Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

Discover Grand Hotel Golf Resort & Spa, which was involved in the Battle of Mobile Bay during the Civil War and led by Admiral Farragut.

Grand Hotel Golf Resort & Spa, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2011, dates back to 1847.

VIEW TIMELINE

Hotel With A Past: Grand Hotel Golf Resort & Spa

The hotel celebrates its connection to its Civil War history every day, connecting resort guests to their past with talks and ceremony.

WATCH NOWA member of Historic Hotels of America since 2011, the Grand Hotel Golf Resort & Spa is among the most luxurious places to visit along the Gulf Coast. Its history harkens back decades, as it was founded by F.H. Chamberlin in 1847. The original hotel structure that Chamberlin built was a disjointed two-story hotel that extended for some 100-feet along the coastline of Point Clear, Alabama. Both floors only featured 40 guestrooms and a shaded gallery that offered brilliant views of the ocean nearby. Two additional structures sat next to the main building, as well. The first building housed a rustic dining space, while the second—called the “Texas”—served as the home to a bar. The construction project was one of the largest in the area to date, with dozens of boats from Mobile transporting wood from places further north in large quantities. In some respects, the convoy looked to be endless as it continuously dropped off men and material. By all accounts, the Texas was among the most exclusive venues in the greater Mobile area. Contemporary news articles stated that high-stakes poker games occurred frequently inside the bar among the area’s wealthy merchants and planters, who traded tales of gossip and intrigue regularly. The business was so successful that Chamberlin acquired a fourth building to act as overflow housing. That structure was called the “Gunnison House,” which had previously functioned as a summer retreat for a local affluent family.

Chamberlin’s nascent resort abruptly experienced a sharp decline in business when Alabama seceded from the Union in early 1861. The state had become one of the founding members of the Southern Confederacy, with Mobile emerging as one of its most important commercial centers. When the two sides formally began fighting one another later that summer, the city quickly found itself the target of a massive blockade by the United States Navy. Over time, local sailors began running blockade runners past the northern ships in an attempt to ferry goods to foreign markets across the Gulf to Havana, Cuba. The continuous economic threat that the blockade runners posed eventually inspired the great Admiral David Farragut to directly target Mobile for an attack in August of 1864. While combat actions around the city lasted for nearly a month, the main fighting transpired on August 5. A small flotilla of rebel warships and coastal artillery batteries viciously dueled with Farragut’s much larger invasion force, which attempted to sail straight up Mobile Bay in the direction of the heavily fortified Fort Morgan. As the fighting raged all along the coastline, a few cannon shells landed in the vicinity of Chamberlin’s nascent resort. One piece of ordnance actually crashed through the Gunnison House, although the building was largely left intact. After the battle, local Confederate officers used the destination as a hospital for soldiers wounded during the recent campaign. In fact, some 300 rebel soldiers died while receiving care onsite. A grave for those men is still located on the grounds, called the “Confederate Rest Cemetery.” (In 2008, the staff at the Grand Hotel Golf Resort & Spa started commemorating the battle by firing a cannon as a military salute to those who died during the battle.)

Chamberlin resumed operating the destination as the private resort as soon as the fighting had stopped. His business grew in popularity yet again, transforming the community of Point Clear into one of Alabama’s most prestigious vacation hotspots. Streamliners began providing direct service to the hamlet, dropping off countless people on Chamberlin’s docks seemingly every day. Soon enough, interested guests from New Orleans and other cities throughout the Gulf region were making the trek to Chamberlin’s resort. But tragedy struck in 1871, when a steamship known as the Ocean Wave exploded just beyond the resort’s pier. Several passengers perished as a result of the catastrophe with many more injured. Most of those who were hurt received care inside the Texas Bar, which Chamberlin had turned into a makeshift medical facility. Shortly thereafter, Captain H.C. Baldwin purchased the location and immediately went about revitalizing the entire site. He quickly determined that the resort’s main building had become too dated and ultimately built a much larger hotel facility. While it resembled the earlier structure, the Baldwin’s new construct was three times its size! Debuting as the “Grand Hotel” in 1875, it contained sixty suites that offered the best amenities of the age. Winter rates were set at two dollars a day, rising to a total of 40 dollars for a whole month. As such, the resort flourished. And when Baldwin died a few years later, his son-in-law, George Johnson, continued to ensure that his successful policies remained in place. By the 1890s, guests from throughout the Deep South knew of the Grand Hotel. Many in the region even took to calling the destination as “The Queen of Southern Resorts.”

In 1901, George Johnson decided to sell the Grand Hotel—including the 250 acres—to James Ketchum Glennon. But Glennon’s acquisition of the resort marked the beginning of a prolonged period of decline that lasted well into the mid-20th century. It started with two hurricanes that greatly damaged the resort in 1906 and 1916, respectively. Despite being discouraged about the two incidents, Glennon renovated the Grand Hotel both times. It managed to briefly resumed its status as Alabama’s premier beachside retreat during the Roaring Twenties, until the Great Depression sapped whatever economic momentum it had managed to create. Frustrated, Glennon sold the Grand Hotel to Edward A. Roberts, who was the chairman of the Waterman Steamship Corporation. The resort had become so badly rundown that Roberts instructed his employees to demolish most of the structures. What remained he had thoroughly restored. Roberts also constructed a new magnificent structure that served as the main building of the resort straight through to the present. It originally debuted with 90 amazing guest accommodations and modern air-conditioning. He also commissioned the creation of several cottages a few months later, as well, which functioned as exclusive bungalows for the resort’s upscale clientele. Yet, the country’s entrance into World War II largely put a stop to Roberts’ renovations, as the War Department petitioned the hotelier to lease the facility for use by the U.S. Army Air Corps. Roberts agreed, leasing the entire resort with the sole stipulation that the soldiers garrisoned onsite would not walk through the facility while wearing their combat boots. The Grand Hotel subsequently helped the military train servicemen to operate mobile air depots throughout the Pacific Theater, as it inched closer to the Home Islands of Japan. Much of the training was done under a top secret program that the War Department referred to as “Operation Ivory Soap.” See the section “Famous Historical Events” below for more information.

The Grand Hotel reopened, becoming once more “The Queen of Southern Resorts.” Roberts continued improving the new iteration of the Grand Hotel, installing the resort’s famed Azalea and Dogwood golf courses toward the end of the 1940s. But in 1955, a massive corporate conglomerate purchased the location, eventually turning it over to a North Carolina businessman named Malcom McLean a decade later. He, in turn, sold it to his brother, James K. McLean. Recognizing that Roberts’ golf courses were now drawing ever increasing numbers of guests to the Grand Hotel, McLean subsequently developed a 50-guestroom extension onto the main building. McLean also created additional accommodations in the form of 10 luxurious cottages, as well as the spectacular Bay House. He even created a brilliant 9-hole golf course to deal with overcrowding on the other two 18-hole facilities. When Hurricane Frederick wrought some serious damage to the grounds in 1979, the owners of the Grand Hotel decided to seek Marriott International for help. Marriott eventually purchased the resort and spent the remainder of the 1980s thoroughly repairing and renovating the resort. It added nearly 200 more accommodations, as well as the North Bay House and the Mariana Building. The company also made the difficult decision to demolish the devastated Gunnison House, constructing a new Grand Ballroom in its place. In all, Marriott International spent nearly $50 million restoring the Grand Hotel back to its former glory. Now this spectacular seaside destination is truly the “Queen of Southern Resorts.”

-

About the Location +

The nearby city of Mobile is one of the most historic places in the nation. The site of the present city was originally explored by the Spanish as early as the beginning of the 16th century, shortly after Christopher Columbus established the first European colony in the “New World.” Yet, the first permanent European settlers arrived nearly two centuries later, when Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville led a group of French colonists several miles up the Mobile River in 1702. Here, he established “Fort Louis de la Louisiane” on behalf of the Colonial Governor of French Louisiana—who happened to also be his brother—Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville. As disease began ravaging the population, Bienville instructed the colonists to relocate downstream to the river’s confluence with Mobile Bay. They erected a new fort in 1711 and small community quickly emerged over the next several decades. The small village soon became known as “Mobile,” named for the “Maubilla” Indians that once lived nearby. Even though the colonial outpost struggled to grow in size, its functioned as the capital of Colonial Louisiana during the first years of its existence. But when war erupted between France and Spain in 1719, Bienville decided to relocate the colony’s administrative offices further west to the emerging settlement of Biloxi. Meanwhile, Mobile effectively served as a military outpost between the two warring kingdoms, with the local colonial populations fighting against each other. Mobile eventually found its footing within the French Empire, acting as a major commercial trading center with the local Native Americans. The British eventually seized the entirety of Mobile Bay, though, after the Seven Years’ War, when France ceded it to Great Britain. The area subsequently joined the British colony of “West Florida,” until it was given to the Spanish following the American Revolution.

Mobile and the rest of the modern Alabama coastline continued to be a part of Spanish-controlled Florida until the War of 1812. An American army stationed in New Orleans invaded the region under the pretense that its merchants were selling arms to native tribes allied with the British. But the United States had long disagreed over the exact location of Spanish Florida’s western border, which further incentivized the Americans to seize the region. Spain ultimately relented, signing the territory over to the United States. Mobile and the land surrounding Mobile Bay joined the Mississippi Territory, although that union proved to short-lived. The territory subsequently split in two, with the western half becoming the state of Mississippi in 1817. The eastern portion bordering Georgia joined the nation as “Alabama” two years later. While the state capital was founded in Montgomery to the north, Mobile emerged as Alabama’s most prosperous city. It rapidly became one of the busiest port cities in the South, second only to New Orleans in its affluence. In fact, by the 1850s, Mobile was one of the top five seaports in the whole nation. Its commercial importance eventually played a major role during the American Civil War of the mid-19th century, when the newly formed Confederacy relied upon its maritime commerce to supply its nascent war effort. The Union eventually attempted to blockade the city, but ships known as blockade runners occasionally managed to evade capture. Mobile’s significance to the rebel war effort became all the more vital when New Orleans was occupied by northern soldiers in early 1862. Eventually, the Lincoln administration sought fit to seize Mobile itself, instructing Admiral David Farragut to attack the city. While the city itself never fell to the North, its surrounding harbor was effectively captured by Farragut’s command following the Battle of Mobile Bay in 1864.

After the war, Mobile struggled to reassert itself as one of America’s preeminent ports, eventually going bankrupt in 1879. But its economy gradually improved, especially after local ship captains began importing tropical fruits alongside their normal exports of lumber and cotton. The maritime trade received a much needed boast, though, in 1914, when construction finally ended on the Panama Canal, allowing the city’s merchants to trade more easily with markets on the other side of the world. Later developments emerged, too, that helped the city’s naval commerce to return, including the creation of the Intracoastal Waterway, as well as the Alabama State Docks. Industrialization also took root in the city around the same time, giving rise to factories that contributed greatly to the development of a localized shipbuilding industry. Perhaps the most prominent shipbuilding company to appear in Mobile was the Alabama Drydock and Shipbuilding Company, which constructed countless cargo vessels during World War II. Another prominent company was a subsidiary of the Gulf Shipbuilding Corporation called the Waterman Steamship Corporation. It subsequently built freighters, destroyers, and minesweepers in the war, too. Other major industries appeared by the middle of the century, including chemicals, textiles, and vehicle components. Paper products also became a central fixture in the city’s economy, with the Scott Paper Company and International Paper employing a large segment of its population. But the time period also saw the emergence of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, in which racial equality became a major aspect of the city’s political landscape. While Mobile had been more open to desegregation than most other southern cities, its education system remained separated on the basis of race well after the U.S. Supreme Court had ruled the practice unjust. In 1963, three African American students sued the Mobile County School Board in federal court, citing the majority decisions presented in Brown v. Board of Education The federal court ruled in their favor, forcing Murphy High School to completely desegregate by the next school year.

Today, Mobile is a vibrant, modern city filled with all sorts of outstanding cultural attractions to visit. Among the most popular destinations in the area are GulfQuest National Maritime Museum, Gulf Coast Exploreum Science Center, and a colonial citadel named “Fort Conde.” Its shoreline is also home to Battleship Memorial Park, where the famed World War II-era battleship, the USS Alabama, acts as a museum. Modern Mobile is also home to one of the earliest authentic Mardi Gras festivals in the whole United States, rivaling New Orleans in its grandiose character. Its downtown still reflects much of its historic character, as evidenced by the Victorian-era mansions and cottages that line its historic Oakley Garden District. To the west, even more historic buildings reside within the fabulous Old Dauphin Way District. Few places are truly better in the Gulf Coast for a historically-inspired vacation than the brilliant city of Mobile.

-

About the Architecture +

The Grand Hotel Golf Resort and Spa possesses a unique architectural style that can best be described as “eclectic.” Dating to the late 19th and early 20th centuries, historians today consider “eclecticism” to be part of a much larger movement to fuse together a variety of historical designs. Earlier in the 1800s, architects—particularly those in Europe—decided to rely upon their own loose interpretations of historical architecture whenever they attempted to replicate it. Such a practice appeared within such styles as Gothic Revival, Italianate, and Second Empire architecture. But at the height of the Gilded Age, those architects decided to use historic architecture more literally when developing a building. A few architects went a step further by combining certain historical styles together to achieve something uniquely beautiful. And in some cases, those individuals felt inspired to add a new historical form onto a building that they were renovating—just like the Grand Hotel Golf Resort & Spa. Ultimately, the architects felt that joining such architectural forms together would give them a new avenue of expression that they otherwise did not have at the time. They also believed that they had stayed true to the earlier forms, so long as their designs perfectly replicated whatever it was they to mimicked.

In Europe, this approach first appeared as a rehash of Gothic Revival-style known as “Collegiate Gothic.” The European architects then used such a mentality to influence the unfolding philosophies of both the Beaux-Arts school of design, as well as the emerging Renaissance Revival-style. Many architects in America followed suit, the most notable of which being Richard Morris Hunt and Charles Follen McKim. The American architects who embraced “eclecticism” were at first interested in the country’s colonial architecture. Much of the desire to return to the time period was born from the revived interest in American culture brought on by the Centennial Exposition of 1876. Pride in preserving the nation’s heritage inspired the architects to perfect the design principles of their colonial forefathers in new and intriguing ways. This interest gradually splintered into other revival styles, though, like Spanish Colonial and Tudor Revival. Some Americans even infused the approach with the popular Beaux-Arts aesthetics of France, such as Hunt and McKim. Yet, the birth of Modernism in the 1920s and 1930s eventually ended the worldwide love affair with “eclecticism,” for architects throughout the West became more enchanted with the ideas of modernity, technology, and progress.

-

Famous Historic Events +

Battle of Mobile Bay (1864): In the latter-half of the American Civil War, the City of Mobile had become the most important port to the Southern Confederacy. Despite the presence of a large Union Naval blockade, rebel blockade runners managed to slip out of port to reach markets spread across the world. The city that most of the Confederate ships reached was Havana, where its crews exchanged lumber and cotton for much needed war supplies. And after the fall of New Orleans some two years prior, Mobile was the only place where those blockade runners could return. The Lincoln administration became increasingly aware of the city’s importance to the Confederate war effort. Ulysses S. Grant—then the Commanding General of the United States Army—instructed Admiral David Farragut to lead a force to capture the city in early 1864. The admiral took all spring to prepare for the assault, gathering a flotilla of 18 warships. Among the vessels Farragut had procured for the mission were four ironclad monitors—new steel covered boats that heralded the arrival of the battleship a few decades later. He also enlisted 5,000 men under the command of Union Major General Edward R.S. Canby to act as the landing force, once his ships breached the city’s defenses. Opposing both Farragut and Cranby were a ring of three forts that protected Mobile Bay: Fort Morgan, Fort Gaines, and Fort Powell. There was also a small squadron of four ships commanded by Admiral Franklin Buchanan, which included the mighty Confederate ironclad, the USS Tennessee. A series of small coastal batteries also lined the shores of Mobile Bay, although their overall defensive impact was limited. Furthermore, the bay itself was heavily saturated with underwater mines that sailors of the day referred to as “torpedoes.” By the summer of 1864, Mobile had truly been converted into a virtual citadel.

After spending months preparing, Admiral David Farragut began his attack up Mobile Bay on August 5, 1864. The resistance from the three forts, as well as the small Confederate fleet was immediate and fierce. Cannon shells rained throughout the countryside as Farragut’s fleet crept forward toward Mobile. As the Union ships approached a narrow channel, they were beset by a series of mines that nearly spanned the width of the bay. One ship—an ironclad named the USS Tecumseh—even struck an underwater mine and sunk. His fleet wavering, Admiral Farragut strapped himself to the mast of his flagship (a sloop called the USS Hartford) and shouted, “Damn the torpedoes! Four bells. Captain Drayton, go ahead! Jouett, full speed. Traveling single file, the remaining Union vessels cleared the mines and engaged the outnumbered Confederate navy. Three of the rebel ships were knocked out in short order, only leaving the CSS Tennessee to face Farragut. While it dealt some serious damage to the Union flotilla, it was eventually battered into a motionless hulk. Admiral Franklin Buchanan and most of his command were also captured during the battle, which ended once the Tennessee’s crew surrendered. The 5,000 men of Canby’s command (led by Major General Gordon Granger on his behalf) subsequently spent the next three weeks besieging the forts near Mobile, capturing all of them by the end of the month. Even though Union forces never bothered to enter Mobile itself, the destruction of its defenses made it useless as a port. The Union victory was covered extensively in northern newspapers afterward, and played a crucial role in Abraham Lincoln’s reelection bid later that year.

Operation Ivory Soap (1944): Starting in 1944, the Grand Hotel Resort & Spa served as the base of operations of a top secret military program known as “Operation Ivory Soap.” As the U.S. military captured one Japanese-held island after the next in the latter stage of World War II, it became increasingly clear for the need to create a system of floating air supply depots and repair centers. The time it took Navy Seabees and Army engineers to create new airfields on the capture islands was taking too long. As such, American aircraft were constantly at risk of limiting their operational range throughout the central Pacific. To resolve the crisis, the Commander of the U.S. Army Air Corps—the legendary Henry “Hap” Arnold—decided to transform nearly two dozen merchant vessels into floating repair stations that would be manned by a few hundred sailors. The ships themselves were outfitted with fuel and a variety of aircraft parts, ranging from wings to radars. Arnold also decided that he would need a specialized crew to operate the ships, and received permission to establish a special training regimen from the War Department. Lieutenant Colonel Matthew Thompson subsequently received the commission to head the school from Arnold.

Given just two weeks to organize the program, Colonel Thompson began looking for a suitable location to set up camp. When he received word that the Grand Hotel was considering a temporary closure, the colonel immediately contacted its proprietor—Edward A. Roberts—to see if he would lease him the location. Roberts was enthused. Claiming it his patriotic duty, he allowed Thompson to use the resort for a single dollar. The only caveat was that the men stationed at the Grand Hotel would have to walk through the main building barefoot, so to protect its new hardwood flooring. Soon enough, Thompson had some 5,000 men trained at the resort, learning such skills like navigation, cargo handling, and aircraft repair. Yet, he also trained them as regular infantry, instructing them to receive lessons in calisthenics, drilling, and amphibious operations. Many of the servicemen trained at the resort served in future operations during the campaigns to take Guam, the Philippines, and Iwo Jima. All the while, Colonel Thompson administered the program from his desk in Room 1108 of the Grand Hotel. The space is preserved today as a suite that guests can still reserve.

-

Famous Historic Guests +

Pattie Labelle, singer and songwriter known for such songs like “If Only You Knew,” “New Attitude” and “On My Own.”

Fannie Flagg, actress best remembered for her role in Fried Green Tomatoes.

Dolly Parton, country music icon known for such singles like “Jolene,” “Coat of Many Colors,” and “9 to 5.’

Colin Powell, 65th U.S. Secretary of State (2001 – 2005)

Barbara Bush, First Lady to former U.S. President George H.W. Bush (1989 – 1993)

Margaret Thatcher, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1979 – 1990)

Jimmy Carter, 39th President of the United States (1977 – 1981)

Guest Historian Series

Read Guest Historian SeriesNobody Asked Me, But... No. 225;

Hotel History: Grand Hotel Golf Resort & Spa (1847), Point Clear, Alabama*

By Stanley Turkel, CMHS

The site on which The Grand Hotel sits today has seen two earlier hotels so named; and the area surrounding the hotel and grounds has had a long and exciting history. It begins in 1847, when a Mr. Chamberlain built a rambling, 100-foot long, two-story hotel with lumber brought down from Mobile by sailboats. There were forty guest rooms and a shaded front gallery with outside stairs at each end. The dining room was located in an adjacent structure, and a third two-story building, called The Texas, housed the bar. Destroyed in an 1893 hurricane, the bar was rebuilt and, according to one contemporary report, "It was the gathering place for the merchants of the South, and poker games with high stakes, and billiards enlivened with the best of liquors were their pastimes." A fourth building, a two-story frame mansion called Gunnison House, was originally a private summer residence. It became a popular meeting place before the Civil War.

As one of the remaining Confederate strongholds during the Civil War, the port in Mobile was a popular spot for blockade runners. During the 1864 battle between the Confederates and Union, led by Admiral Farragut ̶ in which he famously proclaimed "damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead" ̶ the confederates bombarded the Union soldiers with torpedoes, eventually sinking the Tecumseh. A large hole was found in the wall of the Gunnison House, located on the site of the Convention Center today. The city of Mobile remained in Confederate hands until 1865 while the hotel was turned into a base hospital for Confederate soldiers.

Three hundred Confederate soldiers died while at the hospital and are buried in the on-site cemetery, Confederate Rest. The soldiers were buried shoulder-to-shoulder, in mass graves. In 1869, a fire destroyed the documents that identified the deceased and a monument to the unknown soldiers was later constructed at the cemetery, which still stands today.

The hotel reopened after the war, but was almost destroyed by a fire in 1869. Miraculously, none of the 150 guests was injured, and all their personal effects, as well as the hotel linens and most of the furniture, were saved.

Repairs were made and the hotel was soon again enjoying a prosperous existence. But then, in August 1871, tragedy struck. The twenty-seven-ton steamer Ocean Wave exploded at the Point Clear pier and scores of hotel guests died. For years afterward, sections of the wrecked steamer could be spotted during low tide.

After the explosion, Captain H. C. Baldwin of Mobile acquired the destination, and built a new hotel that resembled the earlier 100-foot-long structure, but was three times longer. Baldwin's son-in-law, George Johnson, Louisiana State Treasurer, took an active role in the business and assumed charge upon Baldwin's death. This two-story facility of sixty suites was opened in 1875. Steamers stopped at Point Clear three times a week bringing hotel guests. By 1889, boats arrived daily with the winter rates were two dollars a day, ten dollars weekly, and forty dollars by the month. The resort flourished.

In the 1890s, Point Clear was the center of the most brilliant social life in the Deep South. Boats crowded with pleasure-seekers from Mobile and New Orleans docked at the pier, carriages and tandem bikes dashed in and out of the drive; blaring bands and picnickers flocked to the broad lawns. The Grand Hotel was known as "The Queen of Southern Resorts."

By 1939, however, the place was so badly rundown that its new owners, the Waterman Steamship Company, had it razed and, in 1940, built Grand Hotel III. This was a modern air-conditioned building with ninety rooms; it spread long and low, with giant picture windows and glassed-in porches. A few years later, cottages were constructed, utilizing lumber, especially the fine heart-pine flooring and framing, from the old building. During World War II, when the shipping company turned over the facilities to the United States government for $1 million, it was with the stipulation that the soldiers were not to wear shoes indoors lest they damage the pine floors.

In 1955, the hotel was acquired by McLean Industries, and ten years later J. K. McLean himself brought it and formed the present Grand Hotel Company. A new fifty-room addition was built, and extensive improvements were made.

In 1967, a second 9-hole golf course and the first conference center were added. In 1979, the hotel closed as a result of Hurricane Frederick. The hotel reopened on April 10, 1980. In 1981, the Marriott Corporation bought The Grand Hotel and added the North Bay House and the Marina Building, bringing total guest rooms to 306. In 1986, the old Gunnison House was torn down to make way for The Grand Ballroom. Marriott added an additional 9-hole golf course for a total of 36 holes. Major renovations to the hotel were completed in 2003, including a new spa, pool and additional guest rooms. Renovation of the Dogwood course was completed in 2004. The renovation of the Azalea course was completed in 2005.

An expansion of the Grand's grounds and new real estate opportunities were announced in 2006. The Colony Club at the Grand Hotel opened in spring 2008 and featured condominiums overlooking picturesque Point Clear and Mobile Bay. A new aquatics facility and a tennis center opened at the resort in July 2009.

Daily patriotic military salute and cannon firing started in 2008 as the hotel continues to honor the military influence. Each day a processional begins at the lobby, weaves around the grounds, and concludes with the firing of a cannon at 4:00 p.m.

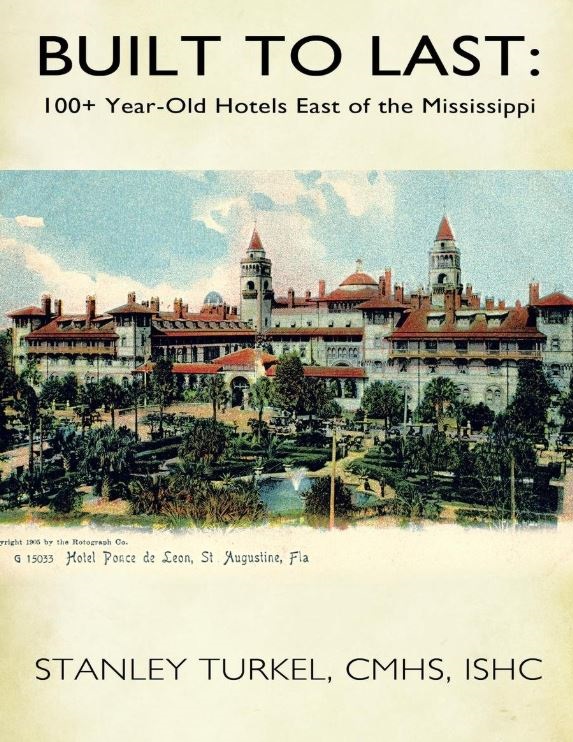

*excerpted from his book Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels East of the Mississippi

*****

About Stanley Turkel, CMHS

Stanley Turkel is a recognized consultant in the hotel industry. He operates his hotel consulting practice serving as an expert witness in hotel-related cases and providing asset management an and hotel franchising consultation. Prior to forming his hotel consulting firm, Turkel was the Product Line Manager for worldwide Hotel/Motel Operations at the International Telephone & Telegraph Co. overseeing the Sheraton Corporation of America. Before joining IT&T, he was the Resident Manager of the Americana Hotel (1842 Rooms), General Manager of the Drake Hotel (680 Rooms) and General Manager of the Summit Hotel (762 Rooms), all in New York City. He serves as a Friend of the Tisch Center and lectures at the NYU Tisch Center for Hospitality and Tourism. He is certified as a Master Hotel Supplier Emeritus by the Educational Institute of the American Hotel and Lodging Association. He served for eleven years as Chairman of the Board of the Trustees of the City Club of New York and is now the Honorary Chairman.

Stanley Turkel is one of the most widely-published authors in the hospitality field. More than 275 articles on various hotel subjects have been posted in hotel magazines and on the Hotel-Online, Blue MauMau, Hotel News Resource and eTurboNews websites. Two of his hotel books have been promoted, distributed and sold by the American Hotel & Lodging Educational Institute (Great American Hoteliers: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry and Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels East of the Mississippi). A third hotel book (Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels in New York) was called "passionate and informative" by the New York Times. Executive Vice President of Historic Hotels of America, Lawrence Horwitz, has even praised one book, Great American Hoteliers Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry:

- “If you have ever been in a hotel, as a guest, attended a conference, enjoyed a romantic dinner, celebrated a special occasion, or worked as a hotelier in the front or back of the house, Great American Hoteliers, Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry is a must read book. This book is recommended for any business person, entrepreneur, student, or aspiring hotelier. This book is an excellent history book with insights into seventeen of the great innovators and visionaries of the hotel industry and their inspirational stories.”

Turkel was designated as the “2014 Historian of the Year by Historic Hotels of America,” the official program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. This award is presented to an individual for making a unique contribution in the research and presentation of history and whose work has encouraged a wide discussion, greater understanding and enthusiasm for American History.

Works published by Stanley Turkel include:

- Heroes of the American Reconstruction (2005)

- Great American Hoteliers: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2009)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels in New York (2011)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels East of the Mississippi (2013)

- Hotel Mavens: Lucius M. Boomer, George C. Boldt and Oscar of the Waldorf (2014)

- Great American Hoteliers Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2016)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels West of the Mississippi (2017)

- Hotel Mavens Volume 2: Henry Morrison Flagler, Henry Bradley Plant, Carl Graham Fisher (2018)

- Great American Hotel Architects Volume 1 (2019)

- Hotel Mavens Volume 3: Bob and Larry Tisch, Curt Strand, Ralph Hitz, Cesar Ritz, Raymond Orteig (2020)

Most of these books can be ordered from AuthorHouse—(except Heroes of the American Reconstruction, which can be ordered from McFarland)—by visiting www.stanleyturkel.com, or by clicking on the book’s title.