted illegal invasions to stop the Seminole from attacking those isolated villages. With the kingdom teetering on economic collapse due to the recent Napoleonic Wars, Spain ceded Florida to the United States in 1821.

Florida became an American territory with General Jackson serving as its first federal governor. San Agustín itself was anglicized to St. Augustine and became a small, important, port city. It no longer served as Florida’s capital, though, as Tallahassee further to north was given that honor. St. Augustine’s imposing costal fortress remained integral to both the city and Florida, as it served as the primary defense mechanism for the region. Renamed as “Fort Marion,” the structure held captive Seminole during the Second Seminole War of 1835 to 1842. It later fell under Confederate occupation in 1861, when Florida—now a state—seceded from the Union at the start of the American Civil War. Since Fort Marion was a federal military installation, local rebel militia cells targeted the ancient citadel early in the conflict. Their time inside the fort was brief, as the U.S. Navy recaptured the facility in March of 1862. It remained under Union rule for the remainder of the war.

When the American Civil War finally came to an end in 1865, Fort Marion started to fall out of use. It was only used three more times during its lifetime, in which the federal government used it to house Plains Indians and Apaches who had resisted the U.S. Army. Its final assignment saw it ironically serve as a prison for captured Spanish soldiers during the Spanish-American War of 1898. By 1900, Fort Marion had been removed from the War Department’s active duty rolls. St. Augustine had long lost its identity as an exclusive military outpost.

During the 1880s, railroad tycoon Henry Flagler and his business partner, John D. Rockefeller, had arrived in St. Augustine. Flagler and Rockefeller had previously joined forces to create the mighty American company Standard Oil. Now, the two wanted to grow their affluence by expanding the nation’s railroad network into the Deep South. They also realized their prospective railroad network could subsidize passenger traffic into Florida, which had a warm tropical climate that many northerners would find appealing in the winter months. As such, Flagler and Rockefeller extended a segment of their Florida East Coast Railway into St. Augustine and immediately began creating several extravagant hotels to incentivize travel along the route.

One of the magnificent buildings that Flagler and Rockefeller developed were the Hotel Alcazar and the Ponce de León Hotel. Flagler himself operated a few additional business ventures on his own, including the Casa Monica Resort & Spa, which operated as the Cordova Hotel at the time. As the 20th century dawned, the City of St. Augustine was among Florida’s most visited holiday destinations. Today, the city continues to maintain that status. Its amazing history is a huge reason why its popularity has persisted. Few cities in the United States can claim to possess such a heritage. Much of St. Augustine’s historical buildings remain intact, with some even recognized by Washington as National Historic Landmarks. Among those structures are the Ponce de León Hotel—currently part of Flagler College—and Fort Marion, which now goes by its original name, the Castillo de San Marco.

-

About the Architecture +

When amateur architect William F. Smith first designed the Casa Monica Resort and Spa in 1887, he used a wonderful blend of Moorish Revival and Spanish Baroque architectural styles. Moorish Revival, also referred to as Neo-Moorish, was one of the Revivalist architectural forms from the 19th century that sought to preserve earlier examples of historical architecture. Moorish Revival architecture was one of the first Revivalist styles, emerging throughout western and central Europe in the early 1800s. It reached the United States during the 1830s and became popular shortly after the American Civil War. Moorish Revival-style remained prevalent among Americans at the turn of the century, before disappearing during the Great Depression. While most Revival styles born in the Victorian Era copied earlier Western design aesthetics, Moorish architecture largely borrowed its elements from the Moors of North Africa. Muslims of Berber origin, the Moors had conquered almost all of the Iberian Peninsula by the dawn of the Early Middle Ages.

While their civilization was largely driven out of the region by the 15th century, many aspects of their culture endured for generations. Perhaps one of the Moors greatest legacies in Spain and Portugal were their grand architectural designs. Influenced by Islamic design principles further west in the Middle East, the Moors created brilliant edifices that embraced the concepts of rhythmic linear patterns, vegetative design, and elaborate geometric shapes. A combination of wood, stucco, and tiling—most notably zellij—constituted the buildings materials, although contemporary architects added more modern resources when attempting to emulate the design in the 1800s. One of the greatest components to Moorish buildings involved the horseshoe arch, which consisted of a perfect curve that bulged outward from the base. Furthermore, the Moors decorated their structures with onion-shaped domes that were generally topped with a pointed spire.

Even though the Casa Monica Resort & Spa is celebrated for its Moorish Revival-style architecture, it also contains aspects of Spanish Baroque-themed design aesthetics. Baroque architecture appeared throughout Europe in the early 17th century, with the first examples emerging across the Italian Peninsula. The Catholic Church specifically introduced the form as a means of combating the cultural influences of the Reformation and its various Protestation denominations. Meant to inspire intellect, the architectural style was defined by its ostentatious features that evoke awe and amazement.

It broke from the earlier architectural principles of the Renaissance, only borrowing the period’s use of grand domes and colonnades. Yet, those structures were often made to look extravagant in nature, using their curvaceous qualities to give a sense of undulation to those gazing below. Complex floorplans founded on similar characteristics appeared throughout the space, which made use of circular geometric shapes like the oval to repeat the effect. They were also filled with an array of rich surface treatments, twisting elements, and gilded sculptures. Ceilings in particular displayed grand pieces of artwork in the form of the quadrature or the trompe-l’oeil. When the style finally crossed over the Pyrenees, Spanish architects added their own variations.

At first, the unique Spanish take on Baroque style was simpler due to the influence of architect Juan de Herrera and his refined classicism. But the architecture became increasingly more flamboyant to appeal directly to the senses. This change was faciliated by the Churriguera family, who had initially designed altars and retables for the Catholic Church. Put off by the Herrera’s legacy, the Churrigueras developed a subset of the Baroque movement that increased the decorations on a building’s façade. The most prevalent features on every one of their structures involved the use of the Solomonic column and composite order. In later years, an estipite was added to the design. Celebrated as Churrigueresque, the form appeared prominently in the Spanish cities of Salamanca and Madrid, as well as Spain’s many imperial colonies.

Today, the hotel’s renovated exterior from the corner of Cordova Street has a stately stone column rising to the third story, supporting a circular balcony with a unique doorway built into a corner. From here the two wings of the hotel extend, one down Cordova Street and the other making up the west façade on King St. The lower row of windows is framed by balconies like those found in Seville. This style was designed by Michael Angelo, who called them “kneeling balconies” due to their protruding base which allowed the faithful to kneel during the religious processions of the day. The ground floor of the original 1888 hotel included a ladies-only Writing Room and a Drawing Room, now Reubel’s Jewelry Store and The Coleman Art Gallery, respectively.

-

Famous Historic Guests +

Desmond Tutu, South African theologian and renowned anti-apartheid activist.

Reverend C.T. Vivian, civil rights activist and confidant to Martin Luther King Jr.

Juan Carlos I, King of Spain (1975 – 2014)

Sofía, Queen consort of Spain (1975 – 2001) and Princess of Greece and Denmark

Bill Clinton, 42nd President of the United States (1993 – 2001)

-

Film, TV and Media Connections +

Illegally Yours (1988)

Guest Historian Series

Nobody Asked Me, But…No. 167;

Hotel History: Casa Monica Resort & Spa (1888), St. Augustine, Florida*

By Stanley Turkel, CMHS

The Casa Monica, one of the oldest hotels in the United States, was built by Franklin W. Smith, an idealistic reformer who made his fortune as a Boston hardware merchant. He was an early abolitionist, author and architectural enthusiast who proposed transforming Washington, D.C. into a "capital of beauty and cultural knowledge." He was a major founder of the YMCA and a supporter of the 1860 election of Abraham Lincoln.

Henry M. Flagler sold Smith the land on which to build the Casa Monica Hotel in 1887. The Casa Monica is an impressive five-story structure with 100-foot towers on each end topped with tile roofs. There are unique architectural features such as turrets, balconies, parapets, ornate railings, cornices, arches, and battlements on the exterior. Smith utilized an experimental process for making concrete blocks using crushed coquina along with Portland cement. The hotel opened on January 1, 1888 with 138 rooms including 14 duplex suites with up to three bedrooms. The architectural style was Moorish Revival and Spanish Baroque Revival of which Smith was a pioneer promoter.

Four months later, Smith ran into financial difficulties and sold the hotel to Henry Flagler who changed the name to the Cordova Hotel. While the hotel flourished under Flagler's management, he built a bridge between the Cordova and merged it with his adjacent "enlarged and redecorated" Alcazar Hotel. Because of the Great Depression, the hotel closed in 1932 and in 1945 the bridge was torn down. In 1962, the St. John's County Commission purchased and renovated the Cordova Hotel for use as a county courthouse. In 1964, the lobby housed police dogs that were used against civil rights demonstrators during the mass campaign led by Dr. Martin Luther King that resulted in the passage of the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The famous travel agency “Ask Mr. Foster” had its headquarters in the hotel. It was started by Ward G. Foster of St. Augustine, became a national business and was owned for a time in the 20th century by Peter Ueberroth, once Commissioner of Baseball.

In February 1997, Richard Kessler, formerly an executive with Days Inns of America, purchased the building from St. John’s County for $1.2 million and began to remodel the building to once again become a hotel. The county Tax Collector’s office and Property Appraiser’s office were given until 1998 to relocate. The renovation was completed in less than two years and opened in December 1999 under the original name of “Casa Monica Hotel” (the name came from Saint Monica, the North African mother of St. Augustine, Bishop of Hippo, for whom the Ancient City is named). Richard Kessler and architect Howard W. Davis decided to keep the historic Moorish Revival style of the hotel. Artist Tina Guarano Davis painted the Moorish-style woodwork in the hotel lobby. The Casa Monica sign on the Cordova Street side of the hotel covers over an earlier sign for the St. Johns County Courthouse. The huge flagpole on top of the hotel is actually a lightning rod.

Among the notable guests in the hotel since it reopened have been Archbishop Desmond Tutu, South African Nobel Peace Prize winner and anti-apartheid crusader, and Rev. C.T. Vivian, civil rights leader and co-worker with Martin Luther King in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, as well as the King and Queen of Spain during their visit to St. Augustine in 2001.

The Casa Monica Hotel is a member of Historic Hotels of America, an official program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

*****

About Stanley Turkel, CMHS

Stanley Turkel is a recognized consultant in the hotel industry. He operates his hotel consulting practice serving as an expert witness in hotel-related cases and providing asset management an and hotel franchising consultation. Prior to forming his hotel consulting firm, Turkel was the Product Line Manager for worldwide Hotel/Motel Operations at the International Telephone & Telegraph Co. overseeing the Sheraton Corporation of America. Before joining IT&T, he was the Resident Manager of the Americana Hotel (1842 Rooms), General Manager of the Drake Hotel (680 Rooms) and General Manager of the Summit Hotel (762 Rooms), all in New York City. He serves as a Friend of the Tisch Center and lectures at the NYU Tisch Center for Hospitality and Tourism. He is certified as a Master Hotel Supplier Emeritus by the Educational Institute of the American Hotel and Lodging Association. He served for eleven years as Chairman of the Board of the Trustees of the City Club of New York and is now the Honorary Chairman.

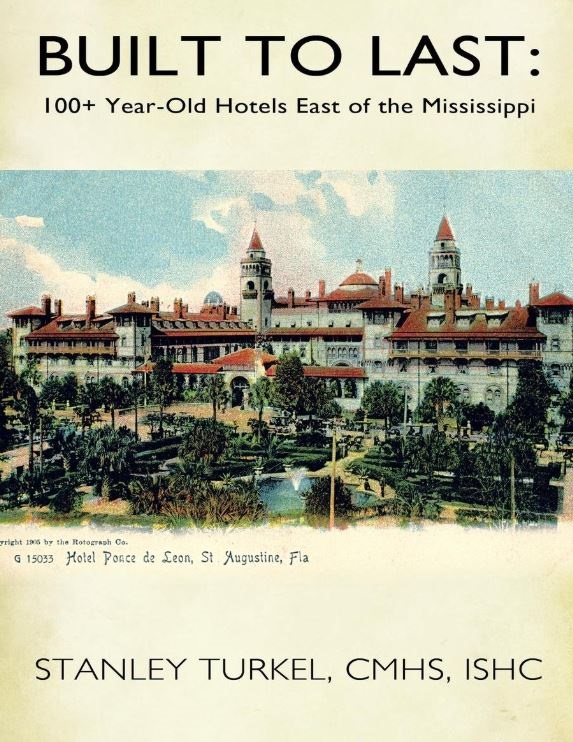

Stanley Turkel is one of the most widely-published authors in the hospitality field. More than 275 articles on various hotel subjects have been posted in hotel magazines and on the Hotel-Online, Blue MauMau, Hotel News Resource and eTurboNews websites. Two of his hotel books have been promoted, distributed and sold by the American Hotel & Lodging Educational Institute (Great American Hoteliers: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry and Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels East of the Mississippi). A third hotel book (Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels in New York) was called "passionate and informative" by the New York Times. Executive Vice President of Historic Hotels of America, Lawrence Horwitz, has even praised one book, Great American Hoteliers Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry:

- “If you have ever been in a hotel, as a guest, attended a conference, enjoyed a romantic dinner, celebrated a special occasion, or worked as a hotelier in the front or back of the house, Great American Hoteliers, Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry is a must read book. This book is recommended for any business person, entrepreneur, student, or aspiring hotelier. This book is an excellent history book with insights into seventeen of the great innovators and visionaries of the hotel industry and their inspirational stories.”

Turkel was designated as the “2014 Historian of the Year by Historic Hotels of America,” the official program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. This award is presented to an individual for making a unique contribution in the research and presentation of history and whose work has encouraged a wide discussion, greater understanding and enthusiasm for American History.

Works published by Stanley Turkel include:

- Heroes of the American Reconstruction (2005)

- Great American Hoteliers: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2009)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels in New York (2011)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels East of the Mississippi (2013)

- Hotel Mavens: Lucius M. Boomer, George C. Boldt and Oscar of the Waldorf (2014)

- Great American Hoteliers Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2016)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels West of the Mississippi (2017)

- Hotel Mavens Volume 2: Henry Morrison Flagler, Henry Bradley Plant, Carl Graham Fisher (2018)

- Great American Hotel Architects Volume 1 (2019)

- Hotel Mavens Volume 3: Bob and Larry Tisch, Curt Strand, Ralph Hitz, Cesar Ritz, Raymond Orteig (2020)

Most of these books can be ordered from AuthorHouse—(except Heroes of the American Reconstruction, which can be ordered from McFarland)—by visiting www.stanleyturkel.com, or by clicking on the book’s title.