Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

the story of a historic hotel in napa

Discover the Napa River Inn, built on the last vestiges of Napa City’s Main Street industrial commercial center. Today those buildings anchor the Napa River Inn.

Napa River Inn, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2004, dates back to 1884.

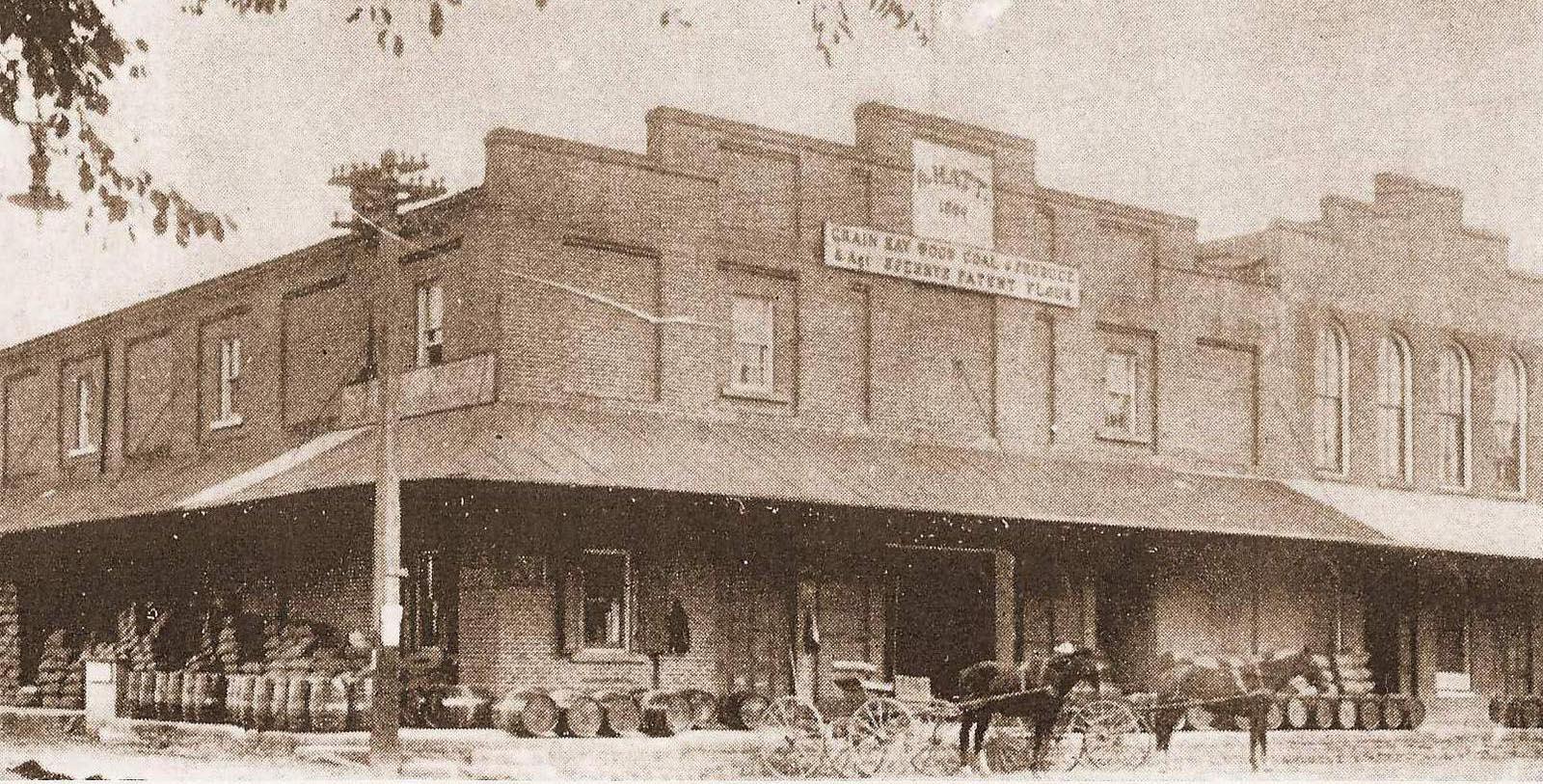

VIEW TIMELINEA member of Historic Hotels of America since 2004, the Napa River Inn is a brilliant historic landmark tucked away in California’s verdant Wine Country. Yet, this spectacular vacation getaway has not always been a boutique hotel. Indeed, the Napa River Inn was once known as the “Hatt Building” for decades. It was first constructed by Captain Albert E. Hatt, who was originally a native of Germany that immigrated to the Napa Valley in the mid-19th century. Arriving to the United States in 1859, Hatt initially made a living by operating a boat on the Sacramento River. Along the way, Captain Hatt married Alma Hogan, and together, they had six children. The two eventually acquired enough capital to relocate their family to Napa some three decades later. But Hatt was restless. Hungry for more success, Hatt decided to construct a massive warehouse in the center of town near the Napa River. Napa itself was a bustling industrial city back in the 1880s, with many factories operating near the river. As such, Hatt believed that the local merchants would jump at the opportunity to use his prospective warehouse as a storeroom. In 1882, Hatt purchased a sizeable plot of land at the intersection of Main and Fifth Streets from a landowner named William H. Coombs. Taking two years to design and construct, the two-story “Hatt Building” debuted to great acclaim. Its eclectic architectural appearance immediately made the warehouse a cherished local icon. Interestingly, Hatt had also built a skating rink on the second floor, which he later outfitted with White Rock maple planking imported directly from Chicago. Alma Hatt even opened a locally esteemed dining establishment that she called the “Oyster House and Restaurant.”

Hatt’s new business proved to be an incredible success, inspiring him to construct a second warehouse in 1887. Connected to the original structure, the new building was essentially a converted silo that had held all kinds of grain. Nevertheless, local business owners kept relying upon the complex to house many different products. Hatt himself even used the complex from time to time, in order to sell his own supply of coal, feed, produce, and other materials. The skating rink continued to be a popular attraction in Napa, too, as it accommodated all kinds of dances and parties. And in some cases, the facility even featured ornate obstacle courses for the public to try. Other spaces on the second floor became known as “Hatt Hall,” which had its own library, an anteroom, and a dining area. It, too, wound up hosting large social events like community galas and banquets. But with his wife’s death in 1899, Captain Hatt decided to leave the daily operations of the family business to his son, Albert Hatt Jr. The string of misfortune continued for the Hatt family, though, as Albert Hatt Jr.’s own spouse, Margaret, died in 1906. Overwhelmed from managing the enterprise alone, Albert Hatt Jr. himself passed away from stress in 1912. In the wake of his son’s death, Captain Albert E. Hatt sold the facility to the Keig family. They, in turn, operated the “Napa Mill” inside the location for the next several decades. In essence, the buildings became an exclusive granary and mill that produced various kinds of feed for the area’s local farmers.

Managed by a group of brothers in the Keig family, the Napa Mill was eventually run solely by Robert Edward Keig. Keig’s own son soon inherited the business, but decided close the facility during the mid-1970s. Despite gaining a listing on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places, the fate of the site appeared uncertain for years. Various real estate developers suggested numerous plans for the complex, but none ever came to fruition. Fortunately, salvation arrived in the form of Harry Price, who bought the location in 1992. Unlike his predecessors, Price hoped to transform the Hatt Building into a stunning hotel that would epitomize the grandeur of Napa Valley. Yet, he was also committed to preserving the facility’s rich architectural integrity, and endeavored to save as much of the historic complex as possible. For instance, some of the milling equipment, as well as the silo, still exist on the grounds today. After several long years, the Hatt Building debuted as the “Napa River Inn” on June 9, 2000. The grand opening of the Napa River Inn happened to coincide with the gradual rebirth of downtown Napa, which had occurred for some years prior. The hotel has since acted as one of the main economic engines revitalizing Napa’s historic downtown. As such, this fantastic historical attraction is certain to provide for only the best in modern comfort and relaxation.

-

About the Location +

The City of Napa and the greater Napa Valley have a history that harkens back centuries. The first know inhabitants of the area were the Native Americans, specifically the Wappo. Archeological evidence suggests that the Wappo lived in the Napa Valley for ten millennia, developing small communities of pole houses. Yet, the first settlers of European descent arrived in the early 19th century, led by the Franciscan friar, Padre José Altimira. The founder of the Mission San Francisco Solano in Sonoma, Altimira was on a mission to convert the local populace to Christianity. While some were converted by Altimira’s party, most perished from exposure to the foreign diseases that had accompanied the priests. And when Mexico finally ended the mission system in the early 1830s, most of the remaining Native Americans began to work alongside landless Mexican settlers for estate owners known as the “Californios.” The Californios introduced largescale cattle ranching in Napa Valley, as well as wheat growing. American settlers from the East Coast began to arrive toward the end of the decade, gradually turning into a flood once California became a territory of the United States. Among the first Americans to settle in the Napa Valley was George Yount, who had actually received a land grant from a Mexican official by the name of Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo. Becoming the first American horticulturalist in the area, Yount successfully built positive relations with the remaining Native Americans and was influential in local politics. Another important transplant was Nathan Combs, who had traveled west shortly before the outbreak of the Mexican-American War. He worked for Nicholas Higuera, a Californio that possessed one of the largest estates in the valley. In exchange for his servitude, Higuera eventually awarded Combs with a sizeable tract of land that he could call his own.

In 1847, Combs laid out a street grid upon which to create a magnificent city that he would call “Napa.” Combs and a fellow settler named James M. Hudspeth then surveyed the area, selecting some 600 yards of land near the Napa River to serve as the nascent community’s downtown district. The very first businesses opened within a matter of months, starting with the saloon of a former grist mill operator named Harrison Pierce. And in 1851, the newly recognized state government of California assigned Napa to serve as the seat for Napa County. But the city did not truly mature until the California Gold Rush incited a population boon that lasted right up until the beginning of the American Civil War. Struggling to survive in the countryside during the winter months, many prospective gold miners sought refuge in the accommodations that lined Main Street. As the gold mines proved worthless, many disillusioned miners turned to other industries. Most either opened a business permanently in downtown Napa, or went to work for those new business owners. Soon enough, factories, workshops, and storefronts proliferated throughout the city. Perhaps one of the greatest operation to open in downtown Napa at the time was the Sawyer Tanning Company, which became the largest tannery west of the Mississippi River! At first, the Napa River served as the primary way for local merchants and industrialists to ship their goods to other places across California. Steamships often traveled downstream to San Francisco, with the 147-foot Amelia (owned by Albert E. Hatt) the greatest of them all. Then, in 1868, the first railroad arrived, allowing for even more freight traffic to reach destinations all over the state.

The State of California formally incorporated Napa as a city during the early 1870s, signifying its status as the de-facto capital of the Napa Valley region. Napa was home to all kinds of bustling industries by the dawn of the 20th century, including the Napa Glove Factory, which was the largest plant of its kind in the western United States. Yet, another important economic development unfolded just to the north of city around the same time. Dozens of farmers began planting orchards and vineyards, giving rise to many commercial wineries. By 1889, more than 140 professional wineries were in operation, including the likes of Schramsberg, Beringer, and Inglenook. Yet, a surplus of grapes briefly toppled the market in the early 1900s, before Prohibition completely shut down the industry in 1920. Fortunately, the wineries slowly came back to life when the Roosevelt administration repealed the 18th Amendment in 1933. Some of the historic facilities were resurrected, such as Inglenook, Beaulieu Vineyards, and the Charles Krug Winery. But new wineries also debuted, as well, including Louis M. Martini’s celebrated facility. Much of the lighter industries in Napa started serving the reopened wineries, too, which reinforced the economic relationship between the city and the countryside. Today, the Napa’s Wine Country is among the most visited destinations on the planet, with dozens of world-renowned wineries available to experience. Napa itself is now one of the best resort communities in the world, and it is just over an hour away from places like San Francisco and Oakland.

-

About the Architecture +

The Napa River Inn possesses a unique architectural style that can best be described as “eclectic.” Dating to the mid-19th and early 20th centuries, historians today consider “eclecticism” to be part of a much larger movement to fuse together a variety of historical designs. Earlier in the 1800s, architects—particularly those in Europe—decided to rely upon their own loose interpretations of historical architecture whenever they attempted to replicate it. Such a practice appeared within such styles as Gothic Revival, Italianate, and Second Empire architecture. But at the height of the Gilded Age, those architects wanted to use historic architecture more literally when developing a building. A few architects went a step further by combining certain historical styles together to achieve something uniquely beautiful. And in some cases, those individuals felt inspired to add a new historical form onto a building that they were renovating—just like the Hatt Building at the time. Ultimately, the architects felt that joining such architectural forms together would give them a new avenue of expression that they otherwise did not have at the time. They also believed that they had stayed true to the earlier forms, so long as their designs perfectly replicated whatever it was they to mimicked.

In Europe, this approach first appeared as a rehash of Gothic Revival-style known as “Collegiate Gothic.” The European architects then used such a mentality to influence the unfolding philosophies of both the Beaux-Arts school of design, as well as the emerging Renaissance Revival-style. Many architects in America followed suit, the most notable of which being Richard Morris Hunt and Charles Follen McKim. The American architects who embraced “eclecticism” were at first interested in the country’s colonial architecture. Much of the desire to return to the time period was born from the revived interest in American culture brought on by the Centennial Exposition of 1876. Pride in preserving the nation’s heritage inspired the architects to perfect the design principles of their colonial forefathers in new and intriguing ways. This interest gradually splintered into other revival styles, though, like Spanish Colonial and Tudor Revival. Some Americans even infused the approach with the popular Beaux-Arts aesthetics of France, such as Hunt and McKim. Yet, the birth of Modernism in the 1920s and 1930s eventually ended the worldwide love affair with “eclecticism,” for architects throughout the West became more enchanted with the ideas of modernity, technology, and progress.