Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

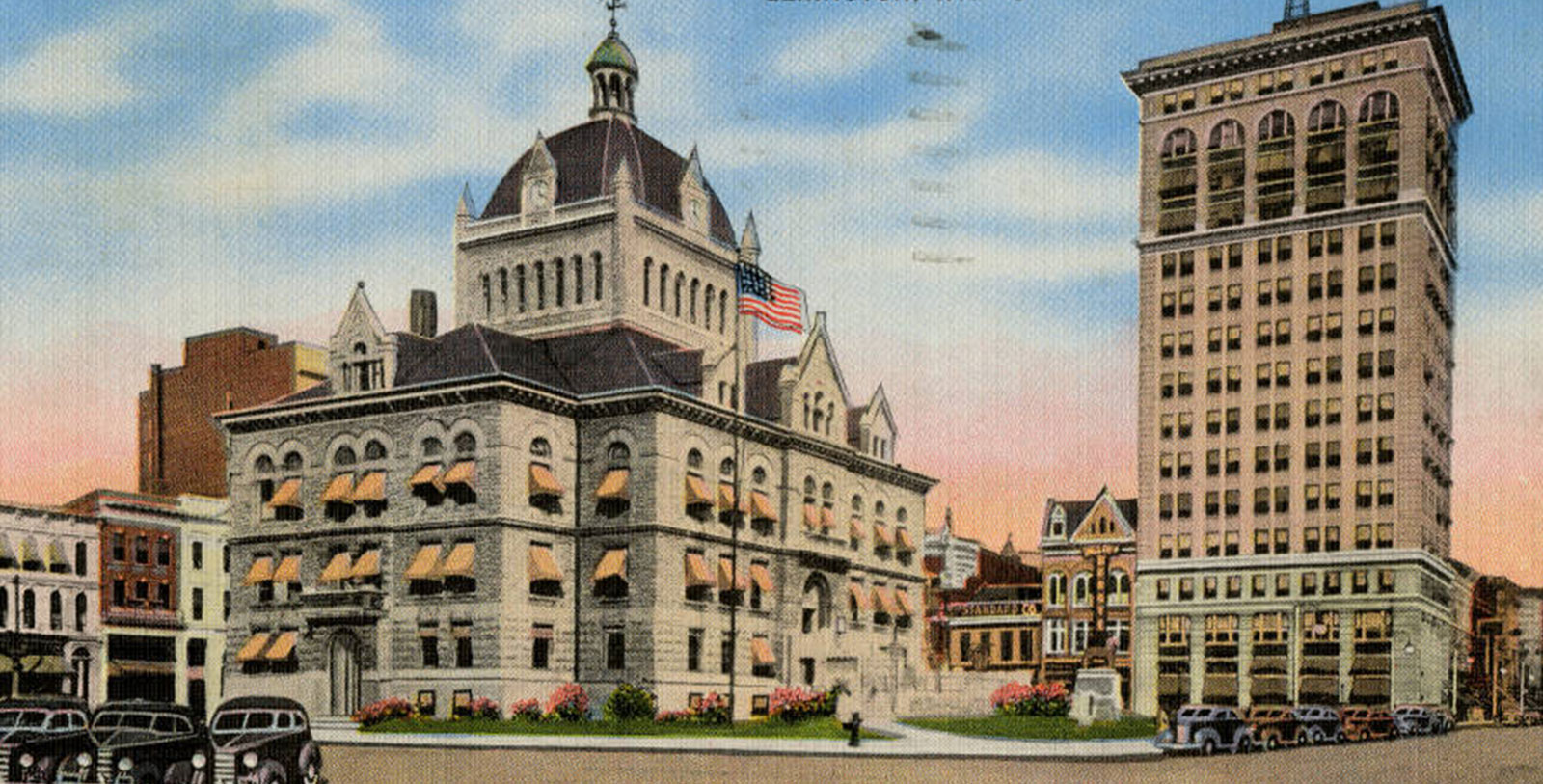

Discover the 21c Museum Hotel Lexington by MGallery, which was once the headquarters of the Fayette National Bank in downtown Lexington.

21c Museum Hotel Lexington by MGallery, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2019, dates back to 1914.

VIEW TIMELINEThe origin of the historic 21c Museum Hotel Lexington by MGallery dates back to the early 1900s, when the preeminent Fayette National Bank constructed a grand headquarters in downtown Lexington. Founded in 1870, the Fayette National Bank had emerged as a dominant financial institution in central Kentucky by the beginning of the twentieth century. Yearning for a place to do business that could properly reflect its prestigious reputation, the company decided to demolish its original bank for a more modern one. The Fayette National Bank subsequently hired the illustrious, New York-based architectural firm McKim, Mead & White to oversee its ambitious construction project. Highly-regarded for its distinguished portfolio, McKim, Mead & White would soon add another feather to its cap when it began designing the new Fayette National Bank Building. Using a stunning array of Beaux-Arts Classical, Imperial Roman, French Renaissance, and Baroque design elements, the skyscraper was an architectural masterpiece upon its completion in 1914. The Fayette National Bank operated out of the towering edifice for the next several decades, even after the company was consolidated into the First National Bank amid the Great Depression. By the century’s end, the building had ceased operating as a bank. But thanks to the concern of Laura Lee Brown and Steve Wilson—the visionary founders of 21c Museum Hotels—the structure became alive once more. Recognizing its inherent beauty and historical significance, Brown and Wilson transformed the erstwhile bank into a boutique hotel in 2012. Debuting four years later as the “21c Museum Hotel Lexington,” the venue quickly became renowned for its unique guest experience. Despite its formal role as a hotel, the building also functions as a contemporary art gallery that immerses its visitors with thought-provoking, innovative artwork. Now listed on the National Register for Historic Places, Brown and Wilson have been honored to share this amazing place with travelers from around the world. Due to their tireless commitment, they successfully recast the building as both a glorious holiday destination, as well as a respected local cultural center. The 21c Museum Hotel Lexington has been a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2019.

-

About the Location +

In 1775, a group of settlers led by William McConnell established a rudimentary camp near the site of Elkhorn Creek. Now known as “McConnell Springs,” the community was one of the first permanent settlements to appear west of the Appalachian Mountains. McConnell’s camp at the time was actually a part of the Colony of Virginia, inhabiting a massive space of territory known as “Kentucky County.” (Colonial officials in Virginia believed that their territory stretched all the way to the Mississippi River.) The village itself was incredibly small, featuring just a single stockade within which McConnell and his fellow frontiersmen resided. But when word reached the settlers of their countrymen’s victory at the Battle of Lexington and Concord a few months later, they quickly christened their nascent community as the town of “Lexington.” Its residents retained the name Lexington when the Virginia General Assembly officially chartered it as a town in 1782. Lexington soon became the most important town in the Trans-Appalachian West, with many new economic, religious, and educational institutions debuting in the years that followed the American Revolution. It specifically served as the home to Transylvania University and the Christ Church Episcopal. The First African Baptist Church also debuted around the same time, becoming the third-most historic black congregation in the whole United States. Lexington even briefly functioned as the capital for the newly formed Commonwealth of Kentucky in 1792, although it eventually lost that status to Frankfort a year later. By the dawn of the 19th century, many had thus taken to calling the city, the “Athens of the West.”

Despite the loss of its political importance, Lexington continued to be a significant center of commerce and culture during the 1800s. Agriculture arose as the dominant trade, with the cultivation of hemp its most lucrative crop. Merchants and industrialists soon opened their own respective businesses in the heart of Lexington that specialized in the sale of the plant, as well as its transformation into rope. The most prosperous agriculturalists were planters who owned large plantations out in the surrounding countryside. As Kentucky was then a slave state, those estates were populated by thousands of slaves brought west from ports near the Atlantic. (The enslaved African Americans eventually formed a vibrant community of their own in the aftermath of the American Civil War.) One entrepreneur, John Wesley Hunt, was so successful in the sale of rope that he became the first millionaire west of the Appalachian Mountains. Horse breeding also emerged as a popular industry in Lexington, with some locals even racing their prized thoroughbreds on the outskirts of the city. This practice eventually gave rise to the creation of the American Thoroughbred Breeders Association and the Keeneland Racecourse (its first competition was held in 1875.) Over time, other industries debuted in Lexington, such as the manufacture of whiskey, literature, and machinery. As such, Lexington was one of the most affluent market towns in both Kentucky.

Many famous Americans also called Lexington home in the 19th century. One of the most well-known families to reside within the city limits were the Todds, living in a dwelling along West Main Street. Their most famous member was Mary Todd, who eventually married Abraham Lincoln in 1842. She would, thus, become First Lady of the United States when her husband became the 16th President of the United States in 1860. Another famous resident at the time was the great U.S. Senator Henry Clay. Clay specifically lived in a mansion called “Ashland” on Mill Street whenever he was not in the nation’s capital to conduct business. And he was in Washington a lot during his life. Starting his national political career as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, Clay made a name for himself as the “Great Compromiser” for his role in making deals between the North and South as a Senator. Some of his greatest legislative achievements included the Missouri Compromise and the Compromise of 1850. He also served as the Secretary of State in the presidential administration of John Quincy Adams and even came close to winning the office for himself on five separate occasions. And as one of the founders of the short-lived Whig Party (a predecessor to today’s Republican Party), he believed in melding public and private interests together to fuel the national economy via his “American System.” Other principles that Clay held involved the respect of Native American rights and peace with Mexico. Today, historians often hail Clay as part of the “Great Triumvirate,” a position he shared with fellow antebellum senators, Daniel Webster and John C. Calhoun.

-

About the Architecture +

Renowned architectural firm McKim, Mead & White oversaw the original design of the 21c Museum Hotel Lexington by MGallery when it was the Fayette National Bank Building. The company was quite accomplished by the time it started work on the structure, having crafted the appearance of such landmarks like Pennsylvania Station, the first Madison Square Garden, and the main campus of Columbia University. According to the U.S. Department of the Interior, the principal building materials used were stone and buff brick that featured a glazed tile trim. But to create the base, the firm relied upon some beautiful Bedford limestone and pink granite. The main entrance had two pairs of Ionic columns, while square piers resided off on the sides of the building. A huge and elaborate cornice sat near the roofline, designed with modillions in a “Florentine” manner, complete with lion’s-head blocks. Fenestration existed on the bottom three floors, with narrower sections on both sides of the central windowpanes. (The details for the mezzanine level were not clearly visible, as a transom took its place.) Fine tiling also appeared along the third, fourth, and twelfth floors, containing meander and egg-and-dart moldings. Furthermore, in the words of the agency:

- “The design of this building makes it one of their more handsome "skyscrapers," suggesting a Renaissance merchant prince's palazzo at vast scale, with its colossal three-story orders at top and bottom; the handsome but restrained classical details accentuating horizontal divisions that make the elevations as a whole conform to the base, shaft, and capital of a column; and the climactic projecting cornice. The structure is the last and finest of the group of high-rise towers most designed lay non-Lexington architects for banks, no doubt in competition with each other that punctuate the corners of the courthouse square. It continues to provide attractive and functional office space and contributes considerable distinction to the city's architectural heritage and its urban skyline.”

And while the 21c Museum Hotel Lexington showcases many unique design elements, the most prominent architectural style to appear in its design is that of the Beaux Arts. Beaux-Arts-style architecture itself became widely popular around the dawn of the 20th century. This beautiful architectural form originally began at an art school in Paris known as the École des Beaux-Arts during the 1830s. There was much resistance to the Neoclassism of the day among French artists, who yearned for the intellectual freedom to pursue less rigid design aesthetics. Four instructors in particular were responsible for establishing the movement: Joseph-Louis Duc, Félix Duban, Henri Labrouste, and Léon Vaudoyer. The training that these instructors created involved fusing architectural elements from several earlier styles, including Imperial Roman, Italian Renaissance, ad Baroque. As such, a typical building created with Beaux-Arts-inspired designs would feature a rusticated first story, followed by several more simplistic ones. A flat roof would then top the structure. Symmetry became the defining character, with every building’s layout featuring such elements like balustrades, pilasters, and cartouches. Sculptures and other carvings were commonplace throughout the design, too. Beaux-Arts only found a receptive audience in France and the United States though, as most other architects at the time gravitated toward British design principles. American architects in particular made great use of the style, especially the founding members of McKim, Mead & White—Charles Follen McKim, William Rutherford Mead, and Stanford White.

-

Art Collection +

Specially commissioned site-specific works by some of the contemporary art world's most exciting artists can be found throughout 21c Museum Hotel Lexington. Roaming throughout the building, in the restaurant, galleries, and guestroom floors, 21c Lexington’s Blue Penguin by Cracking Art Group can be found around every corner. These four-foot-tall sculptures made of recycled plastic, move around the building each day and serve as a playful reminder of the importance of sustainability and environmental conservation. Inspired by the ordered asymmetry of crystals, New York design studio SOFTLab has also transformed the entry of the 1914 Fayette National Bank into an immersive installation that looks different from every angle. By cladding the complex aluminum structure with 3M dichroic acrylic, the piece changes color and reflectivity as visitors move around it. Lit from within by LEDs, the large crystalline structures cast colored light onto the surrounding space, using it as a canvas. The installation acts as both a spectacular form and a giant lantern, creating a landscape of color, an otherworldly atmosphere.

Varying in color and lit from within, the acrylic spheres hanging overhead in Lockbox, the restaurant at 21c Lexington, are arranged as atmospheric molecules in Bigert & Bergstrom’s multi-media installation, Tomorrow’s Weather. The atmospheric molecules (H2O, C2, N2, etc.) change color depending on the following day’s weather forecast. The work updates three times a day in accordance with the latest weather service reports, changing its guise accordingly. If sunny skies are predicted, the molecules take on blue tones with splashes of yellow; if clouds and rain are approaching, the molecules reflect a variety of grey tones. The lone single globe moving up and down responds to temperature: on cold days it hangs low and glows blue, while a warm front makes the globe rise and turn red. Form and function converge in this work that is both an informative instrument—viewers can potentially learn tomorrow’s predicted weather—and an abstract arrangement of light and color whose shifts may be as unreliable as the forecast controlling their dynamic fluctuations.

In Lockbox’s private dining room, formally the Fayette National Bank’s vault, Lyons and Wilson’s contemporary ceramic tile installations reference aspects of cultural antiquity while addressing current social, economic, and political issues. Featuring images of bullet casings, BRASS is one of several works in the Unswept Floors series, an investigation of current material culture reflecting back on an ancient Roman home decorating trend of commissioning mosaics of images of fallen food scraps from extravagant dinner parties. This practice began with the importation of exotic foods, continued with the means to serve them to a large number of guests, and then moved further on with the commissioning of artwork depicting the detritus of these feasts. The Greek artist Heraclitus is credited with the 2nd century BC “Unswept Floor” mosaic at the Vatican Museums that was recovered from a villa on the Aventine Hill outside Rome. And, in direct homage, various foods create floor, wall, and ceiling porcelain tile installations, utilizing the modern process of sublimation (a combination of heat and pressure) to embed photographic images into tile.

Visitors, tourists, and the public, as well as hotel and restaurant guests, are greeted outside of the building by Totally in Love, two intertwined lampposts, their supple, arched lines and blown glass bulbs transforming industrial urban design into playful, organic form. Dutch artist Pieke Bergmans originally conceived of these lamppost lovers for an exhibition in Italy entitled Metamorphosis. This metamorphosis is an anthropomorphic one, turning streetlights into a couple Totally in Love. Bergman’s practice focuses on altering existing production processes to combine function, form, and message in a single elegant gesture.

The exterior of the building currently features two artworks. Ebony G. Patterson’s I AM A PROMISE, from the series ‘…when they grow up.” The brightly colored vinyl work pictures a young Black child, innocent and full of promise. But the artist also asks their audience to consider the ramifications of a society that does not view a person as that promise, but rather a threat. On the rear of the building, Jessica Sabogal’s mural Daughter of Immigrants, a larger-than-life, close-up view of a young child, recognizes the artist’s place as a first-generation, Colombian-American immigrant. Sabogal dedicates this work to all those who her parents, as well as for all those caught in between the pressures associated with the harrowing experience of adapting to a new life in America.