Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

Discover Martinique New York on Broadway, which features exceptional French Renaissance detail designed by esteemed architect Henry Hardenbergh.

Martinique New York on Broadway, Curio Collection by Hilton, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2010, dates back to 1896.

VIEW TIMELINEUnfortunately, the initial appeal of Martinique was not destined to last forever. By the 1950s, the concentration of New York’s many theatres moved several blocks away from the hotel to Times Square. Furthermore, its amenities had significantly fallen behind many of its competitors, with its guestrooms not even possessing their own separate baths. The lack of interest with the hotel became so great that the City of New York leased the building for use as a short-term homeless shelter. Living conditions inside the structure declined rapidly and the destination soon developed a notorious reputation throughout the entire city. In 1989, developer Harold Thurman purchased the ailing building after municipal officials relocated its tenants to another domicile. Yet, Martinique continued to sit dormant for several more years until it finally relaunched as part of the Holiday Inn brand in 1998. Reopening to great acclaim as the “Holiday Inn Martinique on Broadway,” it continued to function as a member of the company before rebranding as a Radisson hotel seven years later. Today, Hilton Worldwide operates this wonderful historic hotel within its prestigious Curio Collection, calling it “Martinique New York on Broadway, Curio Collection by Hilton.” This stunning historic hotel continues to attract hundreds of guests from across the globe due to its unrivaled elegance and spectacular service. Ownership has even done an amazing job preserving its heritage, making it one of the foremost historic hotels in New York City. Martinique New York has even received awards from Historic Hotels of America in recognition of its history of hospitality, earning the title of “Best Historic Hotel (Over 400 Guestroom)” in 2020 and “Best City Center Historic Hotel” in 2023. Their property historian, Tara Williams, won “Hotel Historian of the Year” in 2025.

-

About the Location +

Martinique New York on Broadway, Curio Collection by Hilton, specifically resides in the heart of Midtown Manhattan, one of New York City’s most famous areas. Home to renowned landmarks like Central Park, Times Square, and Carnegie Hall, the locale is the central portion to the greater borough of Manhattan. Often described today as the cultural capital of the world, Manhattan’s origins are actually quite humble. The Lenape Native Americans had long inhabited the region for centuries, referring to it as “manaháhtaan,” or, “the place for gathering wood to make bows.” But in 1609, Henry Hudson—and English explorer working on behalf of the Dutch East India Company—became the first European to chart Manhattan’s coastline (which was also an island). The Dutch had hoped Hudson could locate the mythical “Northwest Passage,” a maritime route that was believed to cut through the North American landmass straight to China. Despite Hudson’s failure in locating the illusive body of water, the Dutch nevertheless took his findings to establish a colony in 1625. Building a citadel called “Fort Amsterdam” at the southernmost tip of the Manhattan, the Dutch eventually used the island to serve as the economic hub for their settlement of New Amsterdam. (According to one merchant, Pieter Janszoon Schagen, the first colonists to arrive apparently paid the Lenape for the island in exchange for a fixed sum of Dutch guilders.) New Amsterdam quickly emerged as an important hub for trade between the Caribbean, Europe, and several other North American colonies. It remained under Dutch authority for the next four decades, until the English managed to wrestle control away during the Second Anglo-Dutch War of the 1660s. Despite a brief moment in which the Dutch recaptured Manhattan a decade later, the island continued to be an English colony, becoming the heart of the newly created Province of New York. As such, the community on Manhattan Island was renamed as “New York City.”

Manhattan and the surrounding communities near New York Harbor steadily grew as a prosperous seaport under English rule. It became a focus for development in the “New World,” with both Columbia University and The King’s College being founded during the period. The area continued to play an important role in New York, especially during the American Revolution. The island became a hotbed for patriotic sentiment, with the Sons of Liberty organizing in the city to protest British efforts on taxation without representation. Dozens of revolutionaries even met in Manhattan to hold a Stamp Act Congress, which constituted the first formal effort by Americans to resist the colonial authorities. Its socioeconomic significance also made it an early military target of the United Kingdom when fighting finally broke out between the two sides in the mid-1770s. In fact, the British attempted to seize it in 1776 during the New York Campaign. George Washington and the Continental Army were unfortunately forced to abandon Manhattan and its bustling port at the climax of the campaign, which transpired with the defeats at the Battle of Fort Washington and the Battle of Long Island. Manhattan remained occupied by the British for the remainder of the war, functioning as the main headquarters for its various military expeditions active throughout the colonies. And once the fighting had stopped in the early 1780s, the region became the fifth national capital for the infant United States of America under the Articles of Confederation. Delegates to the Continental Congress subsequently met at New York City Hall in Lower Manhattan, which at the time was located inside a local business called “Fraunces Tavern.” Manhattan remained the capital of the nation once the U.S. Constitution was enacted in 1789, gathering inside the now famous “Federal Hall.” Federal Hall specifically served as the site where the federalized U.S. Congress and the U.S. Supreme Court met, as well as the place where both the Bill of Rights and Northwest Ordinances were ratified!

Even though Manhattan ceased serving as the nation’s capital a year later, it remained a vibrant economic center well into the 19th century. Thanks to the financial policies of Founding Father Alexander Hamilton (who also called New York City his home) and the development of the Erie Canal, New York City emerged as the main port for any goods heading toward either Canada or the American Midwest. The New York Stock Exchange on Wall Street matured greatly as a result, evolving into one of the nation’s leading financial institutions. Its population exploded, surpassing Philadelphia in both size and prosperity. Its wealth of economic opportunities made it a desirable destination for all kinds of immigrants, beginning first with German and Irish people and later Southern and Eastern Europeans. Manhattan thus became densely populated toward the end of the century, with hundreds of tenement houses lining most of its local neighborhoods. Yet, the presence of so many immigrant families in Manhattan led to the development of numerous ethnic enclaves—like Little Italy—as well as the perception that the island was a beckon for those wishing to gain a better life in the United States. (This vision even inspired the French to donate the Statue of Liberty to America in 1886.) Manhattan continued to attract waves of migrant peoples into the 20th century, as well, specifically African Americans who relocated to the area as part of the Great Migration of the 1920s. This led to the birth of the celebrated Harlem Renaissance, which was an intellectual movement that saw the cultural revival of African American art and literature in the United States. Although it was concentrated in the Manhattan neighborhood of Harlem, its influence was so great that it affected black artists, musicians, and writers across the globe.

With millions of people thus living in Manhattan by the late 1890s, city officials decided to unite the nearby communities in Brooklyn, Queens, Westchester, and Richmond counties to form the “City of Greater New York.” But the island became the site for another equally important historical development—industrialization. Around the same time that modern New York City emerged, many capitalists and entrepreneurs began financing the construction of massive factories and skyscrapers all over Manhattan. The island’s skyline transformed significantly during the first few decades of the 20th century, with such famous landmarks—including the Chrysler Building, Grand Central Terminal, and 30 Rockefeller Plaza—opening within that span of time. Yet, its most iconic feature was the Art Deco-inspired Empire State Building. (It is also located right down the road from Martinique!) Yet, Manhattan also saw the creation of many luxurious storefronts, restaurants, and art galleries, which started attracting tourists from across the country. Some of the most opulent buildings to debut were the theaters and concert halls along Broadway, one of Manhattan’s major thoroughfares. Soon known as the “Theatre District,” sections of Broadway quickly became synonymous with nightlife in the city. By the end of the 20th century, Manhattan and the rest of New York City had firmly established themselves as the most influential urban center in the whole United States. Today, Manhattan has maintained its prestigious status as a national cultural destination. It is home to many fantastic upscale apartment complexes and townhouses in such renowned neighborhoods like SoHo, the Upper West Side, the Upper East Side, and Greenwich Village (which is also home to the modern LGBT rights movement in America). Many prominent corporations, such as JP Morgan Chase, Bloomberg L.P., Deloitte, MetLife, and Viacom are headquartered in the borough. Four of the nation’s biggest television networks—ABC, CBS, FOX, and NBC—are also based in Manhattan, as well. Some of the best vendors also have stores on Fifth Avenue, too, making it a shopping paradise. Even the headquarters for the United Nations is based in Manhattan. Few other places can claim to possess such a heritage than either Manhattan or New York City as a whole.

-

About the Architecture +

William R. H. Martin spared no expense when he originally began constructing Martinique New York on Broadway, Curio Collection by Hilton. To ensure that it appeared as beautiful as possible, he commissioned the renowned Henry Janeway Hardenbergh to craft its magnificent design. Hardenbergh had already developed a strong reputation as an accomplished architect for his work on many other structures throughout the greater New York metropolitan area, including the likes of The Dakota Apartments, Hotel Albert, and the Schermerhorn Building. Many contemporaries regarded his designs for both the Waldorf Hotel and the Astoria Hotel in Midtown Manhattan to be his some of his best at the time. (Both buildings were eventually demolished to make way for the Empire State Building.) Hardenbergh decided to design Martinique with “French Renaissance Revival.” Sometimes referred to as “Neo-Renaissance,” Renaissance Revival architecture in general is a group of architecture revival styles that date back to the 19th century. Neither Grecian nor Gothic in their appearance, Renaissance Revival-style architecture drew inspiration from a wide range of structural motifs found throughout Early Modern Western Europe. Architects in France and Italy were the first to embrace the artistic movement, who saw the architectural forms of the European Renaissance as an opportunity to reinvigorate a sense of civic pride throughout their communities. As such, those intellectuals incorporated the colonnades and low-pitched roofs of Renaissance-era buildings, with the characteristics of Mannerist and Baroque-themed architecture. Perhaps the greatest structural component to a Renaissance Revival-style building involved the installation of a grand staircase in a vein similar to those located at the Château de Blois and the Château de Chambord. This particular feature served as a central focal point for the design, often directing guests to a magnificent lobby or exterior courtyard. Yet, the nebulous nature of Renaissance Revival architecture meant that its appearance varied widely across Europe. Historians today, thus, often find it difficult to provide a specific definition for the architectural movement.

-

Famous Historic Events +

Creation of the Professional Golf Association (1916): Popularity with golf was reaching new heights at the start of the 20th century, as thousands of ordinary Americans began playing the sport at courses across the nation. Recognizing the economic potential that such interested possessed, amateur player Tom McNamara endeavored to create an organizational body that could help grow the sport in a professional manner. McNamara acted on his dream in January of 1916, convincing his business partner, Rodman Wanamaker, to sponsor a meeting where the topic could be discussed among a group of influential golfers. Wanamaker enthusiastically embraced McNamara’s idea as the perfect way to market his upscale department store in Midtown Manhattan. Wanamaker himself was specifically locked in a bitter battle over the sale of golf balls with A.G. Spaulding & Bros, and saw the gathering as a great marketing opportunity. The two decided to invite several dozen golfers to a special luncheon hosted by the Taplow Club, which McNamara operated on Wanamaker’s behalf inside his store. Many of the most well-known golf personalities attended, including Francis Ouimet, James Maiden, Alex Smith, and A.W. Tillinghast. When all the delegates had finally arrived, both Wanamaker and McNamara petitioned them to make golf a professional business governed by an administrative body. Furthermore, the two men believed that such an organization would enhance their social standing as professional athletes.

Wanamaker specifically proposed hosting a series of match-play tournaments that could showcase the combined talent of those who joined the group. To sweeten the proposition, Wanamaker stated that he would create an official trophy and donate some 2,500 dollars in prize money. All travel expenses for tournament participants would even be covered by Wanamaker himself. Concluding his argument, Wanamaker suggested that they call their new organization the “Professional Golfers’ Association of America” and the competition, the “PGA Championship.” While Wanamaker initially wished to have the group work closely in unison with the United States Golf Association, many in attendance voted to have the Professional Golfers’ Association of America to operate as a separate entity. All the members demonstratively shared McNamara’s and Wanamaker’s enthusiasm though, agreeing to meet again the following day to create the organization’s bylaws. Several more meetings transpired over the next several months, culminating with a final one at Martinique on April 10. Gathering inside the hotel’s second-floor boardroom, the delegates formally charted the Professional Golfers’ Association of America and elected 78 members to serve in various positions within the group. The Professional Golfers’ Association of America has since become one of the most august organizations for the sport of golf in the entire world, having grown to number 29,000 members at the present. The group was even responsible for creating the immensely popular PGA Tour, which it originally founded as a separate tournament in the late 1960s.

-

Famous Historic Guests +

Gus Edwards, prominent vaudeville actor and playwright.

Walter Hagen, winner of 11 major golf championships that include the PGA Championship and the U.S. Open.

Francis Ouimet, winner of the U.S. Open in 1913 and regarded as the “father of amateur golf.”

A.W. Tillinghast, one of the most prolific golf course architects in American history.

Henry F. Young, silent film actor known for his outrageous stunts.

George Barr McCutcheon, novelist and playwright known for his book, Brewster’s Millions.

Guest Historian Series

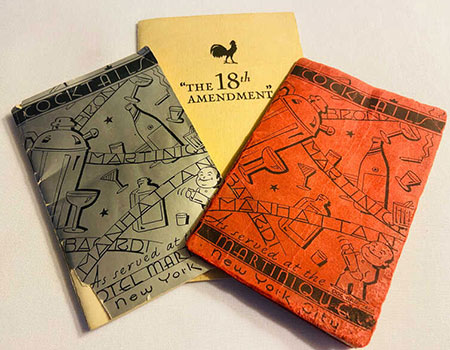

Nobody Asked Me, But...No. 270;

Hotel History: Martinique New York on Broadway, Curio Collection by Hilton (1896), New York, New York*

By Stanley Turkel, CMHS

The Hotel Martinique (560 rooms) at the northeast corner of Broadway and 32nd Street was constructed in three phases in 1897-98, 1901-03 and 1909-11. Developer William R. H. Martin built and expanded his hotel because the center of theater life had moved up Broadway to 39th Street where the Metropolitan Opera House had been built in 1883. Martin hired the distinguished architect Henry Janeway Hardenbergh (1874-1918).

Hardenbergh, who began his own architectural practice in New York in 1870, became one of the city’s most distinguished architects. Recognized for their picturesque compositions and his buildings often took their inspiration from the French, Dutch, and German Renaissance styles.

Hardenbergh is best known for his luxury hotel and apartment house designs. Among the earliest of these are the Dakota Apartments (a designated New York City Landmark) and the Hotel Albert, now Albert Apartments. His earliest midtown hotels, the original Waldorf-Astoria (Fifth Avenue and West 34th Street), and the Manhattan Hotel (Madison and East 42nd Street) have all been demolished, but when constructed they set the standard for luxury hotel design, both the exterior and interior. Hardenbergh continued to perfect his luxury hotel designs in the Plaza Hotel (a designated New York City Landmark), and in Washington, D. C., at the Raleigh Hotel (demolished).

The owner and developer of Martinique Hotel was William R. H. Martin, a large landowner in Manhattan at the turn of the century and a founding member of the clothing firm of Rogers, Peet & Company. Martin was born in St. Louis and lived in Brooklyn as a child. He entered the clothing business with his father John T. Martin, who had been a large army contractor during the Civil War. Later the Martins formed a wholesale clothing business with Marvin Rogers; it was known by several different names before becoming Rogers, Peet & Co. Martin served as head of the company from 1877, but had retired from active involvement several years before his death in 1912. Martin used his wealth to invest heavily in Manhattan real estate, and at the time of his death his holdings were valued at more than ten million dollars. These investments included such locations as the Marbridge Building as well as Martinique Hotel. Martin also built and supported the Trowmart Inn, a home for working girls.

Martin clearly thought the 34th Street-Broadway area was a vital, growing section for business and investment. Rogers, Peet & Co. opened a store at 1260 Broadway in 1889, even before such big department stores as Macy’s and Saks moved to 34th Street. Martin chose to build his new hotel close to Greeley and Herald Squares because the location was beginning to offer many opportunities for shopping, theater and restaurants to attract the tourist trade, and was close to several modes of transportation.

Hardenbergh created a French Renaissance design which capitalized on the openness of Greeley Square with a boldly-scaled mansard roof, towers and ornate dormers. The façade reflects Hardenbergh’s reputation for designing buildings for long-term use, not short-term profit. The glazed brick, terracotta-and limestone-clad structure also features stonework, balconies and prominent cartouches on all three of its main facades.

The Hotel Martinique opened on December 21, 1910, with a total of 600 rooms. It was well-located within walking distance from the newly-opened Pennsylvania Station, Macy’s on Herald Square (which opened in 1904) and the PATH commuter railroad system’s Manhattan terminus at 33rd Street (1907). Across the street from Martinique was the Gimbels New York flagship department store. Designed by Daniel Burnham, the structure offered 27 acres of selling space. When this building opened in 1910, a major selling point was its many doors leading to the Herald Square subway station. Doors also opened upon a pedestrian passage under 33rd Street, connecting Penn Station to those subway stations. The idea of a Thanksgiving Day parade originated in 1920 with Gimbels Department Store in Philadelphia. Macy’s in New York did not start its parade until 1924.

A faded old Martinique brochure from 1910 contains the following information:

- "The Hotel Martinique is located at the intersection of Broadway, Sixth Avenue and 32nd Street, and the plaza thus formed is termed Herald or Greeley Square….One block east is Fifth Avenue, the great residential street of New York. Within a radius of three blocks are to be found the greatest of the city’s retail stores, making it an ideal headquarters for shoppers. The best theaters are centered in this vicinity, and the two great Opera Houses are within easy walking distance…The Gentlemen’s Broadway Café is a veritable architectural gem. The walls and columns of Italian marble give to this room a richness which is completed by Pompeiian panels of unquestioned merit."

The brochure goes on to report that Martinique towered over all adjacent structures, “furnishing views and the degree of light seldom secured in a city hotel. The sanitary precautions, plumbing, etc. are the most complete.” Prices for rooms, according to the brochure, were $3.50 a day for room and bath, $6.00 and up for bedroom, bath, and parlor.

Near the end of the 19th century, the area of Broadway and West 34th Street gained prominence as an important entertainment district. By the 1860s, the most fashionable playhouses and the Academy of Music were located near Union Square. The construction of Madison Square Garden brought New York’s entertainment district up to 23rd Street, along with the fashionable shopping establishments of the Ladies Mile, hotels, and restaurants. By the 1880s Broadway, between 23rd and 42nd Street became New York’s glittering “Great White Way” which was lined with theaters and elegant department stores.

Restaurants and luxurious hotels followed, serving the many visitors who flocked to this part of town. The Metropolitan Opera House, located at Broadway and 39th Street opened in 1883, and sparked a theatrical move uptown. The Casino Theater, the Manhattan Opera House, and Harrigan’s (later the Herald Square Theater) were all located nearby. In 1893, the Empire Theatre opened at Broadway and West 41st Street, sparking further development in the area of Longacre Square (later called Times Square). Saks & Co, Gimbels and R.H. Macy’s anchored the shopping at 34th Street beginning in 1901-02. Restaurants such as Rector’s and Delmonico’s satisfied the gastronomical needs of New York’s wealthy, while they stayed at such hotels as the Marlborough, the Normandie, and the Vendome.

To the east, Fifth Avenue had a different tone, set by the establishment of B. Altman’s vast department store and the Gorham Silver Company, as well as the Knickerbocker Club. This was confirmed by the opening, in 1893 and 1897, of the lavish Waldorf and then the Astoria Hotels on Fifth Avenue, between 33rd and 34th Streets. One block to the west of Greeley Square, the planned Pennsylvania Station promoted much future development. Sixth Avenue and 34th Street was also the site of cross-town streetcars, the Sixth Avenue elevated, and the Hudson Tubes to New Jersey.

But when the theater district moved uptown to the Times Square area and the best stores left Sixth Avenue for Fifth Avenue, Martinique lost business and gradually became a delinquent hotel. By 1970, the Hotel Martinique, still in private ownership, was renting rooms to New York City and the Red Cross for use as emergency housing for homeless people. For nearly 20 years, it served as one of New York’s most notorious welfare hotels.

After years of bad publicity, the city decided to empty the hotel with its dimly lit, squalid rooms and corridors and problems with lead paint and asbestos removal. (To get the full impact of the dreadful living conditions, read “Rachel and Her Children” by Jonathan Kozol which details the crowding, lack of services and corruption which created a nightmare for family groups.) When the last welfare family left Martinique in 1989, the hotel was acquired from Season Affiliates in a 99-year lease by Harold Thurman, who owned the Hilton Hotel at JFK International Airport. It remained vacant until 1996 while Thurman renovated the hotel completely and secured a Holiday Inn franchise.

On May 5, 1998, in a move that provided reminders of its past glory, Martinique was conferred landmark status by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Jennifer J. Raab, chairwoman of the Commission, said that they began considering landmark status out of concern that the new owner would seek to alter its exterior.

Here is a summary of the Commission’s report:

- "The Hotel Martinique, a major work of the prominent designer Henry J. Hardenbergh, was constructed in three phases, in 1897-98, 1901-03, and 1909-11. Developer William R. H. Martin, who had invested heavily in real estate in this area of the city, built and expanded the hotel in response to the growth of entertainment, shopping, and transportation activities in this busy midtown section. Martin hired the distinguished architect Henry J. Hardenbergh, who had acquired a reputation for his luxury hotel designs, including the original Waldorf and Astoria Hotels, as well as the Plaza. In his hotel and apartment house designs, Hardenbergh created picturesque compositions based on Beaux-Arts precedents, giving special care to interior planning and appointments. For the sixteen-story, French Renaissance-inspired style Hotel Martinique, the architect capitalized on the openness made possible by Greeley Square, to show off the building’s boldly-scaled mansard roof, with its towers, and ornate dormers. The glazed brick, terra cotta, and limestone-clad structure also features rusticated stonework, balconies and prominent cartouches on all three of its main facades: Broadway, 32nd Street and 33rd Street."

The hotel is now called Martinique New York on Broadway, Curio Collection by Hilton, and, against all odds, remains a stunning Beaux-Arts landmark building in the heart of midtown Manhattan just blocks away from the Empire State Building, Madison Square Garden, Penn Station, Macy’s, and the Chelsea art galleries and restaurants.

*****

About Stanley Turkel, CMHS

Stanley Turkel is a recognized consultant in the hotel industry. He operates his hotel consulting practice serving as an expert witness in hotel-related cases and providing asset management an and hotel franchising consultation. Prior to forming his hotel consulting firm, Turkel was the Product Line Manager for worldwide Hotel/Motel Operations at the International Telephone & Telegraph Co. overseeing the Sheraton Corporation of America. Before joining IT&T, he was the Resident Manager of the Americana Hotel (1842 Rooms), General Manager of the Drake Hotel (680 Rooms) and General Manager of the Summit Hotel (762 Rooms), all in New York City. He serves as a Friend of the Tisch Center and lectures at the NYU Tisch Center for Hospitality and Tourism. He is certified as a Master Hotel Supplier Emeritus by the Educational Institute of the American Hotel and Lodging Association. He served for eleven years as Chairman of the Board of the Trustees of the City Club of New York and is now the Honorary Chairman.

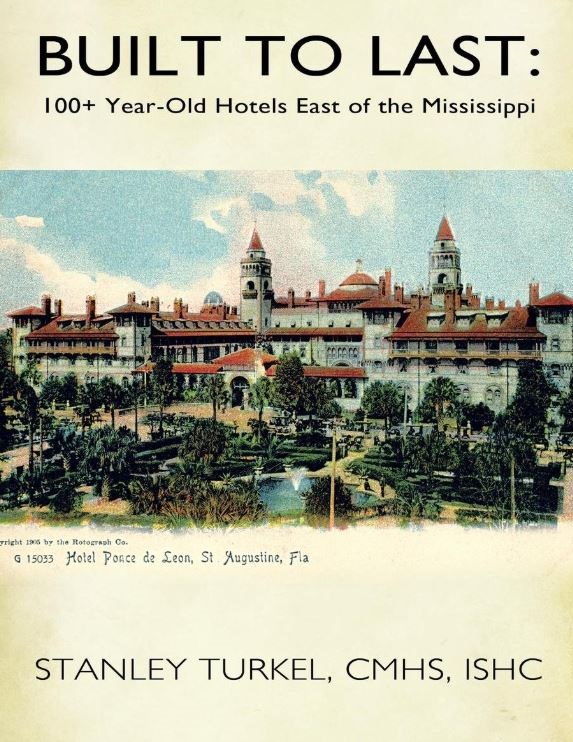

Stanley Turkel is one of the most widely-published authors in the hospitality field. More than 275 articles on various hotel subjects have been posted in hotel magazines and on the Hotel-Online, Blue MauMau, Hotel News Resource and eTurboNews websites. Two of his hotel books have been promoted, distributed and sold by the American Hotel & Lodging Educational Institute (Great American Hoteliers: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry and Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels East of the Mississippi). A third hotel book (Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels in New York) was called "passionate and informative" by the New York Times. Executive Vice President of Historic Hotels of America, Lawrence Horwitz, has even praised one book, Great American Hoteliers Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry:

- “If you have ever been in a hotel, as a guest, attended a conference, enjoyed a romantic dinner, celebrated a special occasion, or worked as a hotelier in the front or back of the house, Great American Hoteliers, Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry is a must read book. This book is recommended for any business person, entrepreneur, student, or aspiring hotelier. This book is an excellent history book with insights into seventeen of the great innovators and visionaries of the hotel industry and their inspirational stories.”

Turkel was designated as the “2014 Historian of the Year by Historic Hotels of America,” the official program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. This award is presented to an individual for making a unique contribution in the research and presentation of history and whose work has encouraged a wide discussion, greater understanding and enthusiasm for American History.

Works published by Stanley Turkel include:

- Heroes of the American Reconstruction (2005)

- Great American Hoteliers: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2009)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels in New York (2011)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels East of the Mississippi (2013)

- Hotel Mavens: Lucius M. Boomer, George C. Boldt and Oscar of the Waldorf (2014)

- Great American Hoteliers Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2016)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels West of the Mississippi (2017)

- Hotel Mavens Volume 2: Henry Morrison Flagler, Henry Bradley Plant, Carl Graham Fisher (2018)

- Great American Hotel Architects Volume 1 (2019)

- Hotel Mavens Volume 3: Bob and Larry Tisch, Curt Strand, Ralph Hitz, Cesar Ritz, Raymond Orteig (2020)

Most of these books can be ordered from AuthorHouse—(except Heroes of the American Reconstruction, which can be ordered from McFarland)—by visiting www.stanleyturkel.com, or by clicking on the book’s title.