Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

historic annapolis hotels

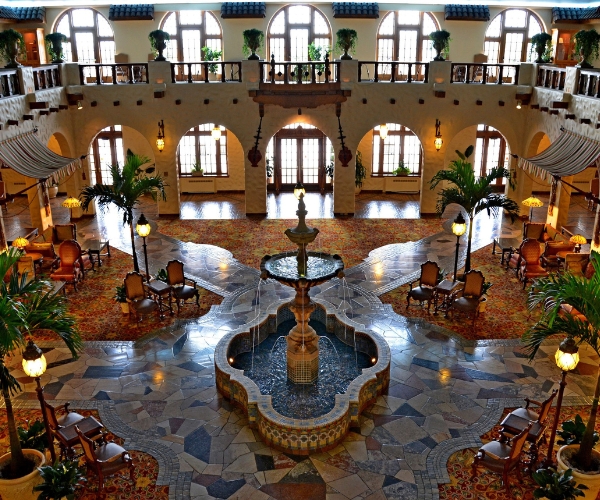

Discover Historic Inns of Annapolis, which comprise three historic buildings: Maryland Inn, Governor Calvert House and Robert Johnson House.

Historic Inns of Annapolis, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 1996, dates back to 1727.

VIEW TIMELINEMembers of Historic Hotels of America since 1996, the Historic Inns of Annapolis are some of the finest holiday destinations in all of Maryland. Since the 1700s, each building within the collection has stood as a prominent local landmark in Annapolis. The Historic Inns of Annapolis comprise three historic buildings, each with its own character. The Maryland Inn, the Governor Calvert House, and the Robert Johnson House tell a fascinating story of American history. They have all operated as popular lodgings for statesmen and dignitaries throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. Delegates to the Congress of the Confederation stayed at the inns when George Washington resigned as Commander in Chief of the Continental Army, as well as for the ratification of the Treaty of Paris. Their history has even earned them a cherished listing in the U.S. National Register of Historic Places as part of the Colonial Annapolis Historic District. Few other hotel operations in the nation can claim as great a heritage as the Historic Inns of Annapolis.

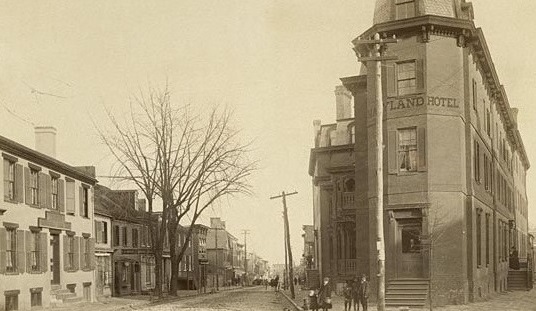

Maryland Inn:

In 1772, Thomas Hyde, a respected merchant and civic leader, acquired a long-term lease on a lot at State Circle. Hyde subsequently had the front portion of what is now the Maryland Inn constructed upon the grounds. Under his watch, the inn became a favorite destination for many illustrious guests visiting Annapolis. This was especially true in regards to the national political figures who traveled to the city to serve in the Congress of the Confederation right after American Revolutionary War (Annapolis briefly became the national capital once the war had ended). But Hyde eventually advertised it for sale. It was described as, "an elegant brick house adjoining Church Circle in a dry and healthy part of the city, this House is one hundred feet front, three story height, has 20 fireplaces and is one of the first houses in the state for a house of entertainment." Fortunately, Sarah Ball—the former manager—eventually purchased the business in 1784 and operated it to great local praise. A local newspaper even reported, “[Sally Ball] has opened a tavern at the house formerly kept by her, fronting Church (now Duke of Gloucester) Street; and having supplied herself with everything necessary and convenient, she solicits the favors of her old customers and the public in general.”

The inn remained a popular throughout the 19th century. It was acquired by the Maryland Hotel Company in 1868 and remained the most prominent of Annapolis’ many hotels. The Maryland Inn even continued to function as the favorite rendezvous for important guests of the state. By World War I, the historic inn’s facilities were outdated, though. As such, many of its guestrooms were converted into offices or apartments. Fortunately, in 1953, owners who appreciated the inn’s significance acquired the hotel and began a restoration designed to preserve its colonial design. Local real estate developer Paul Pearson eventually acquired the Maryland Inn during the 1970s, and endeavored to leave his own mark upon the building. Renovating it thoroughly, he transformed the inn into one of Annapolis’ premier holiday destinations. He even installed the King of France Tavern inside the basement, which made the Maryland Inn one of the city’s best venues to hear live jazz performances. Today, the Maryland Inn continues to be among the most celebrated holiday destinations in downtown Annapolis, hosting hundreds of guests every year.

Governor Calvert House:

The building was originally a one-and-a-half story structure with a gambrel roof. Its earliest occupant, Charles Calvert, was cousin to the fifth Lord Baltimore and served as Governor of Maryland from 1720 to 1727. In 1764, much of the building was destroyed by a fire. In consequence, the Calvert family moved to the countryside. The remains of the house were incorporated into a two-story Gregorian-style building that was used as barracks by the State of Maryland until 1784. Between 1800 and 1854, the domicile changed hands three times until the mayor of Annapolis, Abram Claude, purchased it as his own residence. Claude enlarged the building and endowed it with Victorian-era features. The Governor Calvert House remained a private home throughout most of the 20th century. But in the 1970s, Paul Pearson acquired the site with the intent on making it a beautiful boutique hotel. Along with the Maryland Inn and The Robert Johnson House, Pearson transformed all three buildings into magnificent inns that offered nothing but the best in modern comfort. His later collaborations with Historic Annapolis led to the archaeological research that uncovered several architectural features of the original building. One of the most remarkable is the hypocaust—or greenhouse heating system—that was discovered in the basement of the building.

The Robert Johnson House:

In 1772, an Annapolis barber named Robert Johnson purchased town lot #73, which his grandson used to build a beautiful brick house a year later. Serving as the Johnson family residence for the next several decades, it eventually passed on to new owners by the mid-1850s. Yet, two additional buildings had encroached on the lot in that span of time. The Johnsons had sold a portion of the locale to Elizabeth Thompson in 1808, who many historians believe built the neighboring frame house at 1 School Street. The second building—5 School Street—was a two-story frame house that Archibald Chisolm constructed in the early 1790s. The three buildings continued to coexist for years. In 1880, The Robert Johnson House was acquired by William H. Bellis, a local tailor who operated a shop along Main Street. He died in 1902, leaving the building to his daughter, Maud Marrow. She also acquired 1 and 5 School Street, and converted all three structures into the Marrow Apartments. The Robert Johnson House continued to operate as the Marrow Apartments throughout most of the 20th century, until Paul Pearson purchased the location and renovated it into a luxurious boutique hotel during the 1970s.

-

About the Location +

Annapolis itself was originally founded by a band of exiled Puritans from the Colony of Virginia in 1649. The group specifically picked a plot of land some two miles north from the mouth of the Severn River to create a small community they christened as “Providence.” Led by Williams Stone, the settlers only resided in the area for a short amount of time, abandoning the site for a better protected harbor near Whitehall Bay. The new settlement the colonists created bore the name “Town at Proctor’s,” before eventually adopting “Anne Arundel’s Towne.” (Anne Arundel was the wife of Cecilus Calvert, the first Proprietor of the Province of Maryland.) The town itself served on the front lines of the English Civil War, staying loyal to the forces of King Charles I. Still, Parliamentarians seized the area, forcing William Stone and his “Cavaliers” to flee into Virginia. Despite some serious attempts to recapture the community, the Parliamentarians remained in control over Anne Arundel’s Towne until the restoration of the English Royal Family in 1660. Anne Arundel’s Towne continued to be a small coastal village for many years thereafter, even when royal authorities made the settlement the official colonial capital of Maryland during the late 1690s. The settlement quickly became the epicenter of all political and cultural life in the colony, epitomized by the founding of St. John’s College in 1696. In honor of its new designation as Maryland’s capital, Governor Francis Nicholson decided to rename the community “Annapolis” after the presumptive heir to the English throne, Princess Anne of Denmark and Norway. When Anne finally inherited the title of queen, she recognized Nicholson’s tribute and granted Annapolis a formal town charter in 1708.

The town began to grow exponentially throughout the rest of the 18th century, its expansion fueled greatly by the nascent regional maritime commerce. Among the most prolific aspects of its local economy involved commercial fishing and shipbuilding. Its wealth was reflected throughout the community through the creation of many beautiful municipal buildings and townhouses, which displayed some of the finest characteristics of colonial American architecture at the time. Annapolis even saw the debut of a prominent local newspaper called the Maryland Gazette. But the town slowly lost its status as Maryland’s premier port of entry to Baltimore, which had undergone its own renaissance toward the end of the century. But Annapolis retained much of its political importance nonetheless, serving as the site for the Congress of the Confederation immediately following the end of the American Revolutionary War. It was here that the Treaty of Paris was ratified to end the conflict, as well as the place where George Washington stoically surrendered control of the army to the national government. Later on in 1786, delegates from the states of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Delaware met in Annapolis to discuss the problems that had arisen due to the Articles of Confederation. Gathering during an event known to history as the “Annapolis Convention,” the politicians passed a resolution that agreed to amend the Articles of Confederation a year later in Philadelphia. The delegates who attended the second meeting—now known as the “Constitutional Convention”—eventually created the U.S. Constitution, thus establishing the current form of America’s federal republic. As such, some historians today consider the Annapolis Convention to be the precursor to the momentous Constitutional Convention!

Annapolis remained an important commercial port well into the 19th century, as evidenced by the creation of Fort Severn along the local shoreline in 1808. Fort Severn remained active for several decades until it was reborn as the prestigious U.S. Naval Academy shortly before the outbreak of the Mexican-American War. Extending for some 338 acres, the academy has since continued to train generations of aspiring naval officers for service in either the U.S. Navy of the Marine Corps. The city maintained an active role in the nation’s naval heritage in the following century as well, especially in regard to the modern national defense apparatus. Annapolis’ harbors teemed with temporary wharves and warehouses during World War II, where craftsmen worked tirelessly to build numerous of patrol torpedo boats for use all over the world. Those facilities remained active for many decades, too, constructing small auxiliary craft throughout both the Korean and Vietnam wars. Annapolis today is still one of Maryland’s most vibrant communities. It continues to function as the state’s capital, where both the Maryland General Assembly and the Governor of Maryland meet at the celebrated Maryland State House—the most historic building of its kinds in the entire country. It is also home to many other fascinating cultural institutions, such as the Banneker-Douglas Museum, the Annapolis Maritime Museum, the Hammond-Harwood House, and the William Paca House & Garden. Most of those landmarks are located in the Colonial Annapolis Historic District, which has several dozen wonderfully preserved residences that date back to before the American Revolution.

-

About the Architecture +

All of the historical buildings that constitute the Historic Inns of Annapolis stand as brilliant examples of American colonial architecture. Architectural historians today generally define American colonial architecture as covering a wide berth, subdividing it into categories like First Period English, French Colonial, Spanish Colonial, and Dutch Colonial. But most professionals believe that the aesthetics embraced by English—and later British—colonists to be the most ubiquitous, given their widespread cultural influence during America’s formative years. It dominated the architectural tastes of most Americans at the time, until the Federalist design principles overtook them in the 19th century. The style was especially predominant in New England, which quickly saw the creation of another two unique subtypes—Saltbox and Cape Cod-style. A different subset of English colonial architecture appeared within the southern colonies as well, which some experts refer to as “Southern Colonial.” The building style resembled the general trends embraced by other colonists in British America, although it differed in with its use of a central passageway, massive chimneys, and a hall and parlor. Nevertheless, all of the buildings shared strikingly similar qualities. American homes of the age were both simple and symmetrical, and made use of either wood, brick, or stone. Rectangular in shape, they typically extended either two to three stories in height. All of the formal parts of the home were located on the first floor, while the family bedrooms occupied the upper levels of the building. The floorplans were also fairly limited in scope, favoring to fill each level with just a couple of rooms. This simplicity was slowly modified by the arrival of Georgian-style architecture from Great Britain toward the end of the 18th century. Architects subsequently relied more upon mathematical ratios to achieve symmetry in their designs, and used, albeit with restraint, elements of classical architecture for ornamentation.

-

Famous Historic Events +

George Washington’s Resignation as Commander-in-Chief (1783): In the waning days of December 1783, the Congress of the Confederation gathered to hear an address from George Washington, who was then serving as Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army. He had just led the organization through seven years of difficult warfare, often resisting internal strife, poor supply lines, and harsh weather. More importantly, he had tackled the task of confronting the most professional fighting force in the world—the British Royal Army. Some suspected that when the war had finally stopped, Washington would hold onto his power and act as a dictator. But Washington harbored no such ill-will and asked the Congress how he should surrender his command. Congressional representatives responded that it may be fitting for the general to do so in public, to which Washington agreed. Congress quickly began planning the event under the guidance of Thomas Jefferson, Eldridge Gerry, and James McHenry. They specifically organized a massive dinner party in honor of Washington. Since the capital was only temporarily based in Annapolis, most of the delegates who planned on attending did not have a residence in the city. As such, quite a few of them reserved a guestroom inside the Maryland Inn.

Some 200 people joined the dinner, which was replete with lively dances and entertaining banter. A total of 13 toasts were dedicated to Washington (a symbolic gesture representing the original 13 states) before Washington himself toasted the representatives of Congress. The following day, Washington met the delegates inside the Maryland State House—then serving as a makeshift capitol building—to formally give up his military powers. Many observers noticed that Washington was rather emotional, with one delegate even commenting that his voice quivered frequently. Washington famously ended his speech by stating:

- “Having now finished the work assigned me, I retire from the great theatre of action, and bidding an affectionate farewell to this august body, under whose orders I have so long acted, I here offer my commission, and take my leave of all the employments of public life.”

After the President of the Congress, Thomas Mifflin, delivered a prepared response of thanks on behalf of the members, Washington bowed and left he chamber. Contrary to Washington’s thoughts, his career in public service was far from over—he would return once again when the nation elected him as its first president in 1789. But Washington’s surrender of the military affirmed the supremacy of democracy to govern the new nation. His surrender of the military into the hands of the Congress—a democratically elected civilian body—ensured that the people of America would always hold the authority to rule.

Paris Peace Treaty (1783): Support for the British war effort during the American Revolutionary War evaporated in Great Britain when the army of Lord Williams Cornwallis capitulated to the combined forces of General George Washington and the Comte de Rochambeau at the Siege of Yorktown. As such, Parliament begrudgingly agreed to enter into peace negotiations with their former colonists in the Thirteen Colonies. In response, the Congress of the Confederation sent a group of envoys to Europe in the spring of 1782 to discuss terms. Led by Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and John Jay, the American delegation pressed their claims for independence. Yet, the British representatives—who merely wanted an end to the hostilities—outright refused their demands and stalled the deal. Fortunately for the Americans, talks resumed after more sympathetic politicians took control of Parliament later that summer. (The new Prime Minister, Lord Shelburne, specifically saw independence as an opportunity to cultivate strong commercial ties with America before any of Great Britain’s European rivals.) While it still took several more months to resolve the details, the two sides eventually agreed to the following:

- British recognition of the newly created United States of America as a sovereign nation with clearly defined boundaries out to the Mississippi River and the Great Lakes region.

- Open navigation of the Mississippi to American citizens and British subjects who lived in the vicinity.

- Secured access of American mariners to the Newfoundland fisheries located off the coast of Canadian waters in the Great Banks.

- The ability of creditors in both nations to collect debts owed in each other’s respective countries.

- Protection and just treatment for those American colonists who had remained loyal to the British Crown during the war

Canada—long the obsession of American expansionists—remained a dominion of the British Empire. Other concessions made during the peace talks gave territorial rights to America’s allies: France, Spain, and The Netherlands. (Great Britain later consented to those terms in separate peace deals.) Even though the two delegations finally signed their agreement in Paris at the Hôtel d'York in September of 1783, the American representatives still needed to have Congress approve it. Gathering inside the Old Senate Chamber of the Maryland State House, the members formally ratified the Treaty of Paris on January 14, 1784, thus formally ending the American Revolutionary War. Interestingly, some of the delegates stayed at the Maryland Inn while they participated in the ratification process, as congressional representatives rarely had permanent accommodations wherever they did business. (The practice of using temporary lodgings would remain in effect for some time, even after the future federal government established Washington, D.C., as the permanent capital a decade later.)

Guest Historian Series

Nobody Asked Me, But…

Historic Inns of Annapolis (1727), Annapolis, Maryland

In the center of Annapolis, three historic inns have been combined to comprise the Historic Inns of Annapolis. They are the Maryland Inn, the Governor Calvert House and the Robert Johnson House as well as the Treaty of Paris restaurant and the King of France Tavern.

•The Maryland Inn

The Maryland Inn was built in 1776 as private residence by Thomas Hyde, a respected merchant and civic leader. When he advertised it for sale in 1782, it was described as "an elegant brick house adjoining Church Circle in a dry and healthy part of the city. This house is one hundred- feet front, three-story height, has 20 fireplaces and is one of the first houses in the state for a house of entertainment."

In 1784, Sarah Ball, who had become this historic inn's manager advertised that she ".... has opened a tavern at the house formerly kept by her, fronting Church (now Duke of Gloucester) Street; and having supplied herself with everything necessary and convenient, she solicits the favors of her old customers and the public is general..."

The inn remained a popular place for lodging throughout the 19th century. It was acquired by the Maryland Hotel Company in 1868 and remained the most prominent Annapolis hotel and the favorite rendezvous for important national state and military visitors. By World War I, the historic inn's facilities were outmoded and many of its rooms were converted into offices and apartments.

There were several proprietors over the next several decades, and in 1953, owners who appreciated the inn's importance in Maryland's history acquired the hotel and began a restoration designed to preserve its Colonial design and to provide modern amenities.

• Governor Calvert House

The house originally built at 58 State Circle was a one-and-a-half story structure with a gambrel roof. Its earliest occupant, Charles Calvert, was cousin to the fifth Lord Baltimore and governor of Maryland from 1720-1727.

In 1764, much of the building was destroyed by fire, and the Calverts moved to the country. The remains of the house were incorporated into a two-story Gregorian-style building that was used until 1784 as barracks by the state of Maryland.

Between 1800 and 1854 the destination changed hands three times until the mayor of Annapolis, Abram Claude, purchased it. Claude enlarged the building and endowed it with Victorian features.

The house was privately owned through the 1900s until Paul Pearson acquired it and proposed plans for its restoration and expansion into a large historic inn. His collaboration with Historic Annapolis led to the archaeological research that uncovered several architectural features of the original building. One of the most remarkable is the hypocaust, or greenhouse heating system, that was discovered in the basement of the building.

• The Robert Johnson House

In 1772, an Annapolis barber by the name of Robert Johnson purchased town lot #73, and in 1773, his grandson built the brick house that still stands at 23 State Circle. The main brick house remained with Johnson heirs until around 1856. A portion of the lot was sold in 1808 to Elizabeth Thompson, who probably built the frame house at 1 School Street.

The third building on the lot, 5 School Street, was two-story frame house built between 1790-1792 by Archibald Chisolm, who kept the destination until 1811.

In 1880, William H. Bellis purchased the Johnson house and opened a tailor shop facing Main Street. He died in 1902, leaving 23 State Circle to his daughter Maud Morrow. She acquired 1 and 5 School Street, and converted the building into the Morrow Apartments. Later the Historic Inns purchased the destination and converted it into a historic hotel in Annapolis. All three inns underwent a multimillion dollar renovation of their guestrooms and key public areas in 2006.

In 2005, Annapolis was named one of America's Dozen Distinctive Destinations by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. The Historic Inns of Annapolis are designated as Historic Hotels of America.

*****

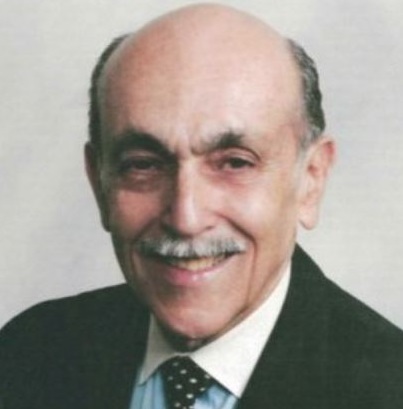

About Stanley Turkel, CMHS

Stanley Turkel is a recognized consultant in the hotel industry. He operates his hotel consulting practice serving as an expert witness in hotel-related cases and providing asset management an and hotel franchising consultation. Prior to forming his hotel consulting firm, Turkel was the Product Line Manager for worldwide Hotel/Motel Operations at the International Telephone & Telegraph Co. overseeing the Sheraton Corporation of America. Before joining IT&T, he was the Resident Manager of the Americana Hotel (1842 Rooms), General Manager of the Drake Hotel (680 Rooms) and General Manager of the Summit Hotel (762 Rooms), all in New York City. He serves as a Friend of the Tisch Center and lectures at the NYU Tisch Center for Hospitality and Tourism. He is certified as a Master Hotel Supplier Emeritus by the Educational Institute of the American Hotel and Lodging Association. He served for eleven years as Chairman of the Board of the Trustees of the City Club of New York and is now the Honorary Chairman.

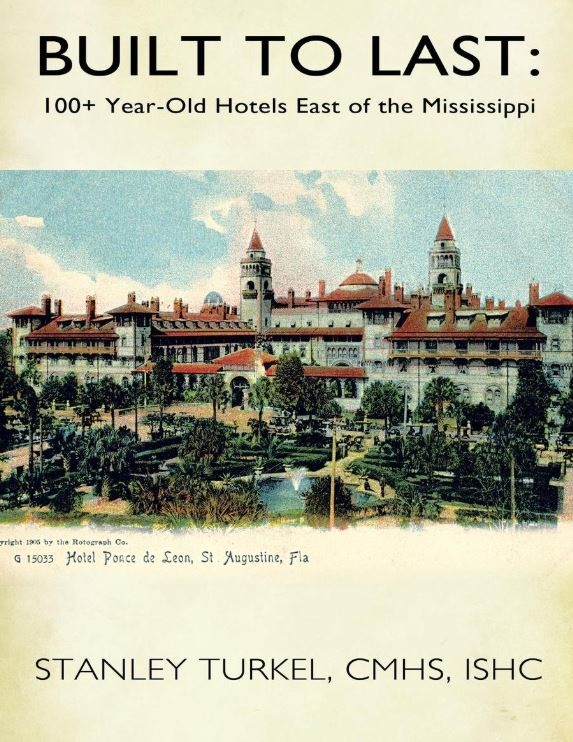

Stanley Turkel is one of the most widely-published authors in the hospitality field. More than 275 articles on various hotel subjects have been posted in hotel magazines and on the Hotel-Online, Blue MauMau, Hotel News Resource and eTurboNews websites. Two of his hotel books have been promoted, distributed and sold by the American Hotel & Lodging Educational Institute (Great American Hoteliers: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry and Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels East of the Mississippi). A third hotel book (Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels in New York) was called "passionate and informative" by the New York Times. Executive Vice President of Historic Hotels of America, Lawrence Horwitz, has even praised one book, Great American Hoteliers Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry:

- “If you have ever been in a hotel, as a guest, attended a conference, enjoyed a romantic dinner, celebrated a special occasion, or worked as a hotelier in the front or back of the house, Great American Hoteliers, Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry is a must read book. This book is recommended for any business person, entrepreneur, student, or aspiring hotelier. This book is an excellent history book with insights into seventeen of the great innovators and visionaries of the hotel industry and their inspirational stories.”

Turkel was designated as the “2014 Historian of the Year by Historic Hotels of America,” the official program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. This award is presented to an individual for making a unique contribution in the research and presentation of history and whose work has encouraged a wide discussion, greater understanding and enthusiasm for American History.

Works published by Stanley Turkel include:

- Heroes of the American Reconstruction (2005)

- Great American Hoteliers: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2009)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels in New York (2011)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels East of the Mississippi (2013)

- Hotel Mavens: Lucius M. Boomer, George C. Boldt and Oscar of the Waldorf (2014)

- Great American Hoteliers Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2016)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels West of the Mississippi (2017)

- Hotel Mavens Volume 2: Henry Morrison Flagler, Henry Bradley Plant, Carl Graham Fisher (2018)

- Great American Hotel Architects Volume 1 (2019)

- Hotel Mavens Volume 3: Bob and Larry Tisch, Curt Strand, Ralph Hitz, Cesar Ritz, Raymond Orteig (2020)

Most of these books can be ordered from AuthorHouse—(except Heroes of the American Reconstruction, which can be ordered from McFarland)—by visiting www.stanleyturkel.com, or by clicking on the book’s title.