Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

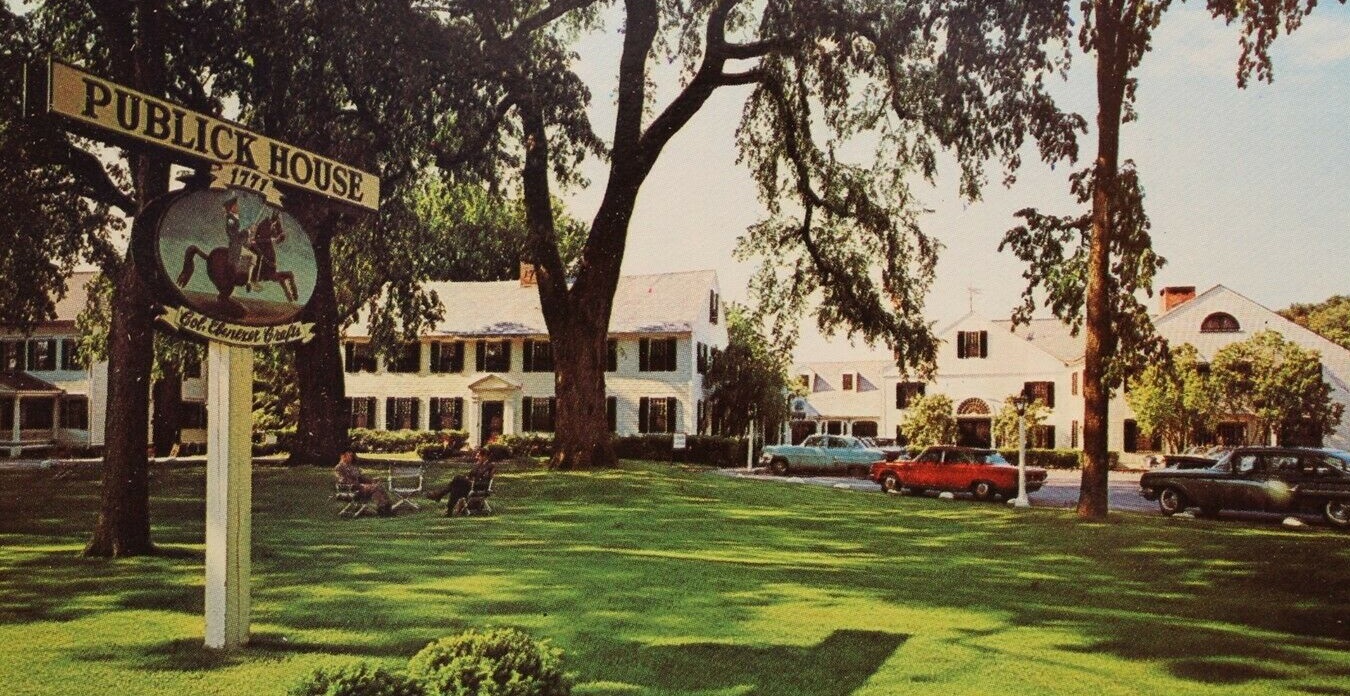

Discover the Publick House Historic Inn with its history dating to before the American Revolution.

Publick House Historic Inn, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2018, dates back to 1771.

VIEW TIMELINEA member of Historic Hotels of America since 2018, the Publick House Historic Inn was originally established on the eve of the American Revolution. Colonel Ebenezer Crafts specifically constructed the inn during the late 18th century, who had originally planned to go into the ministry after his time at the Yale Divinity School. Upon the suggestion of his college friend, Joshua Payne, Crafts applied to a parish in Sturbridge, Massachusetts. Payne was chosen over him, though, and friendship subsequently splintered. Crafts went back to Pomfret, Connecticut, where he married and began a life in the military as an homage to his father. But following the loss of two children, Crafts' wife, Mehitabel, asked Crafts to leave Pomfret for a new beginning. Payne reached out and offered Crafts the chance to return to Sturbridge as a means of rekindling their friendship. While visiting, Crafts fell in love with a plot of land that flanked the town green. Learning that it belonged to a local resident named Dr. Elisha Marcy, Crafts sought to acquire the parcel for himself. Dr. Marcy nevertheless refused Crafts’ constant overtures to sell the property. Undeterred, Crafts ultimately challenged the doctor to a game of “cards,” with Marcy’s landholdings used for collateral.

The colonel managed to win the bet and immediately moved his family north to Sturbridge. With help provided by Payne and his parishioners, Crafts began to construct a massive home on the lot. But Crafts’ designed his new residence to serve as more than just a home. On the contrary, Crafts had actually converted a portion of the structure to function as roadside inn. His new building stood two stories in height and was set atop a foundation based on a central hallway. The building’s ground floor featured several public rooms and a large kitchen, while 13 guestrooms resided upstairs for overnight guests. Some of the rooms on the first floor provided specific services to Crafts’ guests, too. There was a general store in what is now the Pumpkin Room; a men’s smoking room (now the Card Room) for daily gatherings, news sharing, and gossip; and a Ladies Parlor connected right next door. The kitchen, which is now the Tap Room, held a huge fireplace for cooking large batches of food in what is now a hearth. The Tap Room—currently the Pineapple Room—held large barrels of rum, from which the robust Crafts would lift and drink from directly.

When Crafts finally debuted his wonderful new inn during the 1770s, he decided to call it “Crafts Tavern.” But Crafts also referred to the structure as the “Publick House” in recognition of the inn’s mission to service the people of Sturbridge. The inn nonetheless saw its business decline after a depression struck the young United States in the wake of the American Revolutionary War. Due to the financial constraints, Crafts was forced to sell his beloved inn and moved to Vermont, where he founded the town of Craftsbury. Now known only as the “Publick House,” the inn survived the depression to reemerged as a popular landmark in downtown Sturbridge. In fact, the building hosted both the Marquis de Lafayette and his son, Georges Washington de Lafayette, when the two famously toured the nation during the 1820s. But the proliferation of the railroads throughout Massachusetts some three decades later eventually spelt doom for the Publick House, as they diverted the inn’s steady stream of clients to town’s located elsewhere.

By the beginning of the 20th century, the Publick House was unfortunately a shadow of its former self. The inn was even transformed into a boarding house for women called “The Elms” for a brief time, although it nearly closed down due to its dilapidated state. Fortunately, salvation arrived in the form of Richard Paige, who bought the entire complex for a single dollar amid a card game. Working alongside architect James A. Britten, Paige carefully restored the building back to its roots, which thus gave it a completely new lease on life. Thanks to his innovation and respect for history the Publick House Historic Inn has never closed its doors since. As such, this fantastic historic hotel has continued to offer unmatched hospitality and affordable accommodations to guests well into the present.

-

About the Location +

In 1644, a group of English Puritans led by John Winthrop the Younger settled the area, attracted by tales that the land yielded rare minerals like graphite, lead, and iron. At the time of their arrival, the locale was known only by the Native American name of “Tantiousques.” Winthrop managed to purchase the region from the natives and immediately set about creating a mine that would access the rocks and metals beneath the bedrock. The mine proved fruitful enough for Winthrop and his descendants, for it remained in their family until the 1780s. In fact, the mine itself stayed open generations thereafter, evenutally closing for good at the start of the 20th century. But despite the mine’s relative successes, the area remained sparsely inhabited for years. The first actual community to appear in the vicinity materialized in 1729, after a few English colonists from nearby Medfield created a rudimentary village close to the Quinebaug River. The residents continued to petition the Massachusetts General Court for incorporation, but failed numerous times due to the court’s belief the ground was too arid to support a community. Nevertheless, the settlers eventually succeeded in convincing the colonial authorities to grant a charter, resulting in the official birth of Sturbridge in 1738.

Sturbridge nonetheless continued to operate as small, bucolic town, despite the presence of two major roadways that bisected it (today’s Routes 20 and 31). Sturbridge numbered just a few homes huddled around a quaint green, which the prominent Saltonstalls family had created on behalf of the town shortly before the start of the American Revolution. Sturbridge’s growth into a recognizable New England community did not truly begin until the opening of the Publick House Historic Inn, which served as the catalyst for a vibrant domestic market. Save for a brief depression that transpired after the war, business in Sturbridge multiplied tenfold from increased foot traffic along the local thoroughfares. Soon enough, the Publick House was joined by many other storefronts, including blacksmiths, tailors, mechanics, and even a doctor’s office. So much economic activity had occurred that the entire area surrounding the green was fully developed by the start of the early 19th century. Most of the new buildings reflected the reigning architectural influences of the day, too, including Georgian, Federalist, and even Greek Revival-style design aesthetics. As such, downtown Sturbridge became on of the most picturesque communities in all of western Massachusetts.

Over time, the prosperity extended out into Sturbridge’s outlying villages, especially once local entrepreneurs opened mills in places like Fiskdale and Westville during the 1820s and 1830s. But the coming of the railroads two decades later saw Sturbridge’s economic prospects decline considerably, as regional merchants began to avoid using the roads in favor of steam locomotives. Sturbridge reverted back to being a rustic country hamlet, with much of its community remaining frozen in time. The town nonetheless saw a return to relevance a century later when the Wells family transformed a nearby farmstead into a living history village dedicated to preserving New England’s historic rural life. Debuting as “Old Sturbridge Village” in 1946, the community is now a brilliantly preserved collection of 59 unique historical structures dating back to America’s formative years. It has since become one of the nation’s most attractive historic sites, alluring thousands of interested guests year after year. Contemporary cultural heritage travelers flock to downtown Sturbridge in great numbers, too, for many of its historic buildings are listed as part of the federally recognized “Sturbridge Common Historic District.” Few places in New England can truly rival the historical magnificence that still defines Sturbridge today.

-

About the Architecture +

The Publick House Historic Inn stands as a brilliant example of American colonial architecture. Architectural historians today generally define American colonial architecture as covering a wide berth, subdividing it into categories like First Period English, French Colonial, Spanish Colonial, and Dutch Colonial. But most professionals in the field believe that the aesthetics embraced by English—and later British—colonists to be the most ubiquitous, given their widespread cultural influence during America’s infancy. It dominated the architectural tastes of most Americans at the time, until the Federalist design principles overtook them in the 19th century. The style was especially predominant in New England, which quickly saw the creation of another set of two unique subtypes—Saltbox and Cape Cod-style. A different take of English colonial architecture appeared within the southern colonies, as well, which some experts refer to as “Southern Colonial.” The building style resembled the general trends embraced by other colonists in British America, although they differed in that they constructed a central passageway, massive chimneys, and a parlor. Nevertheless, all of the buildings shared strikingly similar qualities. American homes of the age were uniformly simple, and made use of either wood, brick, or stone. Rectangular in shape, they typically extended two to three stories in height. All of the formal parts of the home were located on the first floor, while the family bedrooms occupied the upper levels of the building. The floorplans were also fairly limited in scope, designed to fill each level with just a couple of rooms. This simplicity was slowly modified by the arrival of Georgian-style architecture from Great Britain toward the end of the 18th century. Architects subsequently relied more upon mathematical ratios to achieve symmetry in their designs, and used elements of classical architecture for ornamentation.

-

Famous Historic Guests +

Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, French General who was a hero of the American Revolution.

Georges Washington Louis Gilbert de La Fayette, son of the Marquis de Lafayette.