Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

Discover the Hotel Indigo St. Louis - Downtown, which was once a gorgeous business complex known as the La Salle Building.

Hotel Indigo St. Louis - Downtown, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2022, dates back to 1909.

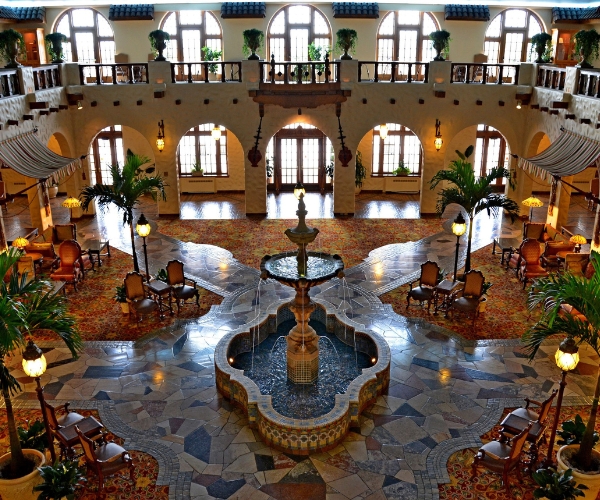

VIEW TIMELINEListed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places, the Hotel Indigo St. Louis Downtown stands today as a brilliant historic hotel. Indeed, the destination is renowned in St. Louis for its fantastic services and luxurious amenities. But this fascinating location has not always been a historic hotel. On the contrary, the Hotel Indigo St. Louis Downtown was originally constructed to serve as a magnificent office complex around the start of the 20th century. Renowned architect Isaac S. Taylor specifically spearheaded the project in 1908, who had just finished creating numerous designs for the celebrated St. Louis World’s Fair a few years prior. Taylor proceeded to design a gorgeous 13-story structure that loomed over the intersection of Broadway and Olive Street in the heart of the city. He specifically crafted a gorgeous red-brick façade set upon a concrete foundation made using the intricate Simplex method. (Concrete was essentially poured into the soil via a tube bored into the ground.) The bay windows featured a wealth of their own ornate details, too, including cast-iron cornices and carved-wood moldings. Perhaps the most stunning component was Taylor’s use of white-glazed terra cotta, particularly on the building’s first two exterior levels. Inside, Taylor instituted similar extravagant work, such as the installation of marble-lined walls, multi-colored ceramic tiles, and several brass-inlaid elevators.

When construction finally concluded a year later, Taylor’s stunning office building immediately amazed all who stepped inside. Dozens of corporate tenants quickly rented space within the structure, turning it into one of the busiest commercial complexes in downtown St. Louis. To formally inaugurate the edifice, its proprietors subsequently decided to grant it a memorable name. They settled on calling it the “La Salle Building” after René-Robert Cavelier, who was the European aristocrat who first explored the region. The building remained a fixture in St. Louis for many generations thereafter. Unfortunately, subsequent owners initiated their own renovations that gradually diminished its grand historic architecture. By the middle of the century, many locals lamented how much it had changed in an effort to make it appear “modern.” Thankfully, salvation arrived during the 1980s, when The Korte Company acquired the site and initiated a massive restoration to restore much of its historic appearance. The trend continued a few decades later once ViaNova Development obtained the building in 2016. Partnering with IHG Hotels & Resorts, ViaNova Development revitalized even more of the structure’s historical components amid efforts to transform it into a wonderful boutique hotel called the “Hotel Indigo St. Louis - Downtown.” Now open since 2021, the future of this magnificent historical landmark has never looked brighter.

-

About the Location +

Long ago, the site of present-day St. Louis was once inhabited by Native Americans of the ancient Mississippian culture. Due to the area’s proximity to both the Mississippi and Missouri rivers, thousands of indigenous people frequented the location for generations. The locale held spiritual significance among the Mississippians, who constructed dozens of earthen mounds as religious monuments. Known as the Cahokia Mounds, the earthworks were one of the most enduring geological features in the region. Indeed, the formations even gave St. Louis the moniker of “Mound City” during its formative years. (Unfortunately, most were destroyed throughout the 19th century as St. Louis expanded in size. Only a small segment survives as the Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site.) Nevertheless, St. Louis itself first came into existence when two French fur trappers—Pierre Laclede Liguest and his stepson, Auguste Chouteau—opened a trading post in 1764. While the area was no longer under French control, Liguest proceeded to develop his small community via a land grant given to him earlier by King Louis XV of France. He subsequently began creating the village a year later, naming it after another French monarch, King Louis IX. Over time, settlers from Canada and France began to arrive in St. Louis, who were attracted by its vibrant local fur trading industry.

St. Louis and the surrounding countryside only returned to France during the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte in the late 18th century. (It had originally lost it to Spain in the wake of the Seven Years’ War.) But St. Louis then became a part of the nascent United States after Bonaparte sold the surrounding area to the Jefferson administration via the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. It immediately assumed great strategic importance to President Thomas Jefferson, who used it as the final launching point for the historic Lewis and Clark Expedition. St. Louis remained a gateway into the American West for many years thereafter, attracting scores of migrants from across the country over the following decades. Their numbers were supplemented by thousands of European immigrants, specifically Irish and German settlers who wished to create their own communities out on the frontier. Even though a majority of the settlers merely used St. Louis as a springboard to go further west, quite a few stayed in town and made it their home. As such, St. Louis underwent unprecedented growth as its population swelled in size. In fact, the settlement had rapidly transformed into a city mere decades after the American Revolution. St. Louis continued to expand throughout the rest of the 19th century, with its residents voting to establish a home-rule charter during the Gilded Age.

The city continued to be a nexus for travel toward the Pacific coast in the early 20th century, although its status as middle America’s preeminent transportation hub had been supplanted by Chicago. However, St. Louis continued to prosper, thanks to the emergence of largescale industrialization. Perhaps the greatest symbol of St. Louis’s economic success was the renowned Eads Bridge, which helped ship countless manufactured goods all over the nation. Its rising prestige even got it to host two major international events in 1904--the St. Louis World’s Fair and the Summer Olympics! But the city’s prosperity came to an end unfortunately, as it entered a period of decline after World War II. Undeterred, a coalition of local civic leaders and businesspeople sought to reverse St. Louis’ stagnation. Beginning in the 1960s, those concerned citizens launched dozens of construction projects that revitalized downtown St. Louis. Some of the greatest plans led to the creation of well-known landmarks like the ceremonial Gateway Arch and Busch Memorial Stadium, home to the city’s iconic St. Louis Cardinals. The redevelopment efforts worked brilliantly, which resurrected St. Louis’ identity as one of America’s leading cities by the century’s end. St. Louis is still an influential metropolis that now attracts cultural heritage travelers from across the world year after year.

-

About the Architecture +

Despite its location in St. Louis, the Hotel Indigo St. Louis - Downtown stands today as a brilliant example of Chicago Commercial-style architecture. Commonly known as “Chicago School,” this unique architectural form first emerged in America’s Windy City at the height of the Gilded Age before spreading elsewhere in America. While no actual “school” existed in Chicago that taught the aesthetic, historians today agree that a common set of design principles unified the city’s architects around the turn of the 20th century. Among the most well-known features of Chicago Commercial-style buildings involved the use of steel frames clad in masonry (usually terra cotta). The reliance upon steel and durable masonry came about following the aftermath of the Chicago Fire of 1871, when most of the city’s preexisting structures were destroyed in the calamity. The building materials also allowed architects to install many large plate-glass windows throughout the façade. Called the “Chicago window,” the fixtures consisting of three-parts centered along a panel that was flanked by two smaller sash windows. The arrangement resembled a grid, in which some spaces projected out from the exterior and formed bay windows.

Nevertheless, the architects within the Chicago Commercial-style school of thought believed that their buildings should reflect the prosperity and technological progress of the Industrial Revolution. As such, the structures borrowed several powerful aspects of Neoclassical architecture. Chicago Commercial-style skyscrapers were typically divided into the three distinctive sections that have historically formed what is known as the “classical column.” The lowest parts of the building acted as the base, where the most ornate architectural elements appeared. Much of the detailing occurred around the entryways, as well as any nearby windows. The middle floors of the structure often featured far less detail, which functioned as the “shaft” of the column. The grand ornamentation returned toward the final two stories, though, creating what architects called the “capital.” The “capital” was typically defined by its flat roof and brilliant cornice, as well. Many buildings across Chicago brilliantly encapsulated this architectural approach, such as the Reliance Building, the Chicago Building, and the Rookery Building. The style’s popularity rapidly appeared in other cities, too, including a rapidly industrializing St. Louis.