Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

Discover the Skirvin Hilton Oklahoma City, which has been an iconic Oklahoma City landmark since it opened in 1911.

The Skirvin Hilton Oklahoma City, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2008, dates back to 1911.

VIEW TIMELINEListed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places, The Skirvin Hilton Oklahoma City has a fascinating history. This spectacular holiday destination first opened when Oklahoma City was rapidly transforming into a major economic center in the early 20th century. Amid the economic renaissance, The Skirvin Hilton's founder, William Balser “Bill” Skirvin, quite literally fulfilled the role of a community builder. Originally from Michigan, Skirvin had acquired land in Oklahoma City during the Land Rush of 1889. Several years later in 1909, an investor from New York City approached Skirvin with an offer to purchase his landholdings. The investor stated his intent to develop the most extravagant hotel in Oklahoma. A shrewd entrepreneur, Skirvin turned down his offer, only to take it upon himself to build the structure. Skirvin then sought out reputed architect, Solomon A. Layton, and together, they created a blueprint for a six-story hotel with a U-shaped design. Oral tradition even stipulates that after the completion of the fifth floor, Layton persuaded Skirvin to add an addition ten levels as a means of keeping up with the thriving population of Oklahoma City. The revised hotel magnificently opened to the public on September 26, 1911, as “The Skirvin.” The Skirvin Hotel had two wings—both facing south—of 225 accommodations, as well as an interior decorated in English Gothic detail. Outside, Skirvin and Layton had used Art Deco architecture to construct the building’s exterior, creating a brilliant façade that was among the most gorgeous in all of Oklahoma City.

When he was not busy with his other enterprises, Skirvin was in the hotel greeting guests and talking to local luminaries. As a result, The Skirvin became a center for politics in the early days of Oklahoma’s statehood. Skirvin and his family moved to a five-room suite in order for Skirvin to help manage the prospering business. The Skirvin Hotel also attracted guests of all calibers from politicians to ranchers, too. Even famous bank robbers visited at one point or another. Perhaps the most notorious was Al Jennings, an ex-convict who launched his bid for governor right in the hotel’s grand lobby. The Skirvin’s popularity subsequently made it incredibly prosperous, prompting ownership to install a lavish 12-story wing for $650,000. By 1930, all three stories had been raised and the capacity was increased to 525 accommodations. Several new facilities also made their grand debut, including a roof garden and a cabaret club that cost an extra $3 million. Despite the economic disaster of the Great Depression, Skirvin remained hopeful that his wonderful grand hotel would endure for generations to come. (Skirvin himself was well protected by the vast investments in oil that he had made when he first moved to Oklahoma.) With his characteristic boldness, he declared that his team would construct a 26-story tower as a way to “expand the capabilities of his hotel.” The project began shortly thereafter. Unfortunately Skirvin fell victim to financial ruin in early 1932 and temporarily abandoned the work. The tower itself did not see completion until later that decade.

After Skirvin’s death in 1944, his three children decided to sell the gorgeous destination. They subsequently sold the entire hotel complex to Dan W. James for just a few million dollars. While its ownership changed frequently among various investors and businessmen for the next five decades, The Skirvin remained a choice destination for hundreds of guests in Oklahoma City. In fact, the hotel continued to entertain many illustrious individuals for some time thereafter, such as Elvis Presley, Frank Sinatra, Jimmy Hoffa, Roger Staubach, Mikhail Baryshnikov, and Bob Hope. The Skirvin Hotel also hosted former U.S. Presidents, including Harry S. Truman and Dwight D. Eisenhower. Nevertheless, the hotel’s popularity entered a steady decline toward the end of the century. The diminishing interest with the business ultimately forced it to close its doors for good in 1988. After sitting dormant for the next two decades, contractors began preparing The Skirvin for a long-awaited restoration. The craftsmen specifically focused on rehabilitating the entire interior, within which they installed historically accurate windows and new guest elevators. After more than $50 million in renovations, the building reopened as “The Skirvin Hilton Oklahoma City” to great acclaim in 2007. A member of Historic Hotels of America since 2008, The Skirvin Hilton Oklahoma City is now once again among the best places to stay in all of Oklahoma.

-

About the Location +

Oklahoma City is one of the most exciting places to visit in the entire South. Not only is Oklahoma City the state capital of Oklahoma, but it is also its largest, with a population of around 655,000. This fantastic metropolis first came into existence during the waning days of the Old American West. Most of the area’s original Euro-American inhabitants arrived in the region amid what many historians have since referred to as “The Land Run” or the “Run of ’89.” Between the late 1880s and early 1900s, some 10,000 settlers arrived in Oklahoma’s “unassigned land,” the territory in which the federal government had not assigned to any Native Americans. (Oklahoma has existed for many years prior as “Indian Territory,” a place where the federal government had controversially relocated various Native American tribes.) The greatest wave of settlement transpired in 1889, though, when nearly half the number of Oklahoma City’s original pioneers arrived in the area. While the initial wave of pioneers were frontiersmen and cattle ranchers, more ordinary settlers—such as merchants and laborers—began congregating upon rudimentary plots of land within the unassigned lands. Most began settling near a train stop created by the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway, called the “Oklahoma Station.” In just a matter of months, the settlers had gradually formed their disparate plots of land together to form an actual community around the isolated depot. Due to mounting pressure to legalize the land rush, Congress and President Benjamin Harrison formally organized the region into seven counties and approved the chartering of “Oklahoma City” in the spring of 1890. Despite Oklahoma City’s growth, the nearby town of Guthrie became the first capital. A rivalry between the two communities then existed for the next two decades, until a referendum permanently established Oklahoma City as the state capital in 1910. (Oklahoma had just become a state itself only three years prior.)

The population of Oklahoma City continued to swell, reaching well over 64,000 people on the eve of World War I. Its growth had largely been spurred by a spate of commercial real estate development, driven by countless entrepreneurs who coordinated closely with both the city’s Chamber of Commerce and the state government. Many prominent industries debuted in the community during the early 20th century, including dozens of heavy manufacturing operations like the Oklahoma City Ford Motor Company Assembly Plant. Yet perhaps the greatest to debut at the time was its lucrative meatpacking trade. Its proximity to hundreds of cattle ranches rendered the city a natural fit to distribute livestock and meat throughout the southern United States, giving rise to many warehouses and food processing plants. (Local farmers also transported various crops into Oklahoma City, too, such as cotton, wheat, and corn. Nonetheless, the distribution of livestock remained the primary staple that local agriculturalists sent into the community.) Stockyards in Oklahoma City became a regular site, supplanting the ones in Chicago and Omaha in both size and prosperity. And the discovery of oil just beyond the city limits in the 1920s transformed the community into one of the most industrious places for the domestic production of petroleum and natural gas products. The greater Oklahoma City area even had around 1,400 derricks in operation at the height of the Roaring Twenties. People continued to flock into the area over the next several decades, as well, with the city’s population increasing to an astonishing 300,000 by the 1950s. Today, Oklahoma City is still one of the most important communities in the South. It remains the home to many prominent industries and hosts such renowned cultural attractions like the Oklahoma City Museum of Art, the Myriad Botanical Gardens, Bricktown, and the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum.

-

About the Architecture +

Designed together by William Balser “Bill” Skirvin and Solomon A. Layton, The Skirvin Hilton Oklahoma City is a wonderful example of Art Deco design aesthetics. Art Deco itself is still one of the most famous architectural styles in the world. The form originally emerged from a desire from architects to break with past precedents to find architectural inspiration from historical examples. Instead, professionals within the field aspired to forge their own design principles. More importantly, they hoped that their ideas would better reflect the technological advances of the modern age. As such, historians today often consider Art Deco to be a part of the much wider proliferation of cultural “Modernism” that first appeared at the dawn of the 20th century. Art Deco as a style first became popular in 1922, when Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen submitted the first blueprints to feature the form for contest to develop the headquarters of the Chicago Tribune. While his concepts did not win over the judges, they were widely publicized, nonetheless. Architects in both North America and Europe soon raced to copy his format in their own unique ways, giving birth to modern Art Deco architecture. The international embrace of Art Deco had risen so quickly that it was the central theme to the renowned Exposition des Art Decoratifs in Paris a few years later. Architects the world over fell in love with Art Deco’s sleek, linear appearance, defined by a series of sharp setbacks. They also adored its geometric decorations that featured such motifs as chevrons and zigzags. But in spite of the deep admiration people felt toward Art Deco, interest in the style gradually dissipated throughout the mid-20th century. Many examples of Art Deco architecture survive today, with some of the best located in such places as New York City, Chicago, and Miami Beach.

Guest Historian Series

Read Guest Historian SeriesNobody Asked Me, But… No.203 & 204;

Hotel History: The Skirvin Hotel (1917), Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

By Stanley Turkel, CMHS

The Skirvin Hilton Hotel is Oklahoma City’s oldest hotel. It was built by William Balser Skirvin, a native of Michigan who made his fortune in Texas land development and oil. In 1906, Skirvin and his family (including his daughter Pearl who would later become Perle Mesta, ambassador to Luxemborg and a famous Washington hostess) moved to Oklahoma City. Skirvin hired Solomon Andrew Layton, an American architect who designed over 100 public buildings in the Oklahoma City area including the Oklahoma State Capitol. Twenty-two of Layton’s buildings are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Skirvin and Layton made the hotel as self-sufficient as possible. Skirvin installed a proprietary gas pipeline to the building, dug three wells for water supply, built an electric generating plant and operated an in-house laundry and cooling system.

On September 26, 1911, the ornate Skirvin Hotel was opened for public inspection. Visitors attracted to the 10-story building found two exterior wings, each facing south, and a rounded bay between the wings running the height of the structure. The façade was red brick laid in a Flemish bond pattern, the lower level was faced with limestone, and had two covered entryways. Inside, visitors were greeted with a spacious lobby decorated in English Gothic detail. On the west end of the first floor were the Skirvin Drugstore and other retail shops. On the other wing, customers found the Skirvin Café with a stage for musicians. The café was complemented by the Grill Room in the basement and the Tea Room on the mezzanine.

Entering one of the two electric elevators, guests rose to the upper floors where they found 225 guestrooms and suites. Each room had a private bath, was decorated with velvet carpets and hardwood furniture, and had a telephone connected to the Pioneer Telephone Company lines through a large switchboard located behind the front desk.

Skirvin continued to give the hotel much of his attention, despite the daily presence of his first general manager, Frederick Scherubel. Most days, when he was not attending to his oil interests, Skirvin could be found in the lobby greeting guests or talking with businessmen and politicians. He donated a room to the Republican Party, and welcomed Democrats, so the hotel became a center for politics during the early years of statehood. To be close to his “225-room hobby,” Skirvin moved his family to a five-room suite on the ninth floor. In addition to his three children, the Skirvin household consisted of the kids’ menagerie of dogs, raccoons, hawks, and other animals, which they kept on the roof.

During the next ten years, the guest register of the Skirvin Hotel reflected the frontier character of the young, bustling state. Guests included cigar-chomping politicians, free-wheeling ranchers, blanketed Indians from the state’s 70 tribes, oil-rich millionaires, mud-covered drillers, and even bank robbers such as the notorious Al Jennings, the ex-convict who launched his bid for governor from the lobby. William Skirvin, always impeccably dressed in his well-pressed suit, welcomed all with open arms.

By 1923, the hotel’s success and the continued growth of Oklahoma City convinced Skirvin that expansion was justified. Again, the oilman went to the architect Solomon Layton, who developed plans to add another wing and bay to the east, replacing the one-story garage. In addition, plans called for remodeling all existing rooms, the first of many refurbishings which would improve the hotel each decade thereafter. By 1926, with the investment of $650,000, the hotel had a new wing of 12 stories and two wings with 10 stories each.

In March 1928, as another prosperous era was overtaking Oklahoma City, Skirvin announced plans to raise all wings to 14 stories and to initiate an extensive remodeling of the entire hotel. One year and three months after the first well in the world-famous Oklahoma City oil field was discovered, Skirvin let the first contracts for the renovation. By April 1930, the entire building had been raised to 14 floors with 525 guestrooms, a roof garden, a cabaret club and the old café converted into a modern coffee shop. On the ground level, the lobby was doubled in size with specially-designed Gothic lanterns costing $1,000 each suspended from the ceiling, and hand-carved English fumed oak was added to the walls and doors. Skirvin’s most popular addition proved to be the 14th floor rooftop Venetian Room and Restaurant which was decorated with Italian plaster, a parquet hardwood floor, and more than 100 casement windows for flow-through ventilation. Adjoining it on the east, was a new kitchen, furnished with the most modern appliances.

In the west wing, and connected to the restaurant by a foyer, was the Venetian Room, a supper club featuring live music and dancing. Paneled with American walnut and draped with embroidered mohair, brocatelle and damash, the club was decorated with murals depicting Venetian scenes. The floor was specially designed for dancing with alternate blocks of red and white oak polished to a high sheen.

The opening performer was Hal Pratt and his Fourteen Rhythm Kings featuring Hilda Olsen and the Ruth Laird Rockets. Subsequent Venetian Room performers were Zez Confrey, Ted Weems, Ted Fiorito, Jimmy Joy, Johnny Johnson, Charlie Straight, the Seven Aces, the Ligon Smith Band and Peppino and Rhoda, famous ballroom dancers.

Oklahoma City was buffeted by the mounting economic depression which began in December of 1929. With his typical boldness, Skirvin announced that he would expand the hotel by building an annex across Broadway. In March of 1931, crews broke ground for the planned 26-level Skirvin Tower, and work continued until January of 1932, when suddenly Skirvin’s resources crumbled. With only 14 floors of the superstructure completed, Skirvin was forced to temporarily abandon the project, a victim of the spreading financial depression.

Early in 1934, Skirvin resumed work on the Tower, but it was not competed until 1938, and even then only a few of the floors were ready for occupants. Described as a “luxury apartment-hotel,” the Tower was linked to the hotel by a tunnel and many of the service employees worked in both buildings. Later owners would finish the interior and operate the Tower as a hotel until 1971, when it was completely remodeled into a glass-enclosed office building. When William Skirvin passed away in 1944, his three children decided to sell the properties.

In May of 1945, only weeks after Germany’s surrender, the hotel and tower were sold for $3 million to Dan W. James, owner of the Black Hotel, another of the City’s six luxury hotels. James brought considerable hotel management skills to the Skirvin, for he had worked in hotels from Louisiana and Arkansas to Texas and Oklahoma. In 1931, he came to Oklahoma City and bought the Black Hotel. When he assumed control of the Skirvin properties, he faced a formidable task, as high traffic, scarce replacement materials, and absent employees had taken a heavy toll during World War II.

To resurrect the quality and elegance of Skirvin, James embarked on a 10-year modernization program. He installed air conditioning for the entire building; he replaced the original entryway canopies with a wrap-around awning; he added a drive-in registry and a parking garage to the north side; and he redecorated all of the meeting rooms on the east side of the mezzanine. James invested even more in the Tower, where he remodeled the Persian Room, created the Tower Club, and refinished many of the luxury apartments and suites. James realized that a luxury hotel could not succeed in the 1940s without offering a wide range of services to the public. He made every effort to provide room service, in-by-nine-out-by-five guest laundry, a stenographer and notary, a beauty shop, a barber shop, and a house physician.

James instituted several programs to insure good employee relations and maximum effort. He created an 8-page in-house magazine, Inn-Side Stuff, which carried news about employees, contests for efficient service, and information about other divisions of the hotel. James also introduced employee benefit programs such as company-paid insurance policies for longtime workers and annual Christmas dinners for all staff members and their families.

Such policies made the Skirvin one of the most successful hotels in the Southwest, an important role in a city, which was third only to New York and Chicago in the number of conventions attracted each year. This status was enhanced during the post-war years by the presidential visits of Harry Truman and by Dwight D. Eisenhower. Both events helped establish the Skirvin as the queen of hotels in Oklahoma City.

Hotel owner Dan W. James, like Bill Skirvin before him, did not rest on past accomplishments. In 1959, a swimming pool was added to the north side of the hotel, and one year later he built the Four Seasons Lounge next to the pool. Despite such attempts to modernize his enterprises, James and other hotel operators were confronting the decline of the central city. Beginning in 1959, new suburban shopping malls were built every few years, drawing shoppers away from downtown. Another factor in the central city’s decline was the new age of motor car transportation, which shifted emphasis from railroads and streetcars to busses and automobiles. City streets, designed for pedestrian traffic and only limited motor use, were too congested for heavy traffic, while limited space impeded convenient parking.

In 1963, just as the problems confronting downtown Oklahoma City were mounting, James announced that he had sold the Skirvin to a group of investors from Chicago. Although this partnership added a $250,000 banquet room to the hotel and made grand plans for the development of both the Skirvin Hotel and Tower, they sold the destinations to H.T. Griffin in 1968.

Griffin, who planned to build the proposed Liberty Tower just to the south of the hotel, unveiled a two-year plan intended to rejuvenate the Skirvin and reverse the exodus from downtown Oklahoma City. With an investment of $2.5 million, he redecorated the Sun Suite, added a new restaurant, replaced all the window sashes with bronze-colored frames, replaced all the furniture, added color television sets to each room, and remodeled the lobby, kitchen and coffee shop.

Despite this massive investment, Griffin encountered difficulties. Urban renewal construction was active during the late 1960s, further congesting traffic and discouraging movement downtown. Occupancy rates declined, reaching a nadir of only 32 percent in 1969, a period when an occupancy of 70 percent was necessary to pay operating expenses and outstanding bank loans. In 1968, the hotel made a small profit, but in 1969 and again in 1971 the Skirvin suffered losses. Combined with heavy investment in Liberty Tower, the negative cash flow forced the Griffin into bankruptcy in late 1971.

At this low point in its celebrated history, the Skirvin was placed in the hands of a trustee, Stanton L. Young, who borrowed money for operations and searched for a way to pay off debts and return the hotel to its former grandeur. One year later, Young negotiated to sell the Skirvin Hotel to CLE Corporation, a Texas firm that already owned and managed a chain of hotels across the nation. Purchase price was approximately $2 million.

In late 1972, the new owner announced that the name of the hotel would be changed to “Skirvin Plaza Hotel” and pledged to invest $2.3 million in a general remodeling campaign – a figure which would increase to $8 million by 1974. Much of the work was exterior facelifting, such as repointing mortar, cleaning bricks, and replacing old awnings. Every guest room was gutted and redecorated in one of eight different styles and all new plumbing and electrical wiring was installed.

Suffering from sagging occupancy despite their investments, CLE Corporation in 1977 sold the Skirvin to the Businessman’s Assurance Company. The City’s other fine hotels, such as Huckins, Biltmore, Tower and Black, already had been abandoned, demolished, or converted to office space.

The life of the Skirvin, hanging in the balance for the past 16 years, received a new chance in 1979 when a small group of investors recognized the latent potential of the hotel. With a faith reminiscent of Bill Skirvin, the new investors purchased the hotel for a reported $5.6 million. With the combined resources and talent of investors Ron Burks, Bill Jennings, John Kilpatrick, Jr., Bob Lammerts, Jerry Richardson, Dub Ross and Joe Dann Trigg, the Skirvin Plaza Investors approached their new challenge aggressively.

With a $1 million commitment, the investors undertook an extensive remodeling campaign. In the lobby, workers removed an added staircase in order to regain the openness of the original design. Then, while demolishing other additions, workers found an original wooden archway, which served as a pattern for the design of other arches and wood trim. Above the refurbished walls, ceiling murals were recreated and massive chandeliers imported from Czechoslovakia were installed. The Skirvin, after suffering two decades of decline, was to get another chance.

In 1980, the future of the Skirvin seemed assured. The interior renovation was nearly completed and events were unfolding around the Skirvin that would attract new visitors. Urban renewal, which had slowed during the mid-1970s, gained new momentum when a developer from Dallas began work on the Galleria, the long-promised retail and office complex just a block west and south of the Skirvin.

Another remarkable new development downtown was the preservation of several of the City’s foremost historic buildings. Spurred by mounting prosperity, tax incentives, and the growing demand for office space, investors purchased and renovated structures such as the Colcord Hotel, the Harbour-Longmire, the Black Hotel, Montgomery Ward, and the Oil and Gas Building. This facelifting injected new life into the central city.

The significance of the Skirvin Hotel in the history of Oklahoma was officially recognized late in 1980 when two plaques were unveiled by Governor George Nigh. One plaque designated the inclusion of the hotel on the National Register of Historic Places; the other marked a similar honor from the Oklahoma City Historic Preservation and Landmark Commission.

Nevertheless, the Skirvin skidded into bankruptcy and closed down in 1988 and sat empty until 2007 when it was acquired by Marcus Hotels and Resorts who undertook a $55 million renovation. On its 100th birthday, the hotel reopened as the Skirvin Hilton Hotel and has earned a AAA Four Diamond rating every year since.

“We are delighted to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the oldest existing hotel in the state of Oklahoma. The Skirvin Hilton is a grand hotel in the tradition of historic hotels, and was our fourth historic restoration,” said Bill Otto, president of Marcus Hotels & Resorts. “While carefully retaining its historic details, we completely renovated the property and introduced successful restaurant concepts, including the Park Avenue Grill and Red Piano Bar. We are proud to be a part of this celebratory event – and proud to continue to deliver exceptional service to our Oklahoma City guests.”

The project leveraged Marcus Hotels’ 50 years of experience in restoring landmark hotels. Martin Van Der Laan, general manager said, “The Skirvin Hilton has been considered the city’s crown jewel through the turbulent years and rebirth of downtown Oklahoma City in 2006. Today the hotel serves as a chronicler of the city’s history and remains an important piece of the city’s past and future”.

The Skirvin Hilton Hotel is a member of the Historic Hotels of America, the official program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

*For a more detailed history of the Skirvin Hilton Hotel, see the well-illustrated and well-written Skirvin by Jack Money and Steve Lackmeyer, Full Circle Press: Oklahoma City, 2007.

*****

About Stanley Turkel, CMHS

Stanley Turkel is a recognized consultant in the hotel industry. He operates his hotel consulting practice serving as an expert witness in hotel-related cases and providing asset management an and hotel franchising consultation. Prior to forming his hotel consulting firm, Turkel was the Product Line Manager for worldwide Hotel/Motel Operations at the International Telephone & Telegraph Co. overseeing the Sheraton Corporation of America. Before joining IT&T, he was the Resident Manager of the Americana Hotel (1842 Rooms), General Manager of the Drake Hotel (680 Rooms) and General Manager of the Summit Hotel (762 Rooms), all in New York City. He serves as a Friend of the Tisch Center and lectures at the NYU Tisch Center for Hospitality and Tourism. He is certified as a Master Hotel Supplier Emeritus by the Educational Institute of the American Hotel and Lodging Association. He served for eleven years as Chairman of the Board of the Trustees of the City Club of New York and is now the Honorary Chairman.

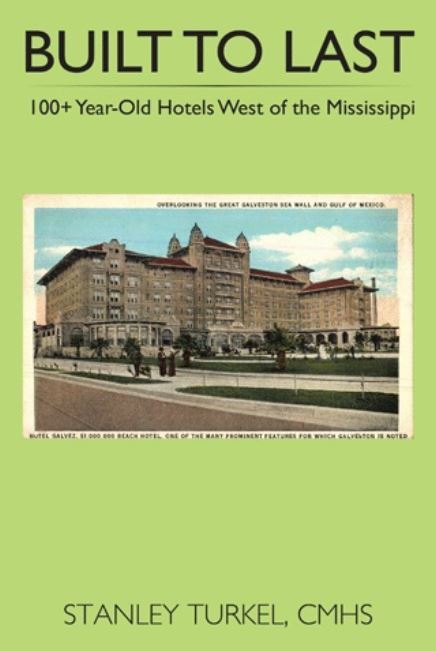

Stanley Turkel is one of the most widely-published authors in the hospitality field. More than 275 articles on various hotel subjects have been posted in hotel magazines and on the Hotel-Online, Blue MauMau, Hotel News Resource and eTurboNews websites. Two of his hotel books have been promoted, distributed and sold by the American Hotel & Lodging Educational Institute (Great American Hoteliers: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry and Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels East of the Mississippi). A third hotel book (Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels in New York) was called "passionate and informative" by the New York Times. Executive Vice President of Historic Hotels of America, Lawrence Horwitz, has even praised one book, Great American Hoteliers Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry:

- “If you have ever been in a hotel, as a guest, attended a conference, enjoyed a romantic dinner, celebrated a special occasion, or worked as a hotelier in the front or back of the house, Great American Hoteliers, Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry is a must read book. This book is recommended for any business person, entrepreneur, student, or aspiring hotelier. This book is an excellent history book with insights into seventeen of the great innovators and visionaries of the hotel industry and their inspirational stories.”

Turkel was designated as the “2014 Historian of the Year by Historic Hotels of America,” the official program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. This award is presented to an individual for making a unique contribution in the research and presentation of history and whose work has encouraged a wide discussion, greater understanding and enthusiasm for American History.

Works published by Stanley Turkel include:

- Heroes of the American Reconstruction (2005)

- Great American Hoteliers: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2009)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels in New York (2011)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels East of the Mississippi (2013)

- Hotel Mavens: Lucius M. Boomer, George C. Boldt and Oscar of the Waldorf (2014)

- Great American Hoteliers Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2016)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels West of the Mississippi (2017)

- Hotel Mavens Volume 2: Henry Morrison Flagler, Henry Bradley Plant, Carl Graham Fisher (2018)

- Great American Hotel Architects Volume 1 (2019)

- Hotel Mavens Volume 3: Bob and Larry Tisch, Curt Strand, Ralph Hitz, Cesar Ritz, Raymond Orteig (2020)

Most of these books can be ordered from AuthorHouse—(except Heroes of the American Reconstruction, which can be ordered from McFarland)—by visiting www.stanleyturkel.com, or by clicking on the book’s title.